Preventing dementia: Part 1

With dementia now the 2nd leading cause of death in Australia, a comprehensive strategy for preventing it is a must. Recent research points the way.

My article about the gut-brain connection in Alzheimer's disease, and the protective role that fibre could play in this dreaded condition, sparked some lively discussion and some excellent questions.

Given that dementia (including Alzheimer's disease) is now the second leading cause of death in Australia, and the leading cause for women, the lives of all my readers are going to be touched by it in some way.

I figured it's high time, therefore, to survey some other (relatively) recent studies on the prevention and early treatment of dementia.

To help you develop your own dementia prevention plan, I've dividing the research findings into 'dos' and 'don'ts'. Part 1 will cover the don'ts, just to get the negative stuff dealt with first, and Part 2 will do the dos (but not like Betty Boo).

Let's launch into the Don't list:

1. Don't use combined hormone replacement therapy (HRT) pills and patches

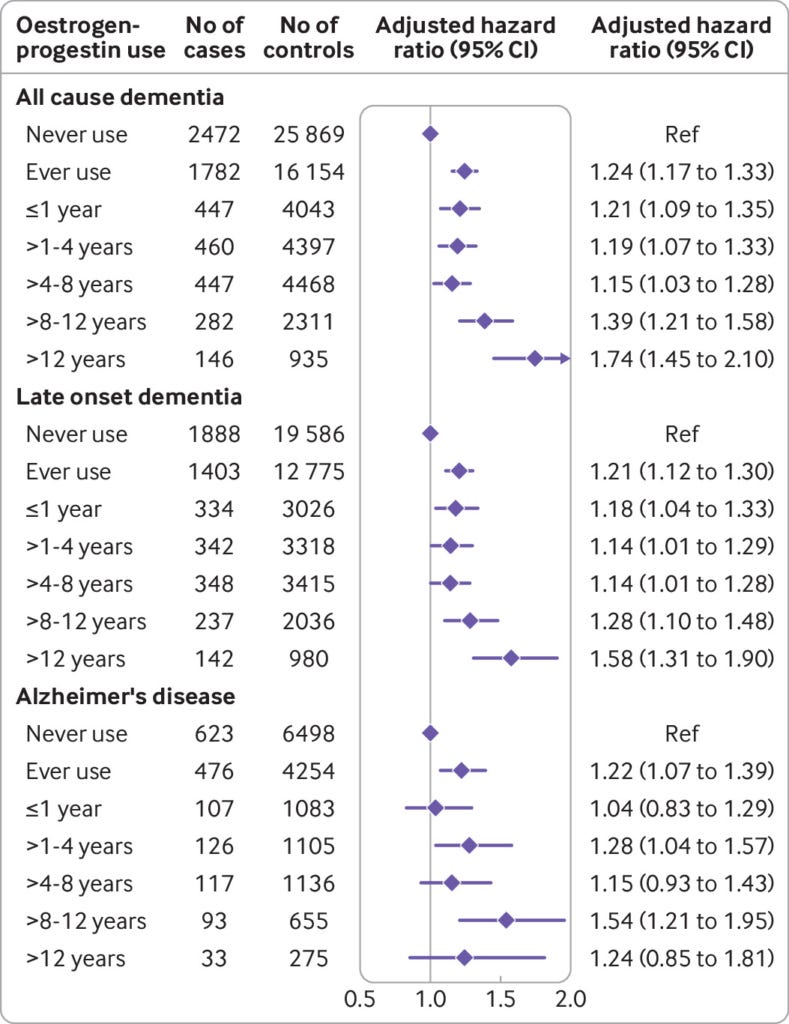

A long-term follow-up study of Danish women has found that any use of menopausal oestrogen-progestin therapy increased the risk of dementia (all types combined) by nearly one quarter, with longer duration of use associated with greater risk.

The study used national registries which essentially cover the entire Danish population. From these registries, the researchers identified all women aged between 50 and 60 on 1 January 2000, who had no history of dementia, breast cancer, gynaecological cancers, thrombosis, liver disease, thrombophilia, bilateral oophorectomy (surgical removal of ovaries), or hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus).

Then they identified women who were diagnosed with any form of dementia between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2018, by scanning the National Registry of Patients for diagnostic codes pertaining to the various subtypes of dementia, and the National Prescription Registry for dementia-specific drug prescriptions. Each dementia patient was matched with 10 female controls of the same age, who did not have a dementia diagnosis.

And finally, they searched the National Prescription Registry for menopausal hormone prescriptions, for both dementia patients and matched controls.

Here's what their analysis of these data revealed:

Women who had ever used menopausal oestrogen-progestin treatment were 24 per cent more like to develop dementia (all types combined) than women who had never used menopausal oestrogen-progestin therapy, or had only ever used systemic or vaginal oestrogen only treatment, or perimenopausal progestin only therapy.

Women who had ever used menopausal oestrogen-progestin treatment were 21 per cent more like to be diagnosed with late onset dementia, and 22 per cent more likely to be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, than never-uses or uses of oestrogen-only or progestin-only therapy.

Risk of all cause dementia increased with longer durations of use, ranging from 21 per cent higher risk for one year or less of use to 74 per cent higher risk for more than 12 years of use.

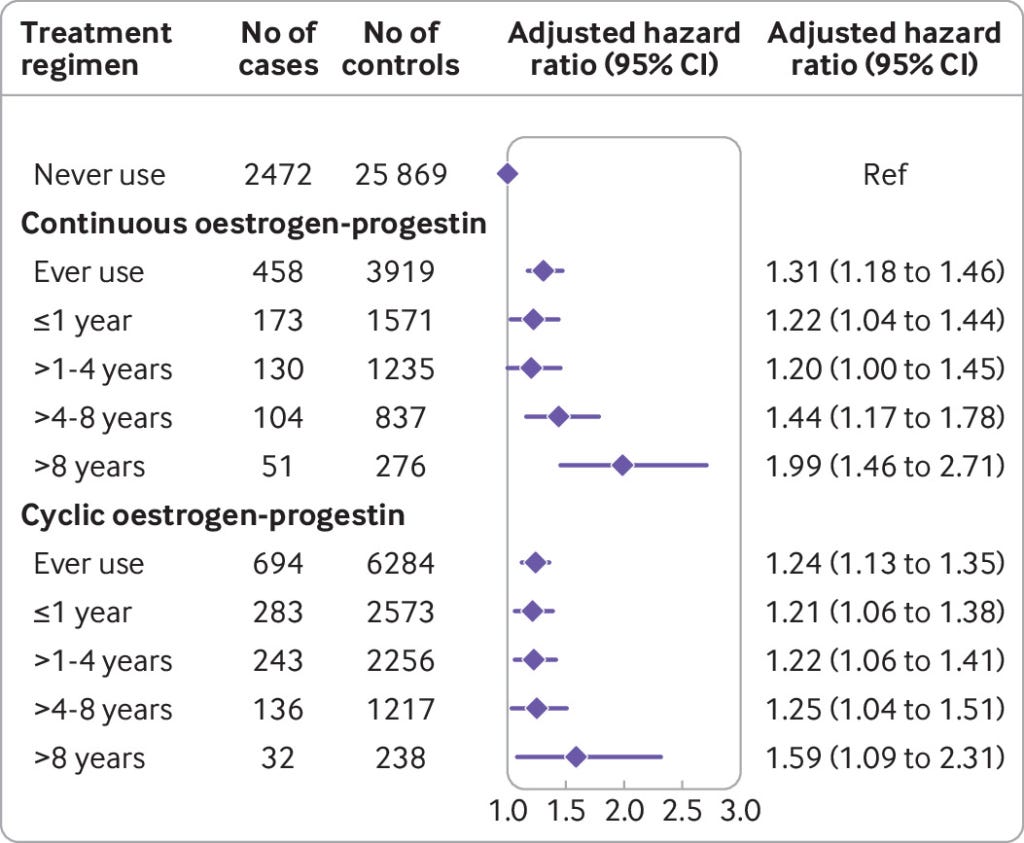

There was no significant difference in risk for continuous vs cyclic regimens of menopausal oestrogen-progestin therapy.

Confining analysis to women who only received combined menopausal hormone therapy at age 55 years or younger did not abolish the association with an increased rate of all cause dementia:

No statistically significant association was found for either progestin only therapy or vaginal oestrogen only treatment for either all cause dementia, late onset dementia or Alzheimer’s disease.

The authors compared their findings with those of other published studies, noting that the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study reported an increased risk of dementia in postmenopausal women treated with oestrogen and progestin after one year of use, while brain MRI scans of a subset of that trial population showed an association between menopausal hormone therapy and brain atrophy, which is a hallmark of cognitive decline and dementia. On the other hand, studies which have concluded that menopausal hormone therapy protects against dementia, suffer from classification errors which call their findings into question.

The authors conclude that even brief use of oestrogen-progestin hormone therapy in women in the early phase of their menopausal transition - the pattern of usage currently advocated in clinical practice guidelines, including the one issued by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists1 - increases the risk of developing the leading cause of death in Australian women:

"Exposure to menopausal hormone therapy was positively associated with development of all cause dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, even for short term usage around the age of menopause onset".

Menopausal hormone therapy and dementia: nationwide, nested case-control study

Action step: If you're a woman approaching the age of menopause, or already undergoing the menopausal transition, commit to diet and lifestyle changes that reduce your risk of suffering bothersome vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes/flashes and night sweats) and other distressing symptoms of menopause, so that you don't need to resort to HRT for relief.

Luckily for you, the same strength training that reduces the risk of dementia (which we'll discuss in Part 2) also reduces the risk of vasomotor symptoms.

2. Don't overdo the coffee

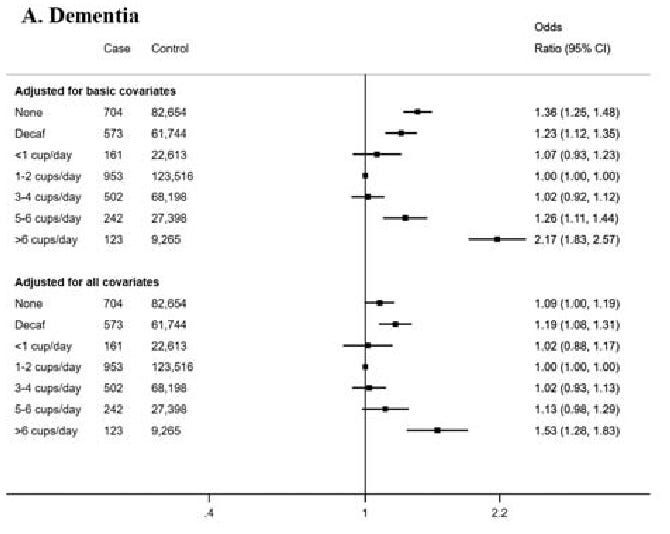

A study drawing on UK Biobank - a large-scale biomedical database and research resource, containing in-depth genetic and health information from half a million UK participants - found that participants who drank more than six cups of coffee a day had a 53 per cent increased risk of dementia compared to those who drank 1-2 cups per day.

In addition, there was a linear inverse association between coffee consumption and total brain volume (measured by magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]), as well as grey matter, white matter, and hippocampal volumes. In other words, the more cups of coffee per day, the smaller the brain.

Non-coffee drinkers and drinkers of decaffeinated coffee had slightly higher odds of dementia.

The researchers listed several mechanisms via which high coffee consumption could decrease brain volume and increase dementia risk, including competitive binding of caffeine to adenosine receptors in the brain (which are involved in the control of circadian rhythms, sleep homeostasis and some neuro-immunological mechanisms), and adverse effects on blood lipids.

Action step: If you're routinely consuming more than 6 cups of coffee per day, you need to cut down, pronto! Green tea, black tea and herbal teas make good substitutes if you're after a hot beverage, but good old water (filtered, to remove the neurotoxic fluoride, of course) should be your primary beverage.

3. Don't be a lazybones, especially as you get older.

In a study of 1646 older adults from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging who were dementia-free at baseline, people who did not have the APOE ε4 gene variant (which substantially increases the risk of cognitive decline and dementia) were almost twice as likely to develop dementia over the 5-year follow-up period if they did not exercise, compared to regular exercisers.

Individuals aged 65 years and older were recruited from 36 urban and rural areas from all 10 Canadian provinces in 1991-1992, and underwent tests of cognitive function as well as assessment of physical activity levels.

Five years later, surviving participants who were cognitively normal at baseline were reassessed, and blood samples were taken for APOE genotyping.

Among those who were not APOE ε4 carriers (i.e. not at genetically increased risk of dementia), the odds of developing dementia were higher in non-exercisers than exercisers (odds ratio, or OR = 1.98; 'odds ratio' is the odds that an outcome will occur given a particular exposure - in this case, lack of exercise - compared to the odds of the outcome occurring in the absence of that exposure). The odds of developing dementia were significantly greater in APOE ε4 allele carriers than non-carriers (OR = 2.02).

As the authors noted, the degree of excess risk of dementia imposed by sedentariness was comparable to the risk from having the APOE ε4 gene variant.

Unfortunately, exercise did not have a protective effect against the development of dementia in APOE ε4 carriers, in this study. You need a comprehensive diet and lifestyle dementia prevention plan, which we'll discuss in Part 2.

Action step: This one is fairly obvious - get off your rear end and move, every day. All forms of physical activity are beneficial; the best form of exercise is the one that you will actually do, on a regular basis.

Next week's post will cover the 'dos' for reducing the risk of cognitive decline and dementia.

For information on my private practice, please visit Empower Total Health. I am a Certified Lifestyle Medicine Practitioner, with an ND, GDCouns, BHSc(Hons) and Fellowship of the Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine.

That's the same body that states that "pregnant women are a priority group for COVID-19 vaccination and should be routinely offered Pfizer mRNA vaccine (Cominarty) [or Moderna (Spikevax) in Australia] at any stage of pregnancy", so you might want to take all their recommendations with a giant handful of salt.

So with only 3 weeks' use of the OCP when I was 20, NO coffee, reasonable activity level, plenty of fruits & vegetables, I shouldn't have too high a risk of dementia. Plus none of my family members had anything more than a little forgetfulness in their late 70s/early 80s.

Guess I'll see how I go, eh?! ;-)

In regards to the coffee study, can it be that as people begin experiencing memory loss, they turn to drinking more coffee as a response because it helps them feel more alert, or they hope it will? I feel this study has bean concocted:-)