Ketogenic diets: Part 3 - Weight loss

Is a ketogenic diet really the best way to lose weight? Not according to the weight of scientific evidence.

In Part 1 of this series, I discussed the origins of the ketogenic diet and the biological role of ketone bodies. Part 2 addressed the question of whether a ketogenic diet (and by extension, living in a state of near-permanent ketosis) is natural to humans. But let's face it: most people who are attracted to the ketogenic diet don't really care about these issues. They just want to know,

"Will it help me lose weight?"

And that’s what I’m covering in this post.

To ketogenic diet advocates, the hormone insulin is the big baddie that makes us fat. The carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis that they espouse states that eating a high-carbohydrate diet drives up insulin levels, causing fat to accumulate in adipose tissue and suppressing energy expenditure, thus lowering metabolic rate.

They claim that ketogenic diets offer a metabolic advantage over every other type of weight loss diet in that exchanging an equal number of calories from carbohydrate for calories from fat will drive down insulin levels, increase energy expenditure/metabolic rate, increase the oxidation of fat as a fuel, and therefore result in increased loss of body fat. “A calorie is not a calorie” – or so they claim.

But are these claims backed up by scientific research?

Putting ketogenic diets to the test

First up, the idea that ketogenic diets offer a metabolic advantage over low carbohydrate diets that aren’t ketogenic was tested back in 2006. Obese adults were randomly assigned to either a ketogenic diet (60 per cent energy from fat and 5 per cent from carbohydrate at the beginning) or a nonketogenic low-carbohydrate diet (30 per cent of energy from fat, 40 per cent from carbohydrate) diet for six weeks. Participants’ diets were strictly controlled throughout the study, and they were kept sedentary in order to prevent weight loss or body composition change due to exercise from confounding the results.

The results weren’t exactly heartening for keto enthusiasts. There was no significant difference in weight loss (average loss of 6.3 kg in the ketogenic dieters vs 7.2 in the non-ketogenic low-carb dieters) or fat loss (3.4 kg in the ketos vs 5.5 kg in the non-ketos).

On the other hand, one participant assigned to the keto group developed heart arrhythmia (a known side-effect of ketogenic diets) during the first week of the study and had to drop out; the inflammatory risk profile increased in the keto dieters; and they also reported lower vigour and poorer mood state.

Low-carb enthusiasts claim that cutting dietary carbohydrate results in greater loss of body fat than cutting dietary fat, because carbohydrate restriction increases the amount of fat oxidised as fuel. This theory was put to the test by a team led by prolific weight loss researcher Kevin Hall, in 2015. 19 obese adults were confined to a metabolic ward (i.e. a dedicated research facility or hospital ward where the only food consumed is that supplied by the researchers) for two x two-week periods to test the effects of a reduced fat vs reduced carbohydrate diet. The volunteers did one hour of exercise per day on a treadmill, and were otherwise sedentary during their time in the metabolic ward.

For the first five days of each visit, they were fed a baseline diet (50 per cent carbohydrate, 35 per cent fat, and 15 per protein). Then they were put on one of the test diets for two weeks, returning after a two to four-week “washout” period to do the other diet, so their results on each diet could be compared. Both test diets contained 30 per cent fewer calories than the participants’ customary diets, with the reduction being achieved either by cutting fat or cutting carbohydrates. The protein content of both test diets was the same, to enable the researchers to directly compare the effects on weight loss of reducing dietary fat vs carbohydrate.

And the results were…

Body fat loss was greater on the low fat diet (89 g per day) than the low carb diet (53 g per day), despite fat oxidation rising only on the low carb diet! As the researchers concluded,

“This study demonstrated that, calorie for calorie, restriction of dietary fat led to greater body fat loss than restriction of dietary carbohydrate in adults with obesity. This occurred despite the fact that only the carbohydrate-restricted diet led to decreased insulin secretion and a substantial sustained increase in net fat oxidation compared to the baseline energy-balanced diet.”

But wait, said the keto enthusiasts – the low carbohydrate diet used in this study wasn’t low-carb enough. It comprised 30 per cent of energy from carbohydrate and 50 per cent from fat. A truly ketogenic diet, they insisted, would have resulted in more fat loss due to the “metabolic advantage”.

So the same lead researcher, Kevin Hall, tested a truly ketogenic diet the following year. The study was breathtaking in its design and execution. 17 overweight or obese men were confined to a metabolic ward for eight weeks. For the first four weeks, they were fed a relatively high-carbohydrate baseline diet (50 per cent carbohydrate, 15 per cent protein, 35 per cent fat), followed by four weeks on a ketogenic diet (5 per cent carbohydrate, 15 per cent protein, 80 per cent fat) with the same number of calories as the baseline diet. This “crossover” study design meant that each man served as his own control.

Their energy expenditure was measured during sleep and waking times, and their body composition changes were measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans. They were prescribed 90 minutes of low-intensity aerobic exercise per day on an exercise bike.

And the results were…

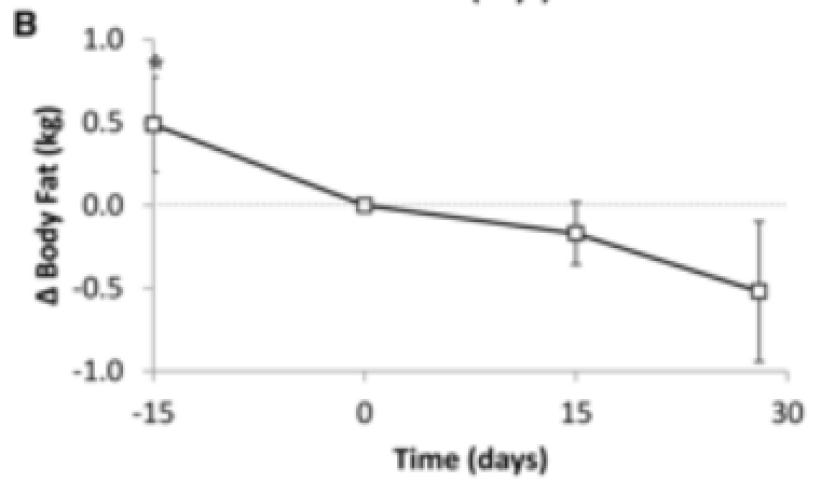

Although the baseline high-carbohydrate diet was not intended to cause weight or fat loss, subjects lost 0.8 kg in their last 15 days of it, with 0.5 kg of that weight loss coming from body fat. However, despite a small increase in energy expenditure on the ketogenic diet, body fat loss actually slowed down compared to fat loss on the high carbohydrate diet.

The diagram below illustrates this: the slope of the fat mass loss shows faster fat loss in the last 15 days of the higher carbohydrate diet (15-0), and slower fat loss in the first 15 days of the ketogenic diet. It took the entire 28 days on the ketogenic diet to lose the same amount of fat as participants lost during the last 15 days of the high carbohydrate diet:

Participants experienced a rapid loss of 1.6 kg of overall weight when they commenced the ketogenic diet phase, with a total loss of 2.2 kg over their 4 weeks on keto:

However, only 0.5 kg of that was from loss of body fat. And all this despite a 47 per cent reduction in levels of that dreadful fat-making hormone, insulin. So much for the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity!

To add insult to injury, fat-free mass (muscle, bone and vital organs) declined on the ketogenic diet. Urinary nitrogen excretion increased, indicating significantly increased protein utilisation – remember, certain cells in the body, including red blood cells and cells in part of the kidneys, are unable to use any fuel except glucose, so if insufficient carbohydrate is supplied in the diet, the body will break down protein to turn its amino acids into glucose to fuel these cells.

So what did this meticulously-conducted study reveal about weight loss on a ketogenic diet? The initial rapid weight loss that lures people into following these diets is simply from depletion of glycogen and the water it holds, as explained in Part 1. However, ketogenic diets are not good for fat loss, which is, after all, what counts. Instead, they deplete fat-free tissues, including the vital muscle mass that maintains a healthy metabolic rate and helps to prevent weight gain as we age.

Why don’t ketogenic diets work well for fat loss? The researchers speculated:

“We suspect that the increased dietary fat resulted in elevated circulating postprandial [after-meal] triglyceride concentrations throughout the day, which may have stimulated adipose tissue fat uptake… and/or inhibited adipocyte lipolysis [breakdown of fat from fat cells, to use for energy production]. These mechanistic questions deserve further study, but it is clear that regulation of adipose tissue fat storage is multifaceted and that insulin does not always play a predominant role.”

Does the ketogenic diet suppress appetite?

Weight loss is well known to result in an increased appetite, which is one of the primary reasons most diets fail. Keto enthusiasts claim that weight loss – and maintenance of goal weight – is easy on a high fat, low carbohydrate diet because ketone bodies suppress appetite during the weight loss process, and prevent the rebound increase in appetite that usually sabotages the dieter’s best intentions.

But a study of the effects of an eight week low energy ketogenic diet on hunger perception and appetite hormones in obese men and women found that appetite was increased in the first three weeks of the diet, then levelled off for the remaining five weeks. However, once participants returned to a more normal energy intake, their appetites came back with a vengeance – both hunger feelings and the concentration of the “hunger hormone” ghrelin were significantly higher than at baseline, before they started the diet.

Furthermore, proponents of ketogenic diets claim that high-carbohydrate diets lead to excess insulin secretion, which drives increased appetite and therefore, higher energy (calorie/kilojoule) intake. If this hypothesis were correct, ketogenic diets should suppress appetite resulting in decreased energy intake.

Yet another meticulously-conducted study led by Kevin Hall, this time of a plant-based, low-fat diet versus an animal-based, ketogenic diet, once again found exactly the opposite.

For this study, published in February 2021, 20 overweight adults stayed in a metabolic ward for four weeks. They were assigned to follow either a minimally processed, plant-based, low-fat diet (10 per cent of calories from fat, 75 per cent from carbohydrate) with high glycaemic load (85 g per 1000 kcal) or a minimally processed, animal-based, ketogenic, low-carbohydrate diet (75 per cent fat, 10 per cent carbohydrate) with low glycaemic load (6 g per 1000 kcal) for 2 weeks, followed immediately by the alternate diet for 2 weeks.

Again, the genius of this study design is that every participant serves as his or her own control, allowing researchers to compare the effects of both diets on each individual.

Participants were instructed to eat ad libitum – that is, as much as they wanted, until they were full – from meals prepared according to the specified macronutrient ratios for each test diet. Their actual food intake was tracked to make sure they didn’t deviate substantially from these ratios.

During the low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet phase, participants ate on average 689 fewer kcal per day than during the low-carbohydrate diet phase, regardless of the order in which they undertook the two different diet patterns. Despite consuming substantially fewer calories during the low-fat plant-based phase, participants rated themselves just as satisfied and full after they had finished eating, compared to the low-carbohydrate animal-based phase:

Low-carb vs low-fat diets for weight and fat loss

Low-carb and keto enthusiasts blame the burgeoning global obesity epidemic on the promotion of low-fat diets by health authorities (despite a distinct lack of evidence that dietary guidelines make the slightest difference to most people’s food choices). If they’re correct, we should see evidence of greater weight loss in people following low-carbohydrate diets than low-fat diets.

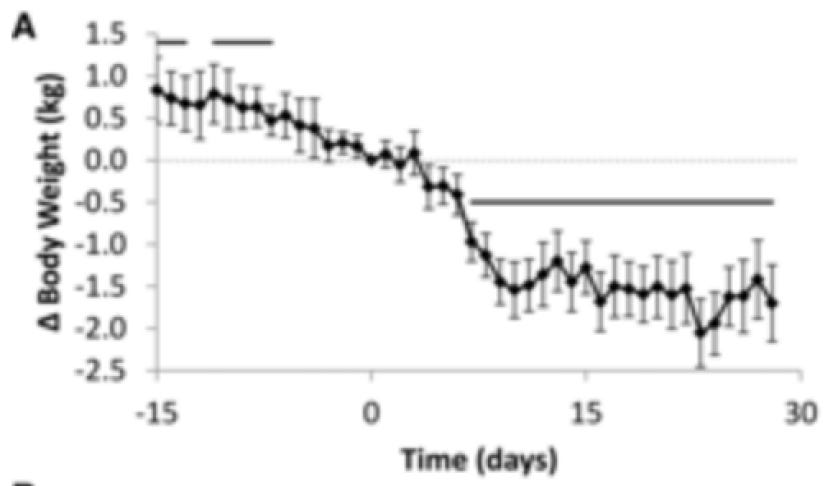

However, a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled feeding studies which measured the effects on daily energy expenditure (“metabolic rate”) and body fat of diets with the same amount of calories and protein, but different ratios of carbohydrate to fat, found that people assigned to low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets burnt more calories and lost more body fat than people assigned to high-fat, low-carbohydrate diets, although the differences were so small as to be clinically meaningless:

And an umbrella review of published meta-analyses and systematic review of trials of diets for weight loss in diabetics, published in 2021, found that “low-carbohydrate diets were no better for weight loss than higher-carbohydrate/low-fat diets.”

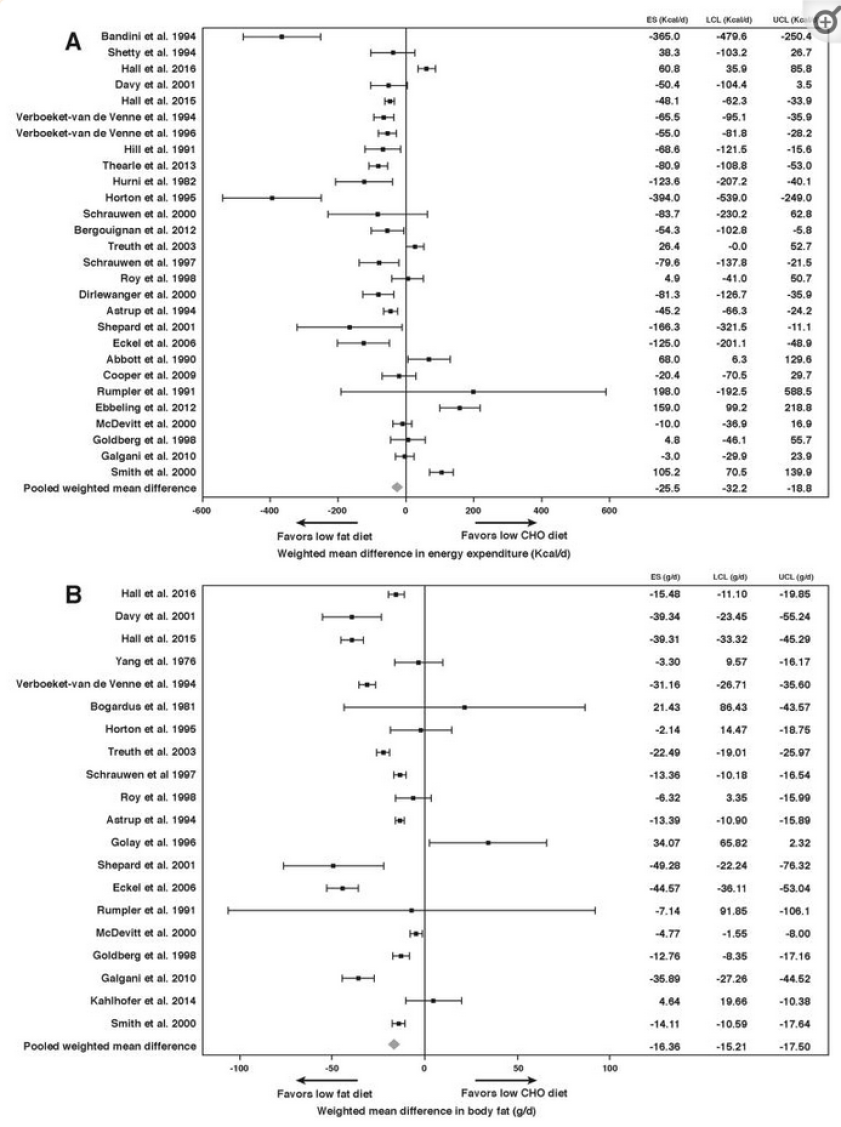

But no better than is weak sauce. In the metabolic ward study referenced in the previous section, weight loss occurred more rapidly in the first week of the ketogenic diet phase than the low-fat phase, but by the end of the second week, the difference in weight loss between the two diet-styles was not statistically significant (1.77 kg lost on the ketogenic diet vs 1.09 kg on the low-fat plant-based diet).

However, whereas most of the weight lost on the low-carbohydrate diet – 1.61 kg out of the 1.77 kg total weight loss – was from fat-free mass (muscle, organs and bones), only 160 g of the 1.09 kg lost on the low-fat diet came from fat-free mass.

Consequently, while body fat mass was not significantly changed at the end of two weeks on the ketogenic diet (180 g lost), on the low-fat diet participants’ fat mass reduced by 270 g at the end of the first week and 670 g by the end of the second week:

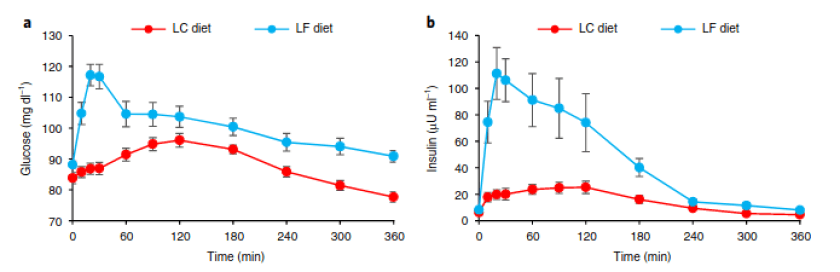

Notably, the reduction in fat mass on the low-fat plant-based diet occurred despite blood glucose and insulin levels rising significantly higher after meals during this phase than whilst on the ketogenic diet, contrary to the predictions of the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity propounded by low-carbohydrate diet enthusiasts:

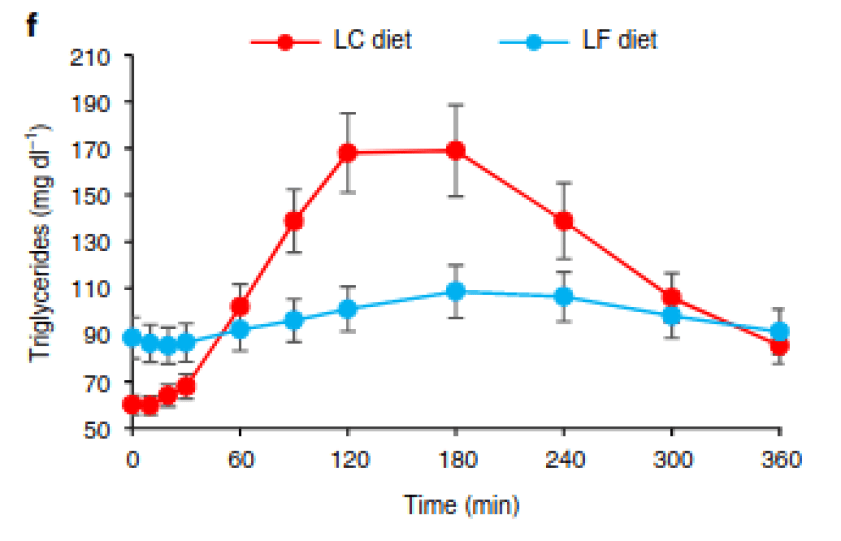

In the 2016 paper cited above (‘Energy expenditure and body composition changes after an isocaloric ketogenic diet in overweight and obese men‘), Kevin Hall and his team had hypothesised that high dietary fat intake may lead to persistently elevated concentrations of triglycerides (blood fats) throughout the day, which in turn may stimulate adipose tissue to take up and store fat and/or inhibit the release of free fatty acids from fat stores, to use for energy production.

And sure enough, in their 2021 study, while fasting triglyceride concentrations were lower during the animal-based ketogenic diet phase, triglycerides rose substantially higher after ketogenic meals, and remained substantially elevated for several hours, compared to when participants were eating a low-fat plant-based diet:

Although this finding doesn’t prove that persistently elevated post-prandial triglyceride levels induced by a ketogenic diet inhibit body fat loss, it certainly provides tantalising evidence for Hall’s hypothesis.

All in all, participants lost on average 35 g of body fat more per day while on the low-fat plant-based diet than the ketogenic diet (51 g per day vs 16 g per day). To be sure, these are not large numbers, but over time, adherence to a low-fat plant-based diet would be expected to result in substantially more body fat loss, with preservation of vital fat-free mass, than an animal-based ketogenic diet.

But this study measured the effects of two radically different diet-styles in the tightly-controlled setting of a metabolic ward, where participants only have access to the food that researchers give them. What happens when a low-fat plant-based diet is implemented “in the wild”? Allow me to introduce you to the BROAD Study.

Real-world evidence of what actually works for weight loss

The most effective dietary intervention for long-term weight loss ever published in a peer-reviewed journal, the BROAD Study, used the polar opposite of a ketogenic diet. Overweight and obese patients from a single GP practice in Gisborne, New Zealand were taught to eat a very low fat (< 15 per cent fat), high carbohydrate, wholefood plant-based diet. Participants were instructed to eat ad libitum (that is, until they were full, with no portion control) and were not prescribed any exercise. Weight loss at six months averaged 12.1 kg, and at 12 months, 11.5 kg. As the authors concluded,

“To the best of our knowledge, this research has achieved greater weight loss at 6 and 12 months than any other trial that does not limit energy intake or mandate regular exercise.”

As mentioned in previous articles, low carbohydrate diets are associated with a higher risk of death, especially from heart disease and cancer. And they don’t work as well as (truly) low fat, high carbohydrate diets for either weight loss or fat loss. Their continuing dominance of the zeitgeist is testimony to the human propensity to ignore the facts in favour of fairytales. But when it comes to ketogenic diets and successful, long term weight loss, the emperor truly has no clothes.

Yes exactly, healthy foods flavour themselves and prep is made simple and easy. Mulberries are manna from heaven, 4 days ago I started picking my white ones, the dark ones will take another week or so to ripen. My focus in the garden has been fruit trees, herbs and greens. I should grow more veggies, but there’s good organic produce within walking distance. It’s quite special eating one’s own home-grown food….

Thanks Robyn, that’s a great reminder that foods are indeed synergistic blends of many components. I can’t agree more about minimal processing, this is a big key to good health. Find clean raw foods and learn simple prep methods. Cheers for the links also!