Obesity: Bad to the Brain

Research on the effects of obesity on the human brain has made significant progress since I last wrote about this topic, in an article called How to make an 'obese brain': Just add saturated fat. That article summarised the finding of research on high fat diet and obesity on rats.

Since then, researchers have moved on to studying the brains of obese humans. As usual, there's bad news and good news to report from their findings.

Starting with the bad news, obesity reduces blood flow to the brain, decreases neuroplasticity (the ability of brain cells and neural networks in the brain to change their connections and behaviour in response to new information, damage, or dysfunction), and ramps up the activity of 'impulsive' neural circuits that can lead to overeating, while dampening the activity of 'reflective' circuits that discourage it.

Let's examine these findings one by one, starting with blood flow.

1. Obesity reduces cerebral blood flow

Our brains, despite comprising only about 2.5% of our body weight, receive almost 15% of cardiac output (the amount of blood pumped out of the heart each minute). The lump of grey matter between your ears needs a lot of blood to nourish it and remove the wastes generated by its activities! Blood flow to our brains declines as we age, but researchers wanted to know whether being obese might accelerate that decline.

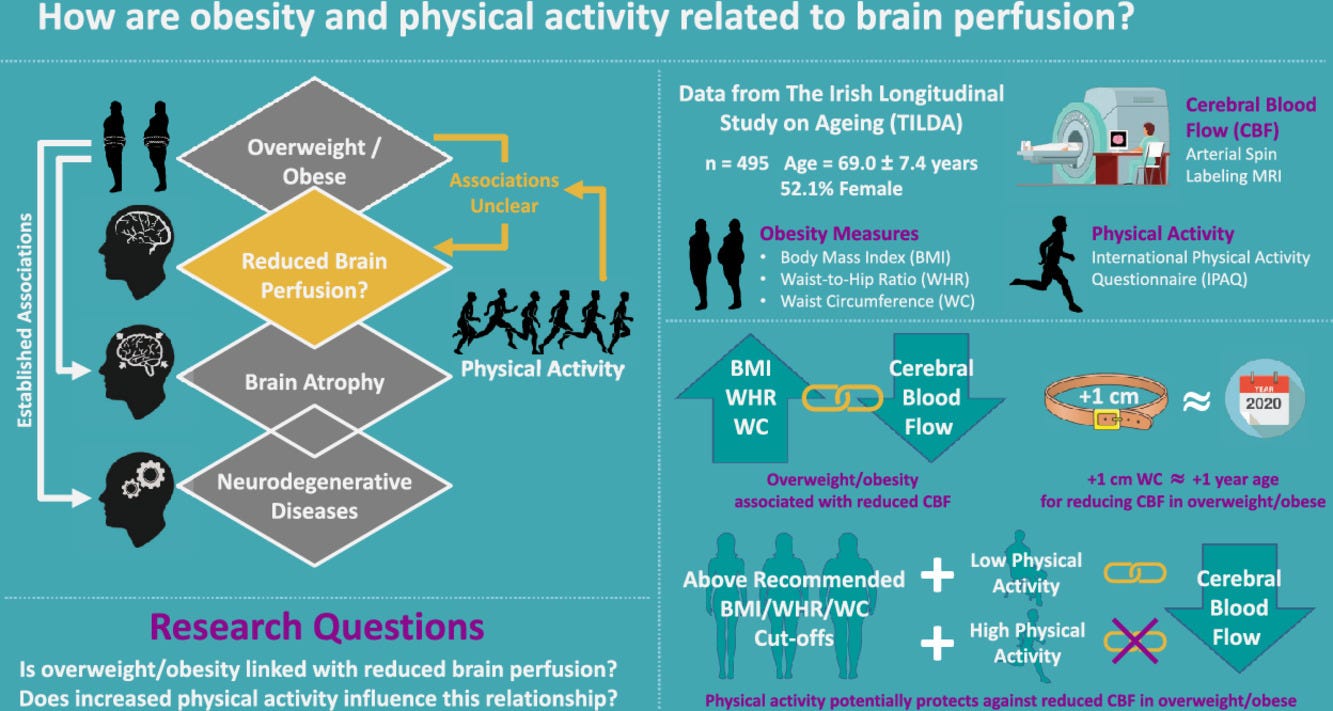

They recruited participants in The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA), an ongoing nationally-representative prospective cohort study of community-dwelling Irish adults (1 in 150 individuals in Ireland aged ≥50 years), to undergo brain blood flow measurement using cutting-edge MRI scanning and analysis techniques.

The researchers assessed obesity using three different measures: body mass index (BMI - weight in kg divided by height in centimetres, squared), waist to hip ratio (WHR - waist measurement divided by hip measurement) and waist circumference (WC). By BMI, 71% of participants were classified as overweight/obese, while 69% were above the World Health Organisation (WHO) cut-off for WHR and 77% were above the WHO cut-off for WC.

Associations were found between all three measures of obesity and reduced cerebral blood flow. And all three measures had an equal or greater effect than aging, which reduces cerebral blood flow by 0.13−0.15 ml per 100 g of brain weight per minute, for each extra year on the calendar.

In fact, for every 1 point increase in BMI, blood flow to the brain reduced by 0.34 ml per 100 g of brain weight per minute. For each 0.1 increase in WHR, blood flow decreased by 1.29 ml/100g/min. And every extra centimetre of waist circumference cut blood flow by 0.13 ml/100g/min. p = 0.019).

Diminished cerebral blood flow increases the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia, which older people fear more than any other disease including cancer.

Stroke (cerebrovascular accident) is another condition that people fear as they get older, since most have encountered at least one person who has suffered cognitive and/or physical disability after surviving this 'heart attack of the brain'. And that leads us on to study #2...

2. Obesity reduces neuroplasticity

Our brains are remarkable in their ability to grow, evolve and adapt in response to life experiences. This neuroplasticity allows the 1.3 kg lump of delicate, shimmering grey and white matter between our ears to respond to new information, sensory stimulation, development, damage, or dysfunction.

Unfortunately, obesity impairs this crucial ability of the brain to form new connections and pathways and change how its circuits are wired - at any age.

To study the effects of obesity on neuroplasticity, researchers recruited 15 obese people aged between 18 and 60, and 15 healthy-weight people matched for gender and age.

Each group was exposed to transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a noninvasive form of brain stimulation in which a changing magnetic field is used to cause electric current at a specific area of the brain. TMS is used to improve the symptoms of depression in people who have not responded to other forms of therapy. The electrical activity that it generates is known to stimulate neuroplasticity.

However, the researchers found that while the brains of healthy-weight people responded promptly and vigorously to TMS, the brains of obese people showed a minimal response, indicating reduced neuroplasticity.

The researchers warned that this impaired capacity to adapt to change had worrying implications in "various clinical patient groups where learning is fundamental for recovery, such as after stroke or in mild cognitive impairment."

In other words, carrying excess body fat could hamper a person's ability to regain their function after a stroke, and to slow the progression of mild cognitive impairment into dementia.

However, as any obese person will tell you, losing weight and keeping it off is not so easy. That's because obesity itself changes the structure and function of the brain, which leads us on to study #3...

3. Obesity alters the brain, making high-calorie food more rewarding and restraint more difficult

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), researchers studied brain structure and function in 36 healthy-weight teenagers and 34 overweight teens.

The overweight teens were found to have increased activity in neural circuits that are involved in the reward response to appetising food, and lower activity in neural circuits that allow us to reflect on the consequences of our choices and thereby exercise restraint.

In addition, there were differences in the thickness of the cerebral cortex in brain regions associated with impulsivity and restraint.

This study should encourage us all to have compassion for people who struggle to attain and maintain a healthy weight. For those who maintain a healthy weight with ease, it is almost impossible to imagine just how difficult it would be to pass up calorie-dense food when your brain is screaming at you to eat as much of it as you can!

The good news

Fortunately, there is light at the end of the tunnel. Firstly, the researchers who carried out the brain blood flow study found that physical activity offset the harmful effect of obesity on cerebral perfusion (see graphic below).

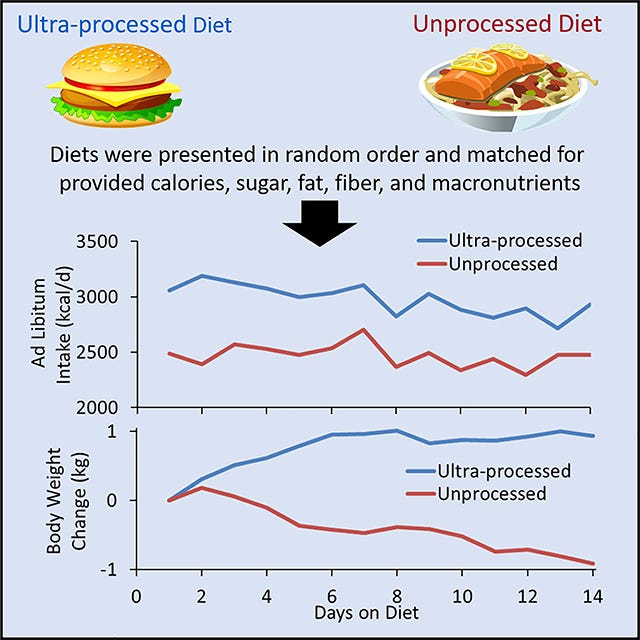

And secondly, meticulous research conducted by Kevin Hall has shown that both when overweight adults eat either an unprocessed diet or a low-fat, plant-based diet, but are permitted to eat as much as they desire, they spontaneously and unconsciously decrease their calorie intake.

The differences in calorie intake and weight loss are startling. Here's a graphical summary of the results of the unprocessed diet on calorie intake and weight:

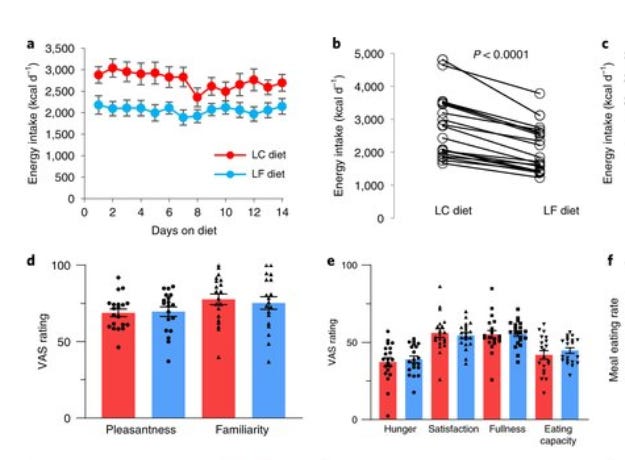

And here's an illustration of the effects of a low-fat plant-based diet vs a low-carbohydrate animal-based diet on energy intake, enjoyment of food, desire to eat and fullness after eating:

To summarise, regular movement helps the brain receive sufficient blood flow while a low-fat wholefood plant-based diet allows people to reduce their energy intake without feeling hungry all the time.

So don't lose hope, even if you've struggled with your weight for as long as you can remember. The science of obesity's effects on the brain may be complex, but the solution to the problem is not.