Your brain on pain

How your brain 'remembers' pain and inflammation, and what you can do to rewire it

I've written a fair bit about pain and its treatment over the years (see Inflammation: why you’re fat, sick, tired, depressed and in pain… and what to do about it, The surprising – and disturbing – effects of paracetamol on your mind, The placebo paradox and Where is your emotional pain showing up?), and for good reason - chronic pain is quite shockingly prevalent, and highly costly both economically and psychosocially.

According to Painaustralia, which describes itself as "the national peak body working to improve the quality of life of people living with pain, their families and carers, and to minimise the social and economic burden of pain", "3.37 million Australians were living with chronic pain in 2020", or roughly 13 per cent of the population. Chronic pain prevalence is higher in women than in men, and increases with age; compared to working-aged individuals, almost twice as many people aged over 65 suffer chronic pain.

Chronic pain cost this nation an estimated $144.10 billion in 2020, "comprising:

$12.64 billion in health system costs;

$49.74 billion in productivity losses;

$68.63 billion in reduction of quality of life costs and

$13.09 billion in other financial costs, such as informal care, aids and modifications and deadweight losses."

One in five visits to a GP in Australia involve chronic pain, and the majority of these consultations result in a prescription for medication. 72 per cent of people living in rural locales who see a GP for chronic pain will leave with a prescription, compared to 68 per cent of those in regional areas and 65 per cent in metropolitan areas. More often than not, that prescription is for an opioid drug; anti-inflammatories, antidepressants, sleep medications and anticonvulsants are also commonly prescribed. Yet long-term medication use is not effective for chronic pain.

Moreover, using anti-inflammatories for relief of acute pain increases the likelihood of developing chronic pain. And chronic opioid use makes pain worse, in two major ways:

Firstly, opioid drugs disrupt the function of the brain's reward system. This reward system involves, but is not limited to, our endogenous opioid system, which orchestrates the release of endorphins when we engage in pleasurable activities. Endorphins amplify feelings of well-being, and block pain. A person with an opioid-damaged reward system not only feels pain more intensely, but is impaired in their ability to experience pleasure, which mitigates pain. (Think about how much less intense pain feels while you're watching an uproariously funny movie, or losing yourself in an uplifting piece of music.)

And secondly, opioids interfere with the role played by the endogenous opioid system in social bonding. Healthy relationships buffer our resilience to stress, and to pain. By impairing our ability to bond with others, opioids exacerbate social isolation which can not only both heighten and perpetuate physical pain from other sources, but also generates pain - pain that the sufferer perceives as genuinely physical pain - all on its own.

The pain of life

If you're surprised to learn that social pain feels exactly like physical pain, here's the thing you need to understand about pain: In a very real sense, pain is all in your head. Or more precisely, it's all in your brain:

"Pain is not felt in the part of the body that (apparently) ‘hurts’. As Professor Lorimer Moseley, a clinical scientist investigating pain in humans, explains, all pain is produced in the brain, as a result of its processing of multiple, complex stimuli including input from nociceptors (nerve endings that detect tissue damage), its interpretation of the likelihood of damage, and the social, cognitive and affective (emotional) context of the person experiencing the pain.

And as it turns out, some of the regions of the brain that process physical pain – that is, the response to the threat of physical injury – including the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and anterior insula, are also involved in the perception of psychological pain – that is, the response to the threat of social or emotional hurt, such as social rejection or loss of a loved one."

The surprising – and disturbing – effects of paracetamol on your mind

While acute pain mostly occurs in the context of tissue damage - cuts, burns, bruises, sprains, fractures, acute lack of oxygen and the like - most chronic pain is not an indicator of ongoing tissue damage1. Instead, it's driven by maladaptive changes in the central nervous system, psychological factors such as the tendency to ruminate and catastrophise, and behavioural changes which persist long after the resolution of the tissue damage that initially triggered the onset of pain.

It's important to stress that nothing that I've stated so far is meant to imply that people suffering from chronic pain are 'making it up', malingering or even somatising (expressing a mental state, such as anxiety or depression in physical symptoms). Instead, it's more accurate to think of chronic pain as a dysfunctional pattern of response that has become 'wired in' to the person's nervous system and behavioural repertoire.

The brain remembers inflammation

Intriguingly, we now have preliminary evidence that a similar 'wiring in' occurs with inflammation. The memory of an inflammatory episode in a particular part of the body appears to become encoded in a very precise region of the brain, and when this region is triggered, the inflammation flares up again in the exact same location as before.

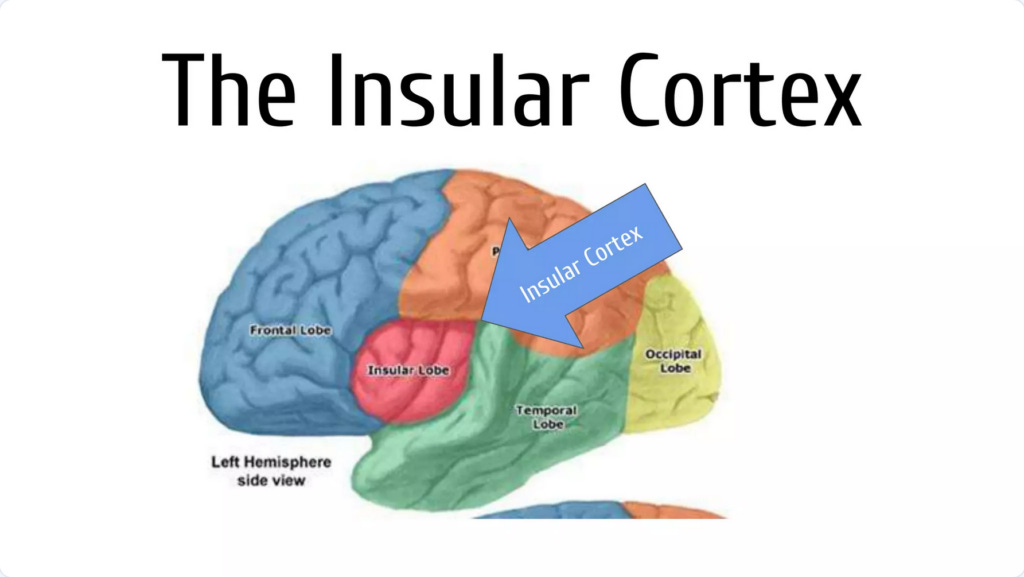

Specifically, a region of the brain called the insular cortex, or simply the insula, is responsible for interoception - that is, the perception of the entire body's physiological state, including temperature, hunger and fullness, heart rate, blood pressure, and inflammation.

The insula is highly connected with the brain's emotional centre, the hippocampus, and the prefrontal cortex, which controls higher-order cognitive functions such as working memory, decision-making, emotion regulation, and self-awareness.

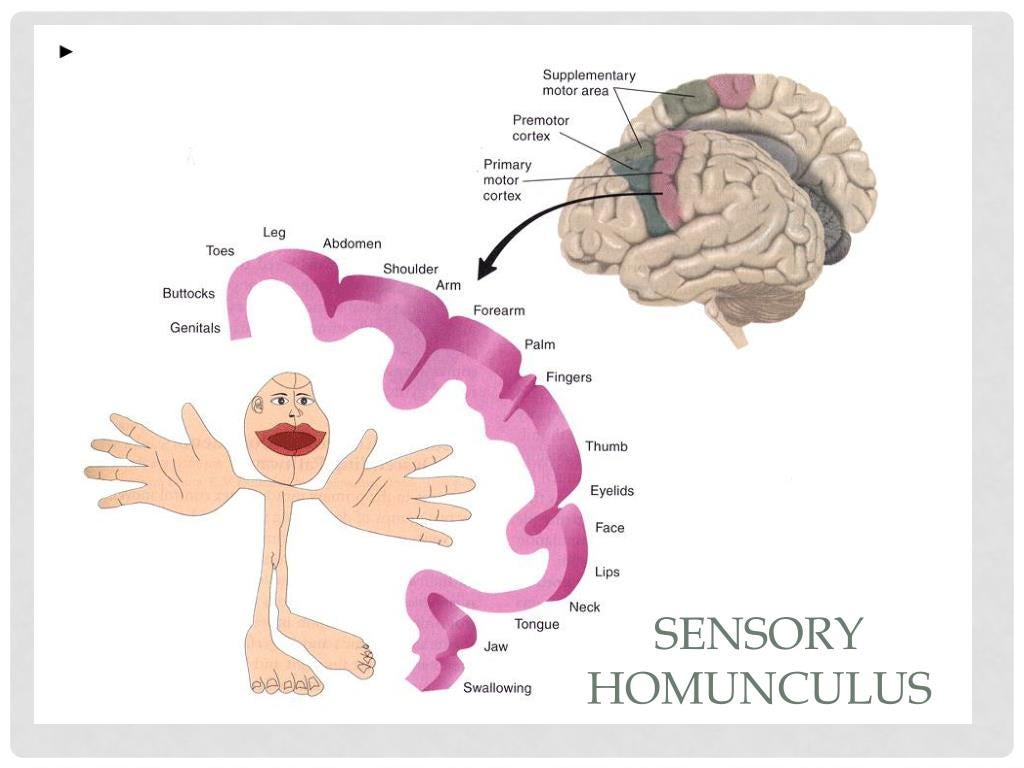

Every part of the body has a direct communication path with a specific set of neurons - dubbed an ensemble - within the insula. Think of this as the insula containing a sensory 'map' of the entire body, rather like the cortical sensory homunculus that you might have seen before:

In experiments performed on mice (which I will not describe in detail as I believe animal experimentation to be deeply unethical) researchers used damaging chemicals to deliberately induce inflammation in the animals' colon and peritoneum. They injected a fluorescent compound that 'lit up' the neuronal ensembles that showed increased activation during the inflammatory episode. Then, when the mice had fully recovered, the researchers artificially stimulated these neuronal ensembles and, lo and behold, inflammation re-emerged in the exact same regions of the colon and peritoneum that had originally been damaged by the chemicals.

And here's something intriguing: the researchers measured blood levels of the stress hormones corticosterone and noradrenaline when they 'switched on' the neuronal ensembles that encoded the memory of the inflammatory episode, and there was no increase in either hormone. So the reactivation of inflammation occurred in the absence of a classical stress response2.

Conversely, when the activity of these neuronal ensembles was suppressed in the midst of a bout of chemical-induced inflammation, the intensity of the inflammatory response was rapidly dialled down, with reduced numbers of white blood cell subtypes that play pivotal roles in that response.

Interestingly, when the researchers gave some of the animals the analgaesic drug acetaminophen (also known as paracetamol), they found that the absence of pain altered, but did not entirely abolish, the immune experience encoded by the brain. So pain plays an important role in this immune encoding, but it's not the be-all and end-all.

To be sure, this is just one study, conducted on mice, and we don't know how well it translates to human beings. But it raises intriguing questions, and if confirmed, has far-reaching clinical implications:

"A fundamental question is the nature of the evolutionary advantage for the organism in encoding such detailed and specific immune information. One possibility is that the brain, which constantly records external cues (e.g., place and odor), also records its own response to these experiences as a means to enable a more effective, anticipatory immune reaction to recurring stimuli. Nevertheless, such a potentially beneficial physiological response could also lead to maladaptive conditions. For example, it was shown almost 150 years ago that presenting patients allergic to pollen with an artificial flower is sufficient to induce an allergic response (Mackeszie, 1886). Moreover, many gut-related disorders are suggested to be psychosomatic in etiology, induced by emotionally salient experiences. The limited understanding of the underlying mechanisms of such disorders (Dinan and Cryan, 2017; Enck et al., 2016; Moloney et al., 2015) hampers the effectiveness of clinical interventions that are currently available. Our findings reveal the potential of inhibiting InsCtx [insular cortex] activity as a means of suppressing peripheral inflammation. Thus, this study adds another perspective to the understanding of these pathological conditions and, presumably, an avenue for therapeutic intervention."

Insular cortex neurons encode and retrieve specific immune responses

Let's unpack that. As a practitioner who specialises in autoimmune conditions, I've long observed that people whose rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease or psoriasis was in remission, are liable to have a flare-up when they experience severe or protracted stress. What if these flares are not caused solely, or even at all, by stress hormones, but instead by the cueing of immunological memories encoded in specific neuronal ensembles, by current distressing events? And what if the food sensitivities that are often experienced by people with autoimmune conditions, are also immunologically encoded in the brain? This would imply that rather than putting these suffering individuals on highly restrictive diets in order to avoid their food triggers (which often seem to multiply like mushrooms), we could help them rewire their brains to disarm those triggers.

We already have a potential model for an intervention of this nature: gut-directed hypnotherapy, which has been shown to be as effective at relieving gastrointestinal symptoms in people with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) as the low-FODMAP diet... with the huge advantage that it doesn't impose dietary restrictions, doesn't deplete beneficial gut bacteria, and its benefits are durable in responders, lasting at least five years after undergoing a course of treatment. I've been referring my IBS clients to the gut-directed hypnotherapy app, Nerva, for several years, and have been mightily impressed by the results3.

The Matrix, reloaded

There's another intervention that I've been using with great success for over twenty years, which may address the encoding of pain and inflammation in the brain: Matrix Reimprinting, a version of Emotional Freedom Techniques, or EFT. During a Matrix Reimprinting session, the client works through a memory that evokes distress, by imagining themselves as they are now, going back into the past to assist and support their 'younger self' who experienced the traumatic incident. The client is instructed to maintain their observer perspective throughout the session, and to interact with that younger self as if with a completely separate person. In some instances, the client might strategically intervene in the memory to alter the outcome; in others, they simply provide resources to help their younger self cope with and learn from the incident. The practitioner guides the client to tune into their younger self and provide them with exactly what they need in order to reach resolution.

After a Matrix Reimprinting session, clients reliably report feeling marked shifts in their feelings and thoughts about the memory. Even the most harrowing memory evokes far less negative emotions, along with enhanced understanding of the behaviour and motives of the other people involved in the remembered incident, and very often, acceptance and forgiveness of themselves and others. They also invariably remark that they see it differently when they attempt to recall it; some describe it as seeming to be very far away, or blurry, or in black-and-white rather than vivid colour, while others find it difficult to recall at all. And the subsequent impact on their physical symptoms is often profound: less pain and muscle tension, dramatically reduced gut symptoms and better sleep.

Research on how the brain processes memories reveals that different regions of the brain are activated when we recall memories as if we were seeing them through our own eyes, versus when we adopt a third-person, or observer perspective. When we recall memories as if seeing them from an observer perspective, there is less activation of the insula than when reliving the memory from a first-person perspective. As you might imagine from the previous description of the role of the insula, what this leads to is a far less 'embodied' reaction to the memory. Furthermore, every time we recall a memory, the process of recalling itself changes aspects of the memory, in particular its emotional signature:

"The emotional intensity of a memory is determined, at least in part, by the way in which you, the rememberer, go about remembering the episode. And the emotions that you attribute to the past may sometimes arise from the way in which you set out to retrieve the memory in the present.”

In other words, if you intentionally retrieve a distressing memory from a third-person perspective, you will feel less emotionally disturbed by it, and as a consequence, you won't view that incident as being nearly so terrible as you would if you recalled it as though seeing it through your own eyes. When you subsequently recall that incident, its emotional valence will be dialled down because of the way you remembered it last time. And all of this is encoded in your brain, including in the insula which connects memories to physiological responses.

Does Matrix Reimprinting change the way that memories are encoded? My clinical observations suggest that it does, although I don't have access to a fancy fMRI machine to prove it! (If any of my readers know of a researcher who would be interested in facilitating this project, drop me a line.)

Here's what I can say for sure: the medical approach to pain, inflammation and chronic illness in general, is completely ass-backwards. Pain is not a disease; it's a signalling system intended to protect us from harm. Inflammation isn't a disorder; it's an attempt to restore order. People who live with chronic pain don't need better pain-killers or more potent anti-inflammatories; they need guidance to understand why they're inflamed and in pain, and a comprehensive program to address the underlying drivers of their condition. And if that program does not include a component that effectively addresses the encoding of pain and inflammation within the brain, it is likely doomed to failure.

For information on my private practice, please visit Empower Total Health. I am a Certified Lifestyle Medicine Practitioner, with an ND, GDCouns, BHSc(Hons) and Fellowship of the Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine.

One notable exception is osteoarthritis, in which ongoing tissue damage does cause persistent stimulation of nociceptors.

Increased inflammation is an integral part of the classical stress response, in order to prepare the body for possible injury.

Roughly 20 per cent of people are non-responders to gut-directed hypnotherapy, but there's absolutely no down-side to trying it if you have IBS, which is a truly miserable condition.

Many years ago I read a book called The Gift of Pain. Whilst quite biblical, it was written by a doctor and his observations of people who suffer from leprosy. Which is quite a weird disease but I seem to recall that loss of “touch” is the only sense that will ultimately kill you.