The good news about depression – Part 1

What you put in your mouth can affect your risk of becoming depressed.

As I wrote in last week’s post, The latest depressing news on antidepressant drugs, antidepressant medications aren’t any more effective than placebo, cause horrendous withdrawal effects in many people, and come with a laundry list of adverse effects which can reduce the ability of depressed individuals to recover, such as sexual dysfunction and reduced physical movement. But yeah, apart from that…

Depression has probably always been a part of the human experience. The biblical Book of Job, for instance, according to two medical writers, “discloses a modern scientifically accurate description of a depression that, at times, was life-threatening”.

However, whereas historically most people suffered a bout of depression, then spontaneously recovered and did not become depressed again, since the advent of antidepressant medications, depression has been transformed into a chronic and disabling illness.

In a world where a far lower proportion of humans than at any time in our species' history live in abject poverty, bury multiple children before they reach puberty, suffer the loss of their wives to childbirth or their husbands to warfare, or experience any of the other devastating life events that you’d figure might trigger a bout of depression, more of us are depressed than ever before.

For example, a survey of over 250 000 Europeans found that 6.4 per cent met the diagnostic criteria for a depressive disorder, with four times higher rates of depression in the most economically developed countries than the least developed (although within countries, those with the lowest monthly incomes had a substantially higher rate of depression than the highest earners).

This study analysed survey data gathered in 2013-15, long before COVID policies made people’s lives even more miserable. All that pointless biosecurity theatre didn’t just drive up inflation, food shortages, small business bankruptcies and family conflicts, whilst failing to save a single life, it also jacked up rates of psychological conditions, including depression.

For example, a meta-analysis of 29 studies that included over 80 000 young people (aged under 18) from around the globe, found that 25 per cent of children and adolescents had clinically elevated symptoms of depression and 20 per cent, of anxiety – double the prepandemic rates of these conditions. Girls and older adolescents were the worst affected, and studies which collected data later in the manufactured crisis found higher prevalence of anxiety and depression than those conducted earlier.

In Australia, the number of children and adolescents admitted to intensive care units (ICU) for treatment of deliberate self-harm (such as self-injury or self-poisoning) rose dramatically during the time of maximal government-imposed restrictions, from 7.2 admissions per million children in March 2020 to 11.4 admissions per million children by August 2020. Meanwhile, all-cause paediatric ICU admissions fell from a long-term monthly median of 150.9 per million to 91.7 per million in April 2020. In other words, COVID wasn’t landing kids in ICUs, but self-harm caused by the impact of government policies – such as stay-at-home orders; closure of schools, playgrounds and entertainment venues; and draconian restrictions on social activity – was.

Kids weren’t the only ones suffering increased rates of depression as a direct result not of a virus with an infection fatality rate in the same ballpark as a bad seasonal flu, but of massive government interference in their lives. A meta-analysis of 12 community-based studies conducted in the early months of the manufactured COVID crisis (when non-evidence-based lockdown policies were imposed on the bulk of the world’s population), and involving over 30 000 people from Asia, India, Europe and the UK, found a prevalence rate of 25 per cent for depression. The authors compared this to a global estimated prevalence of depression of 3.44% in 2017, noting that the prevalence of depression had shot up seven-fold from prepandemic levels.

Just in case you were wondering, depression doesn’t just increase your risk of ending up in an ICU because you’ve attempted to poison or hang yourself. You’re 40% more likely to develop heart disease or have a stroke if you’re depressed, according to a study of over 12 000 Chinese adults.

Well, all of that is pretty depressing. Where’s that good news that I promised in the title of this article? I’m so glad you asked. The good news is that there is – quite literally, if you were to print out all the pages of published studies – tonnes of research on the interventions that help depressed people make a lasting recovery and return to living fulfilling, productive lives.

Many of those interventions also help people who are experiencing heightened anxiety, noting that symptoms that were attributed to “anxiety” in the 1950s and 60s were redefined as indicators of depression in the 1970s-90s, and are now on their way to being moved back into the bucket of anxiety symptoms.

(In other words, the diagnostic criteria for so-called anxiety disorders and mood disorders are a movable feast, shifting from one diagnostic category to another depending on social trends and the prevailing fashions in research and drug development. The former director of the National Institute of Mental Health, Thomas Insel, commented that the diagnostic criteria used by psychiatrists to assign a label to your particular brand of distress suffer from a “lack of validity”, which, to put bluntly, means that they’re pretty much made up by whomever holds sway at the time.)

Over the next few weeks, I’ll be running through some of the latest research on the best-studied and most effective ways to reduce psychological distress, whether you want to call it depression, anxiety, or just the human condition. Part 1 will be focused on the diet-depression link.

Diet and depression: Eat your dang fruits and vegetables

I’ve discussed the research demonstrating a clear and causal relationship between what you put in your mouth and your psychological well-being in a whole slew of previous articles, including Eat your way to better mental health?, Good mood food, The evidence is in: Eating better relieves depression, Want to feel happier? Change what’s on your plate! and Beat the holiday season blues – with broccoli and berries!

If you haven’t already read those articles, here’s the quick take: Eating crap makes you feel like crap, while eating more healthy, minimally processed plant foods – especially fruits and vegetables – is associated with a reduced risk of developing depression, better odds of recovering from depression, better mood and greater psychological flourishing.

And if you have read them, there’s nothing new under the sun in the latest research, just more reinforcement to do what your granny told you, and eat your dang fruits and vegetables (and mushrooms).

But reinforcement of healthy habits is a good thing, so here goes:

Study #1 - Prevalence and variability of current depressive disorder in 27 European countries: a population-based study

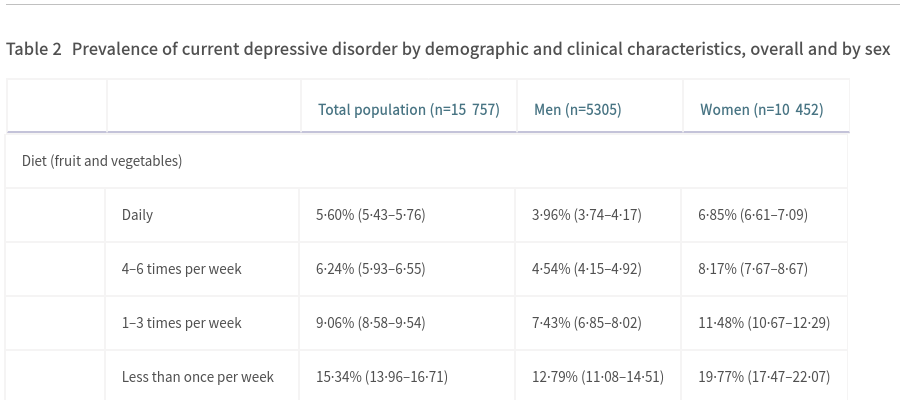

Remember that survey of over 250 000 Europeans that found that 6.4 per cent of them were depressed? It turns out that the researchers asked participants a lot of questions, and one of them related to their fruit and vegetable intake.

Good thing they did, because the relationship between current depression and fresh produce intake was strong, and dose-dependant. People who ate fruits and vegetables less than once per week – around 3 per cent of surveyed men, and 1.65 per cent of women – were around three times more likely to fulfil the diagnostic criteria for depression than those who ate them daily:

Study #2 - Nutritional Factors, Physical Health and Immigrant Status Are Associated with Anxiety Disorders among Middle-Aged and Older Adults: Findings from Baseline Data of The Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA)

This study, involving nearly 27 000 middle-aged and older native-born and immigrant Canadians enrolled in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging, found that those who ate fewer than three serves of fruits and vegetables per day had about a 25 per cent higher risk of reporting a physician-diagnosed anxiety disorder than those who ate 6 or more serves per day.

Eating between a half and 2 servings of pulses (legumes) per day was also associated with a reduced risk of being anxious, although the effect size was not as large.

Higher body fat percentage was also associated with an increased risk of currently having an anxiety disorder, and other research demonstrates that those who eat more fruits and vegetables and legumes have a lower risk of excessive body fatness.

Those who ate pastries every day had a startling 55 per cent higher risk of having an anxiety disorder than those who reported never eating pastries. So for anxious Annies, the best dietary advice is to hold the Danish and pass the kale and lentil salad.

Study #3 - Depression in middle and older adulthood: The role of immigration, nutrition, and other determinants of health in the Canadian longitudinal study on aging

The same Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging found that consuming fewer than 2 serves of fruits and vegetables per day was associated with a 33 per cent higher risk of current depression than eating 6 or more servings per day.

In bad news for chocaholics, those who ate chocolate bars were more likely to be depressed, with those eating less than 0.6 of a chocolate bar per week (seriously, who eats 0.6 of a chocolate bar?) having a roughly 15 per cent higher risk of current depression than those who never ate them, while men who ate more than 0.6 of a chocolate bar per week had a 72 per cent higher risk and women, a 66 per cent higher risk.

Study #4 - Mushroom intake and depression: A population-based study using data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2005–2016

Why should fruits and vegetables get all the credit, when eating mushrooms can turn you from a sad man to a fun guy (fungi, geddit???)?

Researchers examined data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2016, finding that only 5.2 per cent of the almost 25 000 participants ate mushrooms (what the heck is wrong with these people?), but those who ate modest amounts (median intake of 4.9 g/d) had 69 per cent lower odds of current depression.

The researchers speculated that mushrooms’ high content of ergothioneine – a potent antioxidant that crosses the blood-brain barrier and has been shown to relieve depression symptoms in an animal model – may play a key role in the observed effects.

They also point out that mushrooms are high in prebiotics (compounds that promote the growth of beneficial gut bacteria) including fibre-associated monosaccharides, chitin, and β-glucans.

And that’s highly relevant to our discussion, because a particular pattern of gut microbiota perturbation has been found not just in major depressive disorder and anxiety but also bipolar disorder, psychosis and schizophrenia. This pattern involves depletion of anti-inflammatory bacteria that require prebiotics (carbohydrates found only in plant foods and fungi) in order to produce the short chain fatty acid butyrate, and enrichment of pro-inflammatory bacteria which thrive in the guts of people on low-fibre diets.

Study #5 - Plant-based dietary quality and depressive symptoms in Australian vegans and vegetarians: a cross-sectional study

Who eats the most plant foods? Vegetarians and vegans! However, whereas in the past those who ate a plant-exclusive diet had no choice but to eat healthy plant foods (fruits, vegetables, grains, legumes, nuts and seeds), there’s now a plethora of highly-processed vegan junk foods to titillate their palates. As a consequence, researchers now distinguish between high-quality and low-quality plant-based diets.

In a study of 219 Australian adults following vegetarian and vegan diets, a high-quality plant-based diet was found to be protective against the development of depression. The authors noted that sales of packaged vegan food in Australia are projected to reach approximately $A215 million. They cautioned that the proliferation of these foodless foods comprised of ultra-processed ingredients such as refined vegetable oils, sugar, refined grains and salt, may mislead individuals who mistakenly believe that plant-based diets are intrinsically healthy, into consuming a low-quality diet that increases their risk of depression.

Summary:

A plant-forward diet that particularly emphasises fruits, vegetables, mushrooms and legumes is strongly protective against the development of depression and anxiety. To reduce their risk of becoming depressed, vegans and vegetarians need to be aware that a plant-based diet is not necessarily health-promoting, and ensure that they’re choosing a diet high in nutritional quality rather than filling up on highly processed “cruelty-free” versions of the crap they used to eat before they stopped eating animals.

Stay tuned for Part 2, tentatively titled “Get off your dang backside, put that stoopid phone down and go outside”.

I remember a couple of palliative nurses said that whatever we consume we will pay for them in the later life.

Smiles Trial. Moderate intake of meat good for moderate to severe depression. Run by nutritional psychiatrist Felice Jacka.

https://foodandmoodcentre.com.au/smiles-trial/

Women who don't eat enough red meat is linked to depression.

https://www.deakin.edu.au/research/research-news-and-publications/articles/women-should-eat-red-meat#:~:text=It's%20good%20mood%20food%20says,depression%20and%20anxiety%20in%20women.

Preview of studies revealing link between vegetarianism and greater risk of depression.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/au/blog/animals-and-us/201812/the-baffling-connection-between-vegetarianism-and-depression

But there is evidence linking traditional mediterranean diets low in red meat with a reduced risk of depression.