Decoding the science of continuous glucose monitoring

Are CGMs an essential key to metabolic health and personalised nutrition, or a big fat waste of time and money?

Toward the end of my recent conversation with Jason Olbourne, my host asked me to share my top health tips. I stressed the importance of going outdoors to breathe fresh air and get some sensible sunshine exposure, drinking pure fluoride-free water, eating real food rather than ultraprocessed goop, moving your body, and, if and when you do get sick, recognising your symptoms as your body's attempt to restore health, rather than suppressing these symptoms with medications.

You'll notice that I did not include 'wearing a continuous glucose monitor' in that prescription for health. Unlike Casey Means, the as-yet-unconfirmed nominee for US Surgeon General, whose major claim to fame is having co-founded the glucose monitoring company Levels1, I do not endorse the use of continuous glucose monitors by people who do not have insulin-dependent diabetes, because there is no evidence of benefit in this population and some possibility of harm.

Before I walk you through the evidence for both those statements, let's cover the basics.

What is a continuous glucose monitor, and what is it actually monitoring?

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are devices that provide regular estimates of glucose concentration, and keep track of glucose levels over time. CGMs consist of three components:

A sensor, which periodically estimates the concentration of glucose in interstitial fluid, the fluid between your cells. Disposable sensors are inserted just under the skin (either on the back of the arm or the abdomen) using an applicator which pierces the skin, and are then held in place by a sticky patch. They must be replaced regularly - usually every one to two weeks. Implantable sensors are small pellets that are inserted under the skin of the upper arm by a healthcare provider; they last for several months.

A wireless transmitter, which sends the glucose data to a device (e.g. a mobile phone app) for viewing.

A smartphone app, receiver or insulin pump, which displays the glucose data and, in the case of the pump, can automatically adjust your insulin dose, based on your current glucose level.

CGMs are a boon to insulin-dependent diabetics, who otherwise have to endure multiple daily - and often painful - fingersticks to obtain capillary blood samples that are then read by their home blood glucose meter, in order to calculate their insulin dosages.

Note that CGMs monitor the concentration of glucose in interstitial fluid, not in the blood. Glucose absorbed from a meal enters the bloodstream, and then disperses into interstitial fluid. Consequently, there's an average lag time of eight to ten minutes between blood glucose and interstitial fluid glucose levels, which means that fingerstick and CGM readings are not directly comparable. Diabetics are instructed to regularly calibrate their CGM against their blood glucose meter readings, and to verify concerningly high or low CGM readings with a fingerstick check.

So far, so good. There's a strong argument for the use of CGMs by insulin-dependent diabetics (that is, all type 1 diabetics, and the type 2s who inject insulin), and this patient population has access both to diabetes educators who can teach them how to use the devices properly, and to blood glucose meters to calibrate them.

But what happens when companies like Zoe, and Casey Means' Levels, market the use of CGMs to the non-diabetic general public, on the promise that blow-by-blow information on how their glucose level is responding to various diet and lifestyle factors will help them 'personalise their nutrition program', or 'unlock their metabolic health?' The vast majority of non-diabetics do not have access to home blood glucose meters for calibration and cross-checking of their CGM. And users are reliant on the interpretation of their data provided by the Levels and Zoe apps. What could possibly go wrong? Plenty, as the research literature shows.

Same meal, different CGM response

The rationale behind using a CGM to construct personalised dietary advice, is that it can identify particular foods that cause 'glucose excursions'. A glucose excursion is not a fun day-trip for sugarholics, but an abnormally high post-meal spike in blood glucose level. These glucose excursions have been shown to cause acute inflammatory reactions, oxidative stress, dysfunction of the inner lining of the arteries (contributing to the development of atherosclerotic plaque) and, over the long term, to insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. If people exclude foods that induce these spikes, they can maintain healthier blood glucose levels and stave off metabolic dysfunction. Or so the theory goes.

However, there's a small problem with this theory: according to research conducted by the somewhat legendary Kevin Hall, the exact same meal can cause wildly different CGM responses when eaten by the same person, on different days. Oopsie.

I've discussed several of Kevin Halls' elegantly-designed, meticulously conducted experiments on human metabolism before, in Obesity: Bad to the Brain, Ultraprocessed foods make you overeat – even when you don’t want to – and cause weight gain, and Ketogenic diets: Part 3 – Weight loss. Suffice it to say, when I see Hall's name on a study's author list, I know it's going to be high-quality work.

And Hall's CGM study did not disappoint. (In an obvious dig at Zoe's 'precision nutrition' tagline, the study was titled 'Imprecision nutrition? Intraindividual variability of glucose responses to duplicate presented meals in adults without diabetes'. Researchers are allowed to have a little fun, too.)

Hall tested two different CGMs (Abbott Freestyle Libre Pro and Dexcom G4 Platinum) on 30 non-diabetic participants. Participants resided at the NIH Clinical Center Metabolic Clinical Research Unit for four weeks each, wearing at least one type of CGM throughout their stays. During each of these four-week experimental periods, participants were fed three meals per day on an ad libitum (eat as much as you want) basis, from seven-day rotating menus conforming to four distinct dietary patterns: a minimally processed plant-based, low-fat diet; a very low carbohydrate ketogenic diet; a diet based on ultraprocessed foods; and a diet matched on macronutrients to the ultraprocessed diet, but comprising unprocessed foods.

Some participants wore both the Freestyle Libre Pro and the Dexcom G4 Platinum CGMs (i.e. one CGM on each arm) during the ultraprocessed vs unprocessed diet experiment, while all participants wore the Dexcom CGM during the plant-based low-fat vs ketogenic diet experiment. Each dietary pattern was followed for two weeks, and because of the seven-day rotating menu, participants ate identical meals at the same time of day, on two separate occasions, one week apart. In all, 1189 CGM responses to duplicate meals were captured. (Data from the ketogenic diet period were excluded because CGM responses to these meals were minimal.)

When Hall and his co-authors analysed the data, they found that not only did each participant's CGM responses to different meals vary widely, their CGM responses to the exact same meal, served on two separate occasions at the same time of day but one week apart, also varied widely. And in fact, the glycaemic response variability to duplicate meals was of similar magnitude to the variability in glycaemic responses to different meals.

To rule out various factors that might have influenced this variability in glycaemic response, the researchers conducted analyses using only CGM data from duplicate meals where energy intake was within 100 kcal between meals; and where participants' between-meal snack intake was <200 kcal on both duplicate meal days. Neither of these analyses yielded significantly different results from the main findings.

Put simply, CGMs do not provide reliable guidance on which meals cause glucose excursions in non-diabetic individuals, and should not be used to personalise one's diet for improved metabolic health. Especially when...

Different CGMs give different responses to the exact same meal eaten by the same person

In a previously-published paper, Hall documented the results of the study comparing the CGM responses of the Abbott Freestyle Libre Pro and Dexcom G4 Platinum, when worn simultaneously by the same participants. The Dexcom CGM estimated participants' average glucose significantly higher than the Abbott device (Dexcom 93.4 ± 0.12 mg/dL vs Abbott 80.5 ± 0.12 mg/dL; P < 0.0001; that's 5.2 mmol/L vs 4.5 mmol/L). This discrepancy is substantial - essentially, it's the difference between an individual with a perfectly healthy glucose level, and one who is on the slippery slope toward diabetes.

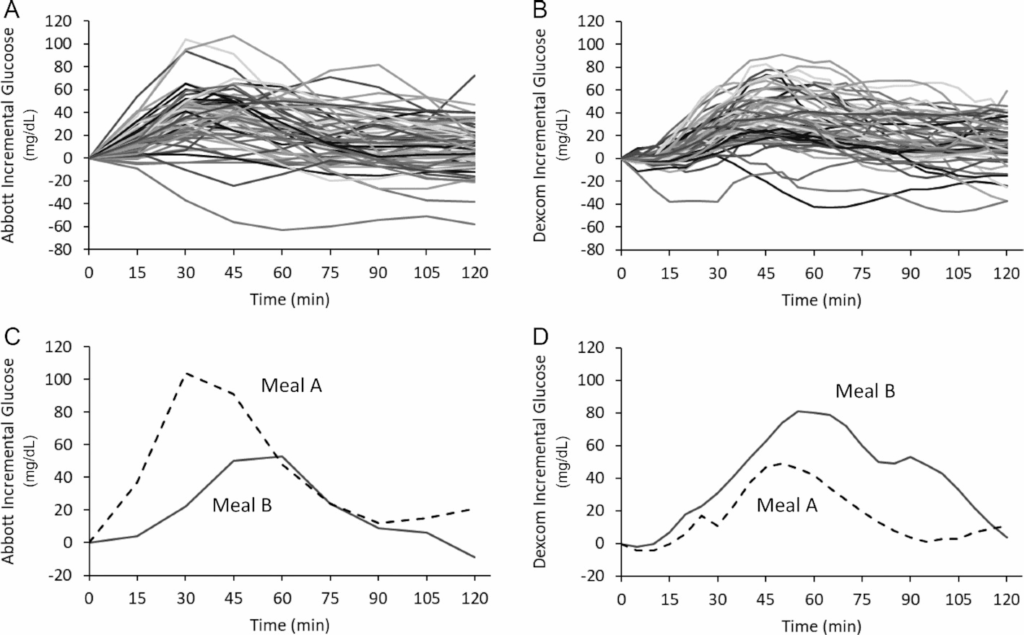

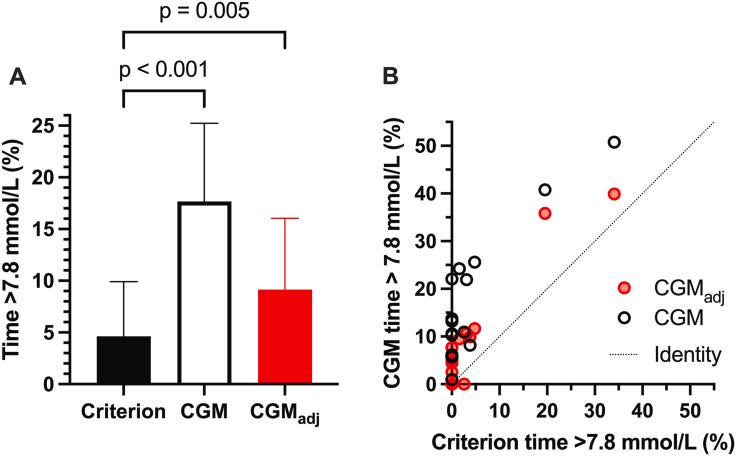

Likewise, the two devices had discordant responses to the exact same meals, as clearly shown in the figure below. Notice how high the glucose excursion in response to Meal A is, according to the Abbott CGM, while the Dexcom device does not register any glucose excursion in response to this meal:

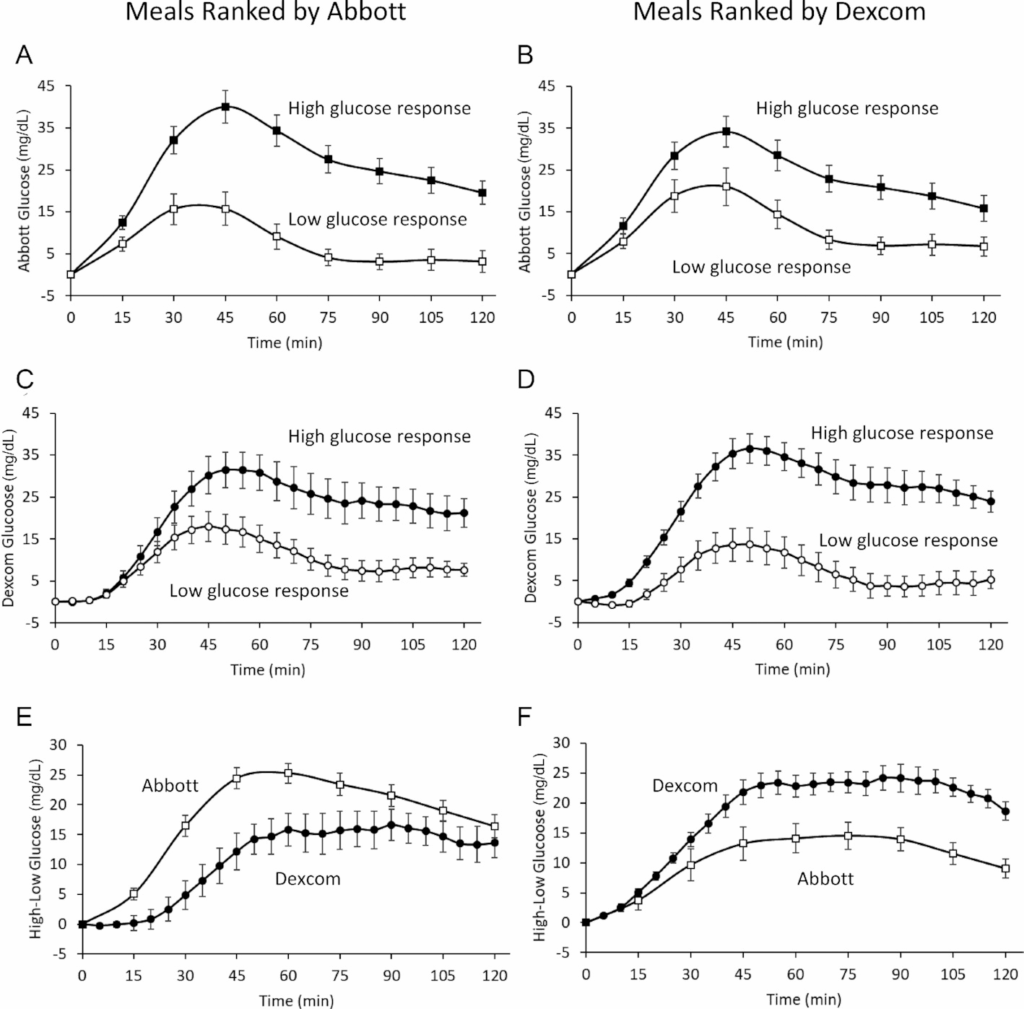

Moreover, there was a significant discrepancy between the two devices in how they ranked glucose responses to different meals. The Abbott CGM measured a 17.9 ± 1.1 mg/dL (1.0 ± .1 mmol) difference in mean incremental glucose between the meals with the highest glycaemic response and those with the lowest; when the same meals were ranked by the Dexcom system, the difference in the mean incremental glucose between the top and bottom half of ranked meals was far less:10.7 ± 1.6 mg/dL (0.6 ± 0.1 mmol/L).

Great. So if you wear one brand of CGM on one arm, and a different brand on the other arm, you'll get completely different feedback from each device on how your body is responding to your meals. Good luck formulating your 'precision nutrition' program for optimising your metabolic health, with that degree of slop in the data.

CGMs overestimate glycaemic response to foods, compared to capillary sampling

As mentioned previously, insulin-dependent diabetics are instructed to calibrate their CGM readings against the readings obtained by their blood glucose meter, from capillary sampling (fingerprick testing). Fingertip capillary sampling is also considered the gold-standard method of measuring glycaemic responses to foods - in other words, the rise in blood glucose level that occurs in response to eating a particular food.

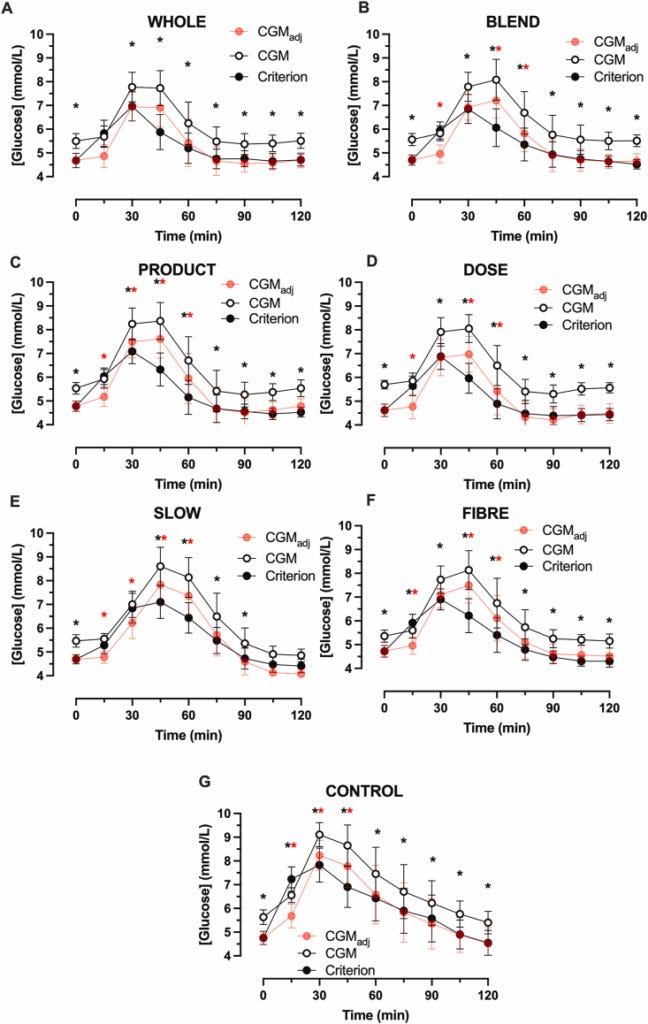

But what happens when these two measures of glucose response are compared in non-diabetics? To find out, researchers from the University of Bath in the UK recruited 15 healthy subjects to test their glycaemic response, as measured by both CGM and capillary sampling, to 50 g of carbohydrate consumed either as glucose, whole fruit, blended fruit, a commercially available fruit smoothie, a commercially available fruit smoothie ingested over 30 ± 4 minutes, or a commercially available fruit smoothie with 5 g of inulin (a prebiotic fibre); and to 30 g carbohydrate as commercially available fruit smoothie. Each oral carbohydrate challenge was conducted in a separate laboratory visit, with at least 48 hours between challenges.

The researchers found that CGM-estimated fasting glucose concentrations were 0.9 ± 0.6 mmol/L (16.2 ± 10.8 mg/dl) higher than capillary estimates, while postprandial (i.e. after-meal) glucose concentrations were 0.9 ± 0.5 mmol/L (16.2 ± 9.0 mg/dl) higher when measured by CGM than by capillary sampling.

CGM also overestimated time out of range (i.e. the amount of time participants' blood glucose levels exceeded the desirable level of 7.8 mmol/L [140 mg/d]) by roughly four-fold, or roughly two-fold after adjustment for baseline differences in fasting blood glucose between CGM and capillary sampling measurements.

And finally, the CGM ranked the various carbohydrate challenges in a different order than capillary sampling. According to capillary sampling, the rank order of glycaemic responses to each of the carbohydrate challenges was, from highest response to lowest response, CONTROL > SLOW > BLEND > PRODUCT > WHOLE > FIBER > DOSE, while the CGM rank order was CONTROL > SLOW > PRODUCT > FIBER > BLEND > DOSE > WHOLE.

OK, so CGMs report inconsistent glycaemic responses to the same meal eaten on different occasions, different brands of CGM yield discordant responses to the same meal, and CGMs are unreliable compared to the gold standard of measurement of glycaemic responses to food, capillary sampling. But if you're still determined to waste your money on using one, are there any actual harms that you should consider? Yes, absolutely.

Potential harms of CGMs

If you rely on a CGM to guide your food choices, you are extremely likely to be persuaded to cut perfectly healthy foods out of your diet, by the mistaken belief that they are causing harmful glucose excursions. Moreover, you'll be influenced to replace these nutritious and health-promoting foods with unhealthy foods or unhealthy dietary patterns (such as very low carbohydrate animal food-based diets), because these foods or patterns yield a 'flat' glucose response.

The authors of the study comparing CGMs to capillary sampling in non-diabetic people were well aware of this hazard:

"Companies now encourage people to use CGM to guide lifestyle choices with a target of maintaining blood glucose in a specific range, and these devices can be bought 'over-the-counter' [8,9]. These data suggest that CGM may overestimate the time that healthy people spend outside this range and misrepresent the relative glycemic response of certain beverages, thereby misleading people about nutritional strategies to lower postprandial glycemia."

And so were Kevin Hall and his team:

"Misclassifying meals or foods as 'bad' or 'good' in terms of their CGM responses may affect overall eating behaviors with potentially deleterious consequences. For example, if diet recommendations are based on imprecise CGM measures that disregard other aspects of optimal nutrition, then individuals may make poor dietary choices to achieve potentially illusory glycemic benefits."

Edit:

The following comment from Red_Pill_Aussie was so on-point, I wanted to bring all readers’ attention to it:

I can also tell you from professional experience, that people with a history of restrictive eating disorders should not be within cooee of a CGM (unless of course they have insulin-dependent diabetes). Talk about adding fuel to the fire!

The risk:benefit calculation for the use of CGMs in people who do not have diabetes is pretty clear: there's no benefit, and plenty of potential risk. But what about the edge cases - people with prediabetes?

Accuracy of CGM in diabetic, prediabetic and nondiabetic individuals

In a study of 581 Spanish adults, of whom 12 per cent had previously been diagnosed with diabetes and 21 per cent fulfilled the criteria for prediabetes (haemoglobin A1C range of 5.7–6.4% or a fasting plasma glucose range of 100–125 mg/dL [5.6-6.9 mmol/L]), inter-day reproducibility of CGM measurements was greatest in participants with diabetes, intermediate in those with prediabetes, and lowest in normoglycaemic participants.

Inter-day reproducibility of CGM data was also better in older than in younger participants.

However, even in the best use-case for CGM - diabetic individuals - inter-day reproducibility of CGM measurements was still only ranked as 'fair' (compared to 'poor' for every other category of participants, including the elderly nondiabetics). And, according to the authors, rather than the greater inter-day reproducibility proving that CGM is more accurate in diabetics, it "might indicate that these subjects have lost functional adaptational capacity compared to, for example, normoglycemic subjects," or that their medication and/or prescribed dietary regimes are maintaining more stable CGM readings. Hmmmm.

My conclusion, after reviewing these studies, is that CGM:

Should not be used at all by people who do not have diabetes; and

Should be used very cautiously by people who have diabetes or prediabetes, with the proviso that its reliability is very low and it should not be used to construct personalised nutrition plans without a) repeated measurements of CGM responses to individual foods in a variety of contexts (e.g. different meal composition, order of eating, time of day of consumption, preceding physical activity, sleep adequacy) and b) cross-checking against fingerprick blood glucose measurements.

People who use CGMs should also be aware that certain medications and supplements can affect the accuracy of certain CGM devices, including:

Acetaminophen/paracetamol (Tylenol® or Panadol®);

Hydroxyurea, a medication that is used to treat sickle cell anaemia; and

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid).

Final thoughts

Just as the use of calculators, spell-checkers, GPS navigation systems and large language models (LLMs like ChatGPT, Gemini and Grok) has rendered people increasingly incapable of performing basic intellectual functions, the burgeoning use of 'wearables' including CGMs, is making people increasingly stupid when it comes to the awareness of their basic biological functions.

Do you really need an Oura ring to tell you how you slept last night, or is it possible that you could simply reflect on how refreshed you felt, when you woke up this morning? Is that heart rate monitor really helping you to train more efficiently, or is it making you lose touch with your ability to sense how hard you're working2? And do you really need a CGM to guide your food choices, or would you be better off selecting your diet based on some simple criteria such as, 'Can I look at that food, and immediately recognise it as something that was created by natural processes, or was minimally processed, by me, from natural ingredients?'

There may well be some benefits to using CGMs for some people (in particular, insulin-dependent diabetics), and the technology will no doubt become more accurate, reliable and reproducible over time, which will expand its use cases.

But the fact that so many 'health influencers' and for-profit companies are heavily promoting the use of CGMs, in their current inaccurate, unreliable and poorly reproducible state, by subsets of the population who cannot possibly benefit from them and may indeed suffer harms from being misled into making unhealthy dietary choices, is hugely concerning to me.

At this point in time, my advice would be that if your health practitioner recommends that you use a CGM (assuming that you're not an insulin-dependent diabetic), you should probably find a new practitioner. And if someone you've been following on social media starts spruiking a CGM, I'd suggest unfollowing them. Your health is your most precious possession; don't compromise it by taking advice from ignorant people.

Last thing: This post took me approximately 20 hours to research and write. If you feel you’ve gotten value from it, please consider a paid subscription to help me continue this work:

For information on my private practice, please visit Empower Total Health. I am a Certified Lifestyle Medicine Practitioner, with an ND, GDCouns, BHSc(Hons) and Fellowship of the Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine.

As journalist Naomi Wolf has discussed at length, Levels has some extremely odd features. It has attracted an extraordinary amount of funding from Silicon Valley venture capitalists including prominent figures from Google, SpaceX, Netflix and Twitter/X, and has a current market valuation of $313 million despite having only acquired 60,000 subscribers in its six-year history, almost eight out of ten of whom reside in Mexico, a country with an average monthly salary that would put Levels' expensive membership fees out of reach of most of the population. I highly recommend reading Naomi Wolf's deep dive on Casey Means (and her brother, Calley Means) at The Imaginary Casey Means.

Red_Pill_Aussie highlighted a valuable use case for heart rate monitors, namely in people with a cardiac history:

“Finally on heart rate monitors, I am under instructions from my cardiologist to keep max heart rate at 140 BPM when exercising. I am constantly amazed it exceeds that when running or rowing but I feel like I'm only going at 70% effort and could go easily go much harder and am tempted. Without the chest strap monitor, I'd have no idea I was exceeding the limit advised, so again, I see good benefits for some cases but for young fit athletes, noticing body feelings should be good enough.”

Thanks for a great article Robyn. I'm passing on to the team at Apollo Health to get a comment from Dr Dale Bredesen, who has been a strong advocate of these. However, diabetes expert, Dr Wes Youngberg has mentioned there is a difference between Freestyle Libre and Dexcom. One observation though from health coaching and having clients use a CGM - many clients hate the idea of needle pricks all the time and the CGM's certainly show trends such as big spikes after meals that we would otherwise only find with needle pricks or not discover.

Usually, these spikes are very high and at least we know there is bad insulin resistance. But as the studies show, using them to fine tune diets sounds like a bad idea once insulin sensitivity has been restored, so I think they have a place initially but not for long term use.

Regrading sleep monitors such as the Oura ring, Dr Bredesen has warned that these in particular are not necessarily accurate but to do show trends over time. Haven't used one myself but Have used a cheapie Oximeter that monitors blood oxygenation through the night and IMO, these are very helpful. It showed I had undiagnosed low blood oxygen overnight due to airway obstruction and once I changed sleeping positions,used a device to help nose breathing and used mouth tape, slept much better, woke much more refreshed and the meter showed much improved oxygen levels through the night, so for about $120, I thought this was great value.

Finally on heart rate monitors, I am under instructions from my cardiologist to keep max heart rate at 140 BPM when exercising. I am constantly amazed it exceeds that when running or rowing but I feel like I'm only going at 70% effort and could go easily go much harder and am tempted. Without the chest strap monitor, I'd have no idea I was exceeding the limit advised, so again, I see good benefits for some cases but for young fit athletes, noticing body feelings should be good enough.

This article helped me think about my mom. She asked me to help her get CGM. She has A1C of 7.6. Trials do show reduction in A1C in diabetics. But my take is this:

1. She's high anxiety and this is more fuel for that.

2. Anxiety can lead to irrational decisions. For example she loves mangos. Evidence suggests they don't worsen blood sugar. But if she gets readings that says she is uniquely sensitive she may stop. Never mind the reading could be wrong. Even if right, it's not a hard end point and the phytochemicals may still be worth it.

3. She takes lots of supplements. Confounding with readings is unknown - at least to me. Ascorbic acid supplements do cause false spikes on some finger prick devices.

4. While the inaccurate readings are shown in studies of healthy people, I am not aware that any studies show this is not also the case in diabetics.

5. The reason for benefit to A1C in diabetics is probably unproven. A sham control is needed. Probably studies lack them and I'm too jaded to spend the time to hope otherwise. Completely fake readings could also improve diet choices.

Probably the best thing to do is just find other ways to motivate people that aren't all that hassle.

Edit: I agree with the point that factors other than diet are an issue, and that confounds things.