The inflammation discombobulation

Do nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs turn acute pain into chronic pain?

In last week's article, Osteoarthritis: Curse of old age or plague of modernity?, I discussed the concerning finding that people with osteoarthritis who take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen and naproxen regularly, end up with worse joint inflammation and cartilage quality that those who do not use NSAIDs.

Osteoarthritis is a chronic inflammatory condition. Are NSAIDs any better for acute pain - that is, pain that comes on abruptly - such as a sprained ankle, muscle tear or sudden-onset low back or jaw pain? NSAIDs are widely used by the public, and recommended by doctors, for exactly this purpose. For example, both the National Prescribing Service (NPS) and the Emergency Care Institute recommend the use of NSAIDs for acute low back pain.

But an international team of researchers, drawing on data from animal experiments and human patients with low back pain or temporomandibular disorder, have concluded that the use of NSAIDs for acute pain conditions could increase the risk of developing chronic pain.

To understand these disturbing findings, we first need to grasp some basic facts about the role that inflammation plays in the response to injury. As I mentioned in my previous article, Stop calling them ‘side effects’, "acute inflammation [is]... the vital second step in initiating the wound or injury healing process."

After the formation of a blood clot at the site of blood vessel injury (haemostasis, the first step in healing), multiple different types of white blood cells swing into action, in a tightly-choreographed dance of biological activities that first enforces protection and rest of the damaged part, and then orchestrates its clean-up and repair:

"Mast cells release granules filled with enzymes, histamine and other active amines, which are responsible for the characteristic signs of inflammation, the rubor (redness), calor (heat), tumor (swelling) and dolor (pain) around the wound site. Neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages are the key cells during the inflammatory phase. They cleanse the wound of infection and debris and release soluble mediators such as proinflammatory cytokines (including IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α), and growth factors (such as PDGF, TGF-β, TGF-α, IGF-1, and FGF) that are involved in the recruitment and activation of fibroblasts and epithelial cells in preparation for the next phase in healing."

Note the central role of neutrophils - a subtype of white blood cell - in the acute inflammatory response. That brings me back to the article on the role that NSAIDs play in the transition from acute to chronic pain. The title, 'Acute inflammatory response via neutrophil activation protects against the development of chronic pain', kinda sorta gives the game away.

In a nutshell, the researchers found that individuals who have more inflammation, and most particularly, enhanced neutrophil activity during the acute inflammation stage, are more likely to experience full resolution of inflammation, and its associated pain, three months later. Furthermore, use of NSAIDs, which reduce the activation and activity of neutrophils, is associated with an almost 80 per cent higher risk of developing chronic back pain.

The paper reports a series of tests and experiments that led the researchers to these conclusions. Let's break them down.

1. Low back pain sufferers

98 patients who presented to their local doctor or hospital emergency department with acute low back pain gave blood samples, which were analysed for white blood cell subtypes and transcriptomics, or which genes in their genome were being expressed. Three months later, they returned to report whether their acute back pain had resolved, or was still persisting, and to give more blood samples on which the same tests were performed in order to track any changes in biomarkers.

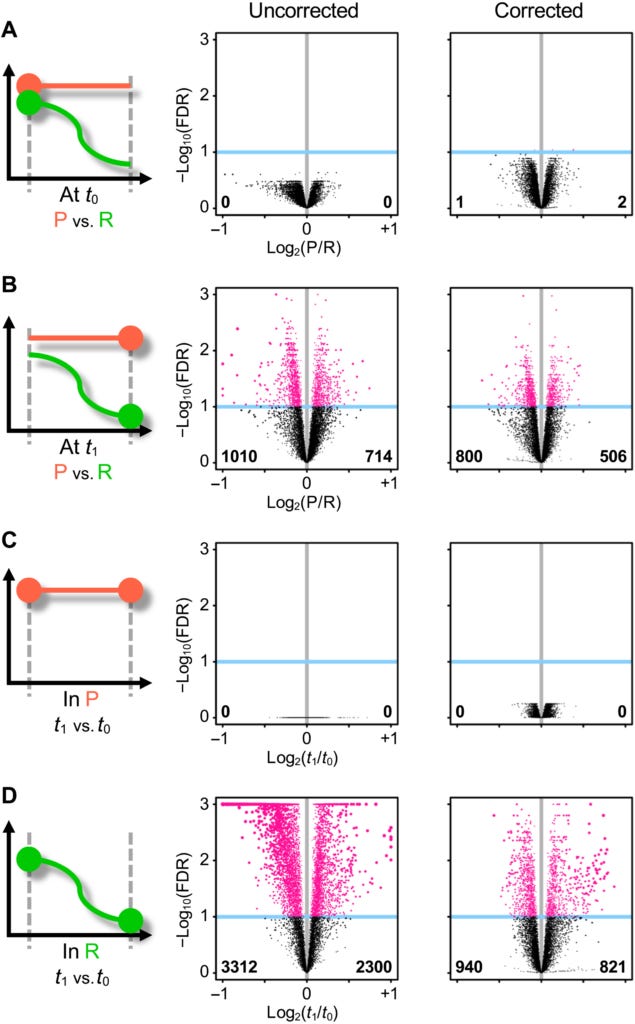

In those whose low back pain had resolved by the second visit, more than 5500 genes were differentially expressed compared to the first visit. By contrast, there was no change in gene expression between the first and second visits in patients with persistent pain. Comparing the patients with persistent pain to those whose pain had resolved, the researchers identified more than 1700 genes that were differentially expressed between the two groups.

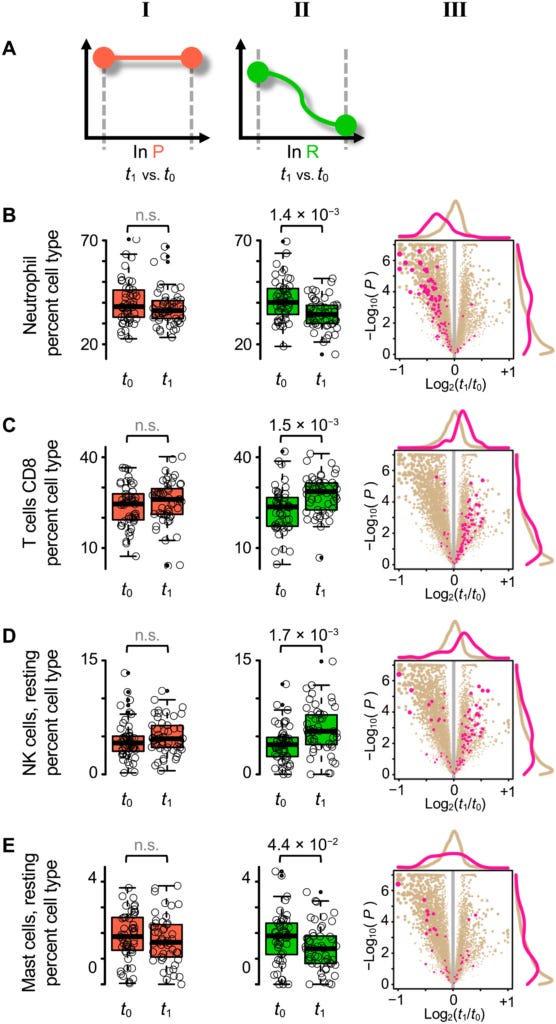

In patients who had recovered from their acute low back pain, there were also statistically significant differences in the levels of four different white blood cell types, between the first and second visits. The largest difference was in neutrophil count, which declined over time. The number of resting mast cells also decreased between the two visits, whereas the CD8+ T cells and resting natural killer cells increased. However, in patients with persistent low back pain, there was no change in white blood cell type populations over time. It was as if these patients had got 'stuck' in an early stage of the healing process, and never progressed beyond it.

Comparing the changes in gene expression to the changes in white blood cell subtypes, the researchers found that, indeed, the genes that had changed expression in the recovered patients had to do with white cell subtypes, with neutrophil-specific genes showing the largest drop in activity between the first and second visits.

Turning to the biological pathways that are 'switched on' or 'switched off' by differential expression of various genes, the researchers made the somewhat startling discovery that the biggest difference between the patients who recovered from their acute low back pain versus those who had persistent pain, was that the recovered group had elevated cell activation and immune response pathways when they first sought medical attention for their pain, with neutrophil activation and degranulation being particularly upregulated.

In plain English, those who had recovered from their episode of acute pain had a stronger initial inflammatory response than those with persistent pain, which then abated over time. Let that sink in: more inflammation during the acute phase was associated with a higher chance of complete recovery.

"This unexpected [neutrophil-driven] enhanced inflammatory response in R [recovered] participants was consistently observed for other related inflammatory pathways... With time, there were barely any changes in the inflammatory response pathways in the P [persistent pain] group... However, in the R group, the inflammatory response pathways were convincingly down-regulated over time, at t1 [second visit] compared to t0 [first visit]."

2. Temporomandibular disorder sufferers

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is a painful condition of the jaw joint and the muscles controlling jaw movement.

The researchers wanted to determine whether the patterns of gene expression and biological pathways they had identified in people with low back pain, would also be seen in people with TMD. They recruited 118 patients who presented with TMD pain for the first time in their lives, and returned for a follow-up visit six months later.

Once again, they found a larger number of differentially expressed genes in people who had fully recovered from their acute TMD at their six month follow-up compared to those whose TMD pain had persisted. And, at the first visit, the recovered group had elevated activity of inflammatory and neutrophil activation and degranulation pathways.

This arm of the study included a control group of people who did not have TMD. In comparison with these healthy controls, the group who subsequently recovered from TMD had a significantly higher inflammatory response at their first visit, while those with persistent TMD pain at six months had a reduced inflammatory response. At the six month follow-up, both TMD groups displayed a significantly reduced inflammatory response compared to the healthy group.

The researchers summarised their findings as follows:

"These results indicate the importance of the up-regulation of inflammatory response at the acute stage of musculoskeletal pain as a protective mechanism against the development of chronic pain."

Again, in plain English, the hotter the flame of inflammation burns during the acute phase, the lower the risk of it smouldering into chronic pain.

3. Animal studies

The researchers performed a number of studies in mice to further elucidate the mechanisms behind the phenomena they had observed in low back pain and TMD pain sufferers. I'm not going to dwell on these because, to be perfectly honest, the needless cruelty of animal experiments appals me. I wouldn't be surprised if much of the frankly sociopathic behaviour we've observed in many scientists during the manufactured COVID crisis is cultivated by the culture of cavalier disregard for the suffering and death of over 192 million animals used in laboratory experiments per year, into which they are inculcated.

Suffice it to say that these animal experiments confirmed the pivotal role that active inflammatory responses, particularly those regulated by neutrophils, play in pain resolution. When the researchers suppressed this inflammatory response, either by giving the mice dexamethasone (a steroidal anti-inflammatory drug) or diclofenac (an NSAID), or by depleting neutrophils, the mice suffered from prolonged pain in response to a number of mechanical and chemical pain-inducing stimuli.

4. Relationship between back pain and use of pain-relieving medication

Using the UK Biobank cohort, which I've referred to in many previous articles, the researchers assessed the relationship between self-reported back pain and the use of several classes of analgaesic (pain-relieving) medications with different mechanisms of action, including NSAIDs, paracetamol (acetaminophen), and antidepressants. Of these, only NSAIDs relieve pain via suppression of inflammation.

Individuals with acute back pain who reported using NSAIDS had a 1.76-fold greater risk of developing chronic back pain than those who did not take NSAIDs. No other class of analgaesic drug was found to be associated with an increased risk of progressing to chronic back pain.

Furthermore, the lower the percentage of neutrophils present at the acute stage, the higher the chance the individual would go on to develop chronic back pain.

Drawing it all together

In a nutshell, the inflammatory response to acute injury, while painful, is absolutely necessary to promote complete healing and prevent the development of chronic pain:

"An active biological process underlies pain resolution rather than pain progression to chronic status. Our results suggest that this process is impaired in those who do not resolve acute pain over time... the beginning of the inflammatory process programs its resolution..., and it is thus the failure to initiate an appropriate inflammatory response that may lead to chronic pain."

NSAIDs, which alleviate pain by suppressing inflammation, buy us a temporary reprieve from the acute pain of injury, at the price of interfering with healing, and setting us up for chronic pain.

Yet again, the cleverness of allopathic medicine has outpaced its wisdom. The arrogant assumption that the inflammatory response to acute injury is a malfunction of biological processes leads to the incorrect assumption that a drug is required to correct the ‘disorder’. In reality, the inflammatory response is a symphony of biological processes working ingeniously towards healing, and all that is required for it to work its miracles is that we do nothing, intelligently.

Very interesting Robyn and have seen this before about the wisdom of letting the inflammation response do its thing instead of suppressing with drugs. Now, does that also mean we should not ice, apply elevation and compression to acute pain from injuries like say a sprained ankle?

Do nothing, intelligently! I love it.