Hard on the heels of Dr Dean Ornish's groundbreaking randomised controlled trial demonstrating that early-stage Alzheimer's disease can be reversed with comprehensive diet and lifestyle changes, comes the publication of a new study on what it takes to become a centenarian.

And just as Ornish's work demonstrates that engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviours can actually allow people's brains to recover from neurodegeneration, restoring their capacity to interact with their loved ones, pursue their hobbies and independently perform the activities of daily living, the new study identifies the three daily actions to take (or not take) if you want to maximise your chances of hitting the ton.

Want to know what those three powerful actions are? Patience, young grasshopper.

We'll get to that, soon enough. But first, let's dig into the study.

Researchers based in the US and China used a case-control study design to analyse data from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS), a nationally representative cohort of people aged 80 years or older, which is "the world's largest survey on centenarians, nonagenarians and octogenarians".

The CLHLS was established in 1998, prompted by the Chinese government's concern that their nation's rapid socioeconomic development was leading to greater chances of survival at every age, and hence to longer life expectancy, which inevitably leads to dramatic expansion of the aging population. Elderly people don't contribute to the economy through employment (at least not directly, although they may provide indirect economic benefits such as caring for grandchildren so that parents can work), and the cost of providing medical and residential care for them is a serious concern for wealthy, industrialised countries, let alone economically transitioning countries like China. Consequently, the Chinese government decided to invest in research to uncover the factors associated with healthy aging, in hopes that - ahem - encouraging their citizens to engage in health-promoting behaviours, and disincentivising unhealthy ones, could reduce the economic burden of their burgeoning elderly population.

And in typical Chinese fashion, the researchers didn't mess around: the CLHLS "randomly sampled half of the counties and cities in 22 of the 31 provinces in mainland China, covering approximately 85% of the total population". Repeat surveys have been conducted every two to three years since 1998, with each subsequent survey following up previously-enrolled participants and recruiting new ones.

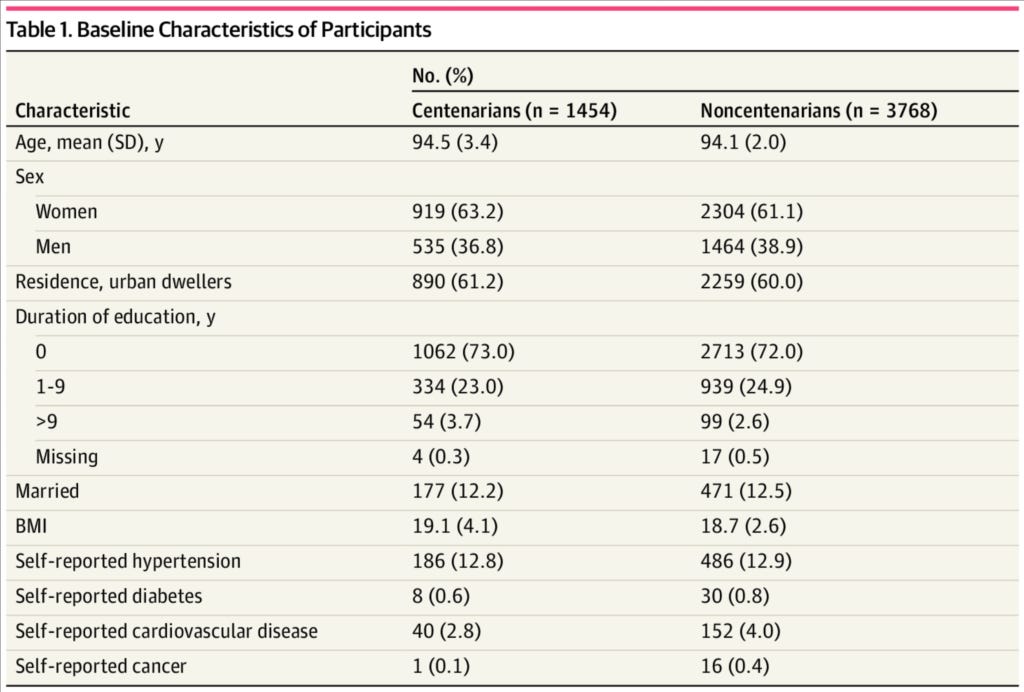

Out of this vast database, researchers identified 17 917 participants aged 80 years or older, who entered the cohort between 1998 and 2008 and had the potential (mathematically speaking) to live to 100 years or older by 2018. After weeding out participants who were lost to follow-up or had incomplete information on required lifestyle factors at baseline, they were left with 1454 participants who had become centenarians. Each centenarian was matched by sex, entry year, and age (± one year) at the year of entry with three other participants who had died before reaching the age of 100 - a total of 3768 noncentarians.

Then the researchers combed through the questionnaire responses and records of physical examinations of their 5222 participants, to assign each one a healthy lifestyle score (HLS) comprising five components: smoking status, alcohol use, exercise, dietary diversity (more on that shortly), and body mass index (BMI).

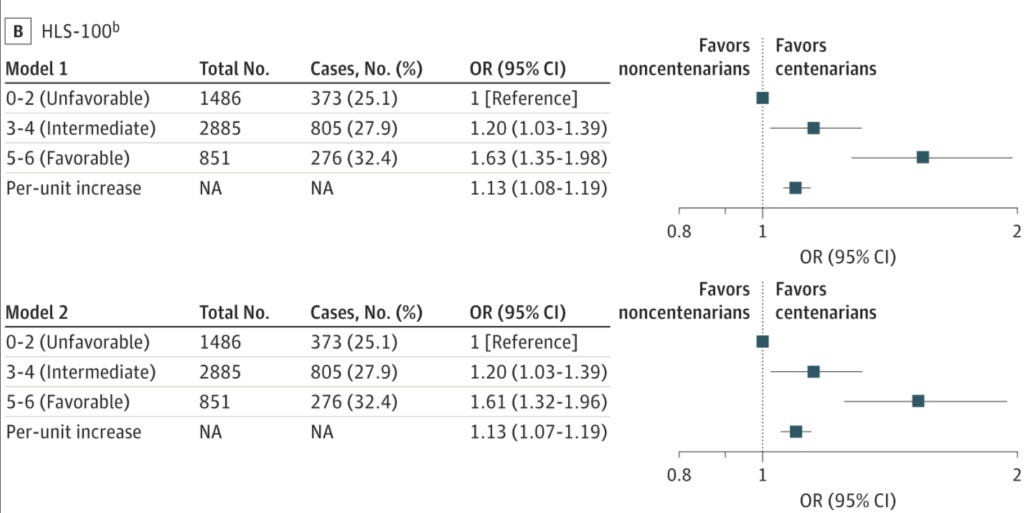

Primary analysis of the data revealed that neither alcohol consumption nor BMI were predictive of living to 100 or beyond if you had already survived to 80, so the researchers constructed a new version of the HLS tailored for adults aged 80 years or older: the HLS for 100 (HLS-100), which excluded these two components.

Several sensitivity analyses - that is, further explorations of the role that each healthy lifestyle behaviour played in increasing the chances of living to 100 or beyond - were conducted. These included deleting one factor at a time from the model to see if its absence affected the outcome, and defining the outcome as not merely becoming a centenarian, but doing so in good health (i.e. with "no self-reported chronic conditions, normal physical and cognitive function, and good mental wellness").

After turning the data inside out, upside down and back to front, nine ways to Sunday, the researchers were pretty confident that they had correctly identified the three most robust predictors of living until 100 or beyond if you've already made it to 80, with roughly 60 per cent higher odds of doing so for those with the highest attainable scores in each healthy lifestyle domain:

And they were (drumroll please):

Having never been a smoker

Exercising regularly

Having greater dietary diversity.

Unfortunately, "greater dietary diversity" was not defined in the paper itself; one has to delve into the Supplement to find out more:

"Dietary intake was evaluated based on a food frequency questionnaire, and dietary diversity was assessed according to the frequency of consuming five food groups: fruits, vegetables, fish, beans, and tea. Participants reported 'almost every day,' 'except winter or sometimes or occasionally,' or 'rarely or never.' for the intake frequency of each food group, and were assigned scores of 2, 1, or 0 accordingly, generating a total dietary diversity score ranged from 0 to 10. We then classified scores of 7-10 as favorable (2 points), 4-6 as intermediate (1 point), and 0-3 as unfavorable (0 point) for inclusion in the healthy lifestyle score calculation."

eMethods. Detailed Methods; Assessment of individual lifestyle factors; from 'Healthy Lifestyle and the Likelihood of Becoming a Centenarian'

It would have been interesting to see how intake of the other food groups which were assessed in a previous study of the CLHLS cohort, 'Dietary diversity and cognitive function among elderly people: A population-based study', impacted on the chances of becoming a centenarian. This paper measured frequency of consumption of vegetables, fruits, legumes and their products, nuts, meat, eggs, fish, milk and dairy products, and tea, and found that reduced dietary diversity (i.e. lower frequency of intake of any of these food groups) was correlated with poorer cognitive function in the elderly Chinese population. Because this was a cross-sectional study, the researchers were not able to determine whether poorer cognitive function (and the poorer general health that accompanies it, for example reduced mobility and capacity to cook meals, and impairments to chewing and swallowing) was driving reduced dietary diversity, or vice versa.

Also, no substitution analyses were conducted in this study, to tease out the effect of, for example, swapping legumes for meat, or fish for eggs. Some studies conducted in Western populations provide useful background:

In the Nurses' Health Study, conducted on a cohort of US females aged over 60, substituting plant proteins for dairy and other animal proteins was associated with better odds of healthy aging, absence of physical function limitations and good mental status, and lower risk of frailty.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies analysed 37 publications based on 24 cohorts, and found that substituting healthy plant foods such as legumes, nuts and whole grains for animal foods was associated with decreased risk of cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and all-cause mortality. In particular, replacing red meat with nuts and whole grains, replacing processed meat with nuts and legumes, replacing dairy foods with nuts, and replacing eggs with nuts and legumes, were all associated with a reduced risk of all-cause mortality.

Analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease study (2019) suggests that "a sustained change from the typical Western diet to an optimal diet rich in legumes, whole grains, and nuts with reduced red and processed meats" would extend life expectancy by over 8 years if adopted at age 60.

A study of long-term associations between low carbohydrate diets, low fat diets and mortality in middle-aged and older people found that, overall, low carbohydrate diets were associated with increased total and cause-specific mortality (although healthy low carbohydrate diets, characterised by reduced saturated fat intake, yielded a marginally significant five per cent lower total mortality). Conversely, those who ate the healthiest version of a low-fat diet, characterised by high intake of unrefined carbohydrates, had 18 per cent lower total mortality,16 per cent lower cardiovascular mortality, and 18 per cent lower cancer mortality.

The Chinese study produced some unexpected findings. In particular, there is a well-established relationship between higher income and education levels and greater life expectancy in Western countries, including the US, UK and Australia, where wealthier and better-educated people can expect to live up to 25 per cent longer lives than the poorest and least-educated.

Studies conducted in Western populations also show that married people live longer than unmarried people. And one would logically expect that poor cardiometabolic health (high blood pressure, diabetes and cardiovascular disease) would reduce one's chances of reaching 100. So it's interesting that in the Chinese cohort, "No significant differences were detected between cases (centenarians) and controls (noncentenarians) regarding their sociodemographic characteristics and medical conditions":

I'm just speculating here, but my best guess is that this cohort of elderly Chinese hit the demographic transition jackpot: they grew up in a China which was much poorer than Western countries, necessitating physical (and largely agricultural) work, an unprocessed diet and self-propelled transport; they reached maturity well before the Great Leap Forward of 1960–1962, which precipitated a disastrous famine in which between 30 and 45 million Chinese people died of starvation, execution, torture, forced labour, and suicide; and had children (and probably, grandchildren) decades before the One Child Policy was instituted in 1979, providing for plenty of practical and emotional support from their own offspring in their old age, given the emphasis in Chinese culture on respecting and caring for one's elders. And now, as they reach their ninth decade and beyond, China is an upper-middle income country with some means to provide for its seniors.

UPDATE

A reader suggested another potential contributing factor to longevity in this cohort - the absence of air and water pollution during the first several decades of their lives:

How well these findings map onto Western populations, which have been overfed, oversized and underexercised for many decades, is of course open to question. But the consistency with which abstinence from smoking, being physically active and eating a diverse and nutritious diet is linked with greater longevity, and (even more importantly, in my opinion) with healthy aging, in diverse populations, does increase confidence that these are not random associations, but truly causal factors.

And finally, this study provides encouragement for those who are wondering if they've left it too late to adopt longevity-promoting habits. You're never too old to benefit from upping your game when it comes to diet and lifestyle:

"By targeting the older age group (≥80 years), this observed association between a higher HLS [healthy lifestyle score] and a higher likelihood of becoming a centenarian extended our understanding that people with healthy lifestyle behaviors, even at a very advanced age, could still have better health outcomes compared with their counterparts."

Healthy Lifestyle and the Likelihood of Becoming a Centenarian

This post has taken me approximately 15 hours to research and write. I make all my posts freely available to all readers, because I believe we all deserve access to information that helps us to take greater control over our health. But I rely on my small core of paid subscribers to provide this service to those who genuinely can’t afford it.

Very informative and I would agree with your best guesses about the cohort, perhaps add that their air and water was much cleaner prior to the recent rapid industrialisation.

Thanks Robyn. Very interesting