In Part 1 of this mini-series on preventing the second-leading cause of death in Australia, and the leading cause of death in women, I summarised some recent research findings on the 'don'ts': don't use combined menopausal hormone therapy, don't overdo it on coffee, and don't be sedentary.

Now let's talk about the 'dos':

1. Do take a comprehensive diet and lifestyle approach to dementia prevention

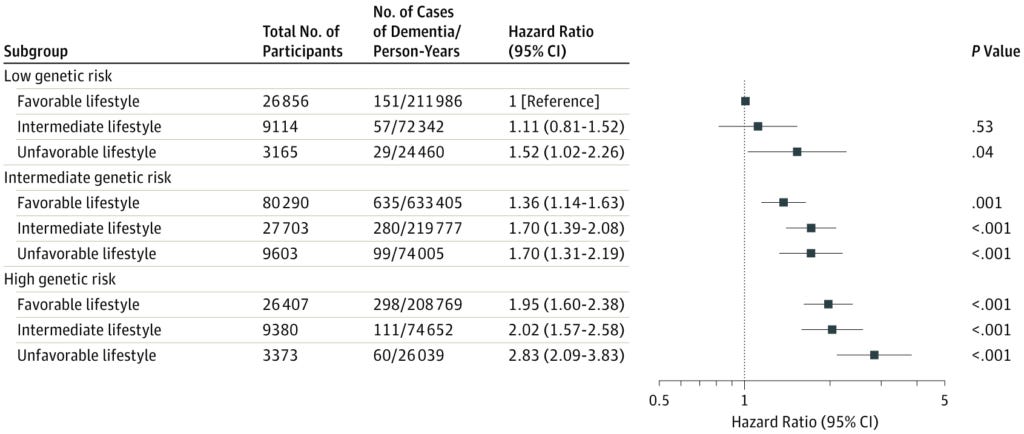

A study of over 196 000 older adults enrolled in UK Biobank (the same biomedical database and research resource that unearthed the connection between excess coffee intake and dementia risk that I mentioned in Part 1) found that adherence to four healthy lifestyle factors reduced the risk of developing dementia, in people at both high and low genetic risk.

The study, 'Association of Lifestyle and Genetic Risk With Incidence of Dementia', was a retrospective cohort analysis of UK Biobank participants of European ancestry, who were aged over 60 and free of cognitive impairment at the time of their enrolment (between 2006 and 2010), and for whom genetic information was available. The average follow-up period was eight years.

Participants were sorted into five groups ('quintiles'), from low to high genetic risk for dementia, based on a polygenic risk score that included the APOE ε4 gene variant (which we discussed in Part 1 in relation to physical inactivity and dementia risk) and several other gene variants known to be associated with the risk of late-onset Alzheimer's disease in people of European ancestry.

A healthy lifestyle score was developed, based on adherence to just four factors:

No current smoking;

Regular physical activity (defined as ≥150 minutes of moderate activity per week OR ≥ 75 minutes of vigorous activity per week OR an equivalent combination OR moderate physical activity at least 5 days a week or vigorous activity once a week);

Healthy diet, defined as at least 4 of the following 7 food groups:

Fruits: ≥ 3 servings/day

Vegetables: ≥ 3 servings/day

Fish: ≥2 servings/week

Processed meats: ≤ 1 serving/week

Unprocessed red meats: ≤ 1.5 servings/week

Whole grains: ≥ 3 servings/day

Refined grains: ≤1.5 servings/day; and

Moderate alcohol consumption (defined as up to 1 standard drink per day for women and up to 2 standard drinks per day for men.

I consider this a fairly lax definition of 'healthy lifestyle', which is no doubt why a full 68.1 per cent of participants were assessed as adherent to a favourable lifestyle, based on their responses to questionnaires. Only 8.2 per cent fell in the 'unfavourable lifestyle' bracket, while the remaining 23.6 per cent were classified as following an 'intermediate lifestyle'.

But even using these pretty half-arsed criteria, the differences in dementia risk between those with the lowest vs highest healthy lifestyle scores were quite stark:

Comparing those at low genetic risk, those with the most unfavourable lifestyle had a 1.5-fold higher risk of developing dementia within the follow-up period of the study than those with the most favourable lifestyle.

Those at high genetic risk, and with the most favourable lifestyle, still had almost double the risk of developing dementia as the low genetic risk, favourable lifestyle group.

But those at highest genetic risk who followed the most unfavourable lifestyle almost tripled their chances of developing dementia (hazard ratio [HR] 2.83) compared to low-risk, healthy-living people.

Just think how much more you could ratchet down your risk of becoming cognitively impaired in later life, if you adopted a really healthy lifestyle, including:

A nutrient-dense plant-slant diet with an emphasis on green leafy vegetables and berries;

Strength training to increase and then maintain your lean mass (see Do #2 below, and my previous articles Strong body, healthy brain and Crossword puzzles or pumping iron – what’s best for maintaining your marbles?);

Maintaining healthy blood pressure throughout life (see Do #3 below);

Sleep optimisation;

Active stress management (see Do #4 below);

'Brain exercise' via intellectual challenges and meaningful social interaction; and

Addressing environmental factors that impair brain health (see Memory Makeover by Dr Wes Youngberg for an in-depth discussion of this topic).

Action step: Take an honest inventory of your current diet and lifestyle habits. Keep a food journal for one week, writing down everything you eat and drink. Track your physical activity for a week: how many hours do you spend sitting, standing, doing active tasks (e.g. gardening, housework), and exercising? How much sleep do you get each night, and do you wake refreshed in the morning? How much do you challenge and stimulate your brain by, for example, learning a new language, playing a musical instrument, playing strategy games such as chess or bridge, learning complex dance routines, writing, and engaging in civilised debates with people who don't share your views (not Twitter flame wars!!!!)? Do you have a de-stressing or downshifting routine? How much time do you spend outdoors, in nature vs indoors, in artificial lighting? Your responses to this self-quiz will help you identify the lifestyle domains that require the most attention. Feel free to reach out to me if you need guidance or coaching to shed your bad habits and replace them with healthy lifestyle practices.

2. Do build and maintain strong muscles, all through your life

A study of over 450 000 participants in the UK Biobank, and a further 324 000 participants in two other studies, found that people with a genetic predisposition to higher lean mass (i.e. more muscle) had a lower risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Those with the highest lean mass in their arms and legs also demonstrated better cognitive performance than their scrawnier brethren.

The study authors identified 584 gene variants that, in combination, explained just over 10 per cent of the variance between individuals in appendicular lean mass (that is, muscle mass in the arms and legs), as measured by bioimpedance. None of these gene variants were located within the APOE gene region, which is associated with vulnerability to Alzheimer's disease. The occurrence of these gene variants, in aggregate, was used as a proxy for lean mass.

Each one standard deviation (a measure of the amount of variance in a set of statistical values) increase in genetically proxied appendicular lean mass was associated with a 12 per cent lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease. This association between more lean mass and reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease was replicated using a different method of measuring lean muscle mass, which incorporated the trunk and whole body. Genetically proxied lean mass was also associated with better cognitive performance, measured by standard intelligence testing.

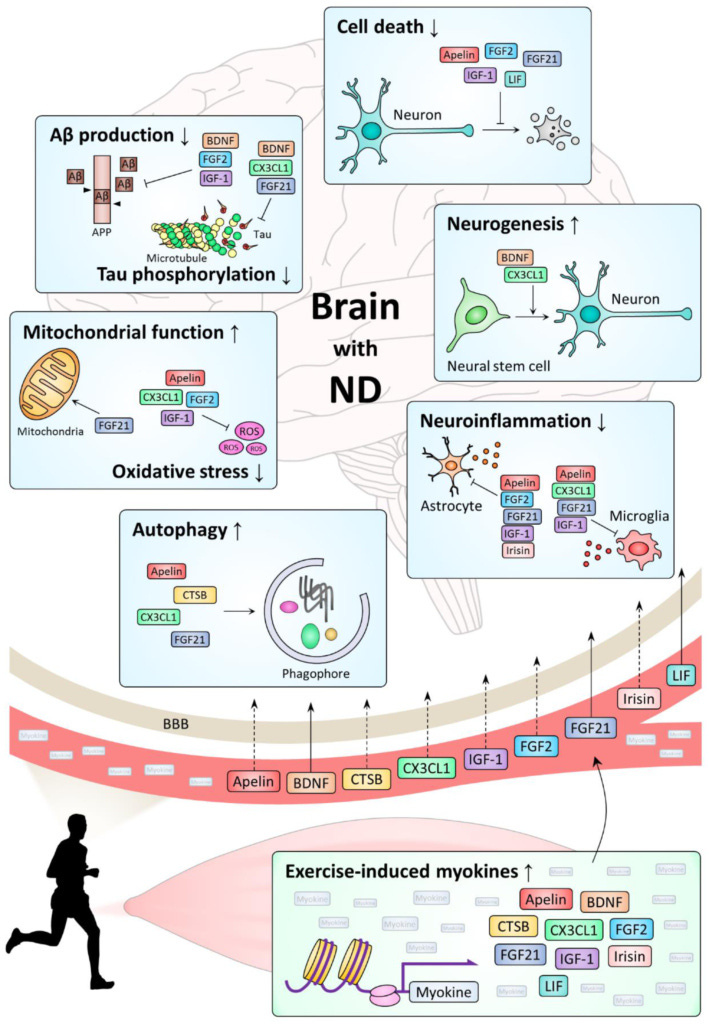

The researchers speculated that the link between greater muscle mass and lower risk of Alzheimer's disease might be mediated by the protective effect of lean tissue against insulin resistance and/or high blood pressure (both risk factors for dementia), or by myokines - peptides (short proteins) produced and secreted by skeletal muscles during exercise.

Multiple myokines, including brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), cathepsin B (CTSB) and fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), have been found to have neuroprotective effects, and to suppress neuroinflammation (one of the principle drivers of dementia and other neurodegenerative diseases).

The authors acknowledge the limitations of their study, and call for further research to confirm their findings, identify whether they also apply to other forms of dementia, explore the mechanisms by which higher muscle mass protects against Alzheimer's and - perhaps most importantly - determine whether exercise interventions early in the course of cognitive decline might stave off the development of full-blown Alzheimer's.

However, they also express confidence that their findings cannot be explained away by confounding or reverse causality, and hold the promise for an important modality of preventive care to reduce the burden of Alzheimer's disease on individuals, families and society:

"These analyses provide new evidence supporting a cause-and-effect relation between lean mass and risk of Alzheimer’s disease... In this study, we identified genetic support for a protective effect of lean mass on the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and on higher cognitive performance. Further investigation is warranted to understand the clinical and public health implications of these findings."

Genetically proxied lean mass and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: mendelian randomisation study

Neither general activities like housework and gardening, nor cardiovascular exercise such as walking, running and aerobics classes, are sufficient to build and maintain lean mass, especially as we age.

Dedicated strength training, using bodyweight exercises (push-ups, chin-ups, pull-ups), free weights (dumbbells, barbells, kettlebells, sandbags), weights machines or resistance bands, is an absolute necessity if you wish to stave off sarcopaenia - the age-related progressive loss of muscle mass and strength that is a major cause of disability, institutionalisation in nursing homes, and premature death.

This new study adds reduced risk of Alzheimer's disease to the growing list of benefits of developing and maintaining a strong body throughout the lifespan.

Both males and females should ideally be incorporating at least two dedicated strength training sessions per week into their activity schedule, from at least their early 20s, to attain the highest peak lean mass that is genetically possible for them, and then maintain it throughout their lives. But even for those commencing resistance training late in life, impressive gains in muscle size and strength, mobility, stamina and energy metabolism are possible with sufficient training volume.

'Gentle exercise for seniors' classes just don't cut it - oldies need to lift weights that are heavy enough to challenge them, and increase the weight progressively as their strength and stamina improve.

Action step: Include at least two dedicated strength training sessions per week into your schedule. Consult an exercise physiologist who specialises in strength training for older people if you've never lifted weights before, or have an injury that limits mobility.

3. Do ensure you maintain a healthy blood pressure - not too high, not too low - throughout your life

Most people are aware that having high blood pressure (hypertension) is a health hazard, but it's less well known that having blood pressure that is too low (hypotension) in later life is also dangerous.

In a long-term follow-up study of over 4700 US women, compared to participants who had normal blood pressure in both midlife and late life, both having high blood pressure in midlife and late life, and having high blood pressure in midlife but low blood pressure in late life, increased the risk of being diagnosed with dementia.

The study enrolled women who were aged between 45 and 65 in 1987 to 1989. In a series of follow-up visits over the next two and half decades, the women underwent various tests, including blood pressure measurements, a cognitive battery and functional assessments. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure above 140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure above 90 mm. Hypotension was defined as a systolic blood pressure lower than 90 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure lower than 60 mm Hg.

After 24 years of follow-up, it was found that women who were hypertensive in both midlife and late life had a 49 per cent higher risk of being diagnosed with dementia than participants who had normal blood pressure in both life phases, whilst those who had hypertension in midlife but developed hypotension in late life had a 62 per cent higher risk.

This is not the first study to find a heightened risk of dementia with late life hypotension. A population-based health study of over 24 000 Norwegians found that

"Over the age of 60 years, consistent inverse associations were observed between systolic blood pressure and all-cause dementia, mixed Alzheimer/vascular dementia, and Alzheimer disease, but not with vascular dementia, when adjusting for age, sex, education, and other relevant covariates."

Why, you might ask, does having low blood pressure in late life carry a greater risk of developing dementia than having high blood pressure at this time? Quite simply, because low blood pressure decreases blood flow to the brain when an individual is sitting or standing, and diminished blood flow is believed to play a critical role in the development of dementia and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Researchers at Binghamton University in New York have found that diastolic blood pressure is the better predictor of cognitive performance. In a yet-to-be-published study of the relationship between blood pressure and cognitive performance, they found that over 85 per cent of otherwise healthy 50-95-year-old subjects had resting diastolic blood pressures below 80 mm Hg, and that three quarters of those with below normal blood pressure also scored below normal in tests of cognitive function.

These researchers also noted that the most common cause of low blood pressure is low cardiac output (insufficient blood pumped out by the heart with each stroke), which is due in turn to insufficient blood being returned to the heart from the lower body.

Their previous work has demonstrated the critical role played by the soleus muscles - the 'calf' muscles in the middle of the lower legs - in maintaining normal blood pressure during sedentary activities. The soleus muscles are deep postural muscles that are most active during activities such as sustained squatting or standing on one's toes.

It's interesting to note that squatting is the preferred resting position of hunter gatherer communities like the Hadza of Tanzania. The Hadza spend about as many hours per day as the average Westerner in sedentary positions, but the time they spend in 'active rest' positions like squatting is associated with cardiometabolic benefits, compared to sitting in chairs.

Finally, as I noted in 5 reasons to think twice before taking blood pressure drugs, overly-aggressive treatment with antihypertensive drugs can drive diastolic blood pressure to dangerously (even fatally) low levels:

"An analysis of 22 576 patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease found that the patients whose diastolic blood pressure was lowered to 60-70 mm Hg had almost double the risk of death or nonfatal heart attack or stroke compared to those with a diastolic pressure of 80-90 mm Hg, while those diastolic BP was pushed down to 60 mm Hg or less had triple the risk!"

Action step: Tracking your blood pressure, preferably with a home blood pressure monitor that you use regularly, is a vital element in taking control of your health. If you are over 60, currently on antihypertensive medication, and your diastolic blood pressure is regularly below 80 mm Hg, talk to your prescribing doctor about reducing the dose to prevent diastolic hypotension... and work on your hunter gatherer squat!

If you're hypotensive without medication, you too will benefit from activating your soleus (and other postural muscles) by developing your capacity to hold that squat. Toe standing can also be practised while you're brushing your teeth, washing up or working at a standing desk.

My articles 5 reasons to think twice before taking blood pressure drugs and High blood pressure: When drugs do more harm than good discuss the dangers of antihypertensive medication, while my March 2020 Deep Dive webinar (which you can access by activating your free 1-month trial of my EmpowerEd membership program) presented a comprehensive lifestyle medicine treatment program for hypertension.

4. Do put your body into 'rest and restore mode' every day

As we age, the activity of the parasympathetic branch of our autonomic nervous system declines, while sympathetic nerve activity increases. Decreased heart rate variability (HRV) is a primary indicator of reduced parasympathetic activity, while circulating noradrenaline levels are a marker of increased sympathetic activity.

This sympathetic dominance is associated with known risk factors for Alzheimer's disease, including sleep disorders, diabetes, and heart disease. Furthermore, chronically elevated stress is associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer's disease, and overproduction of noradrenaline accelerates the spread of the signature pathologies of Alzheimer's disease in the brain.

In a small study of healthy adults (54 young, and 54 older adults), participants were randomised to use either slow-paced breathing and a biosensor device (the emWave Pro), to increase their heart rate variability (remember, this signifies increased parasympathetic activity, or to use biofeedback to decrease their heart rate variability (signifying increased sympathetic activity, aka a more stressed state).

Slow-paced breathing combined with biofeedback to increase heart rate variability led to decreased plasma levels of amyloid beta, a biomarker associated with higher risk of Alzheimer's disease and cardiovascular death, as well as reduced noradrenergic signalling.

While acknowledging that plasma amyloid beta is only a proxy measure of how well the brain is clearing amyloid beta, the study's authors highlighted the fact that theirs is the first behavioural intervention that has been shown to reduce this signature biomarker of Alzheimer's disease.

They also pointed to the positive results of a multi-component clinical trial on 25 patients with dementia or mild cognitive impairment. This pilot study used a closely related biofeedback device intended to increase heart rate variability (HeartMath Inner Balance) as its stress management intervention. Patients experienced improvements in biochemical markers, standardised assessments of everyday function, neuropsychological test scores and even increased brain volume.

It's important to emphasise that the heart rate variability training was just one aspect of this comprehensive approach to treating dementia and its precursor condition, mild cognitive impairment, and hence it's impossible to determine whether, and how much, it contributed to the positive outcomes attained in this pilot study.

Nonetheless, the study offers real hope to patients and their families, who are usually presented with an exceptionally grim prognosis.

The study also underscores the need for a multifaceted approach to this complex condition, which I wholeheartedly endorse.

Action step: Commit to a daily practice of downshifting, destressing or unwinding, that reduces sympathetic nervous system activity and increases parasympathetic activity. If you want to use the intervention employed in the study discussed above, check out the HeartMath website to learn more about this technique, and explore their range of biofeedback devices.

Final note: I have many more articles on preventing dementia, and other pathological conditions of aging, in my Aging & Longevity Article Library. These articles will help you identify problem areas in your current habits of living, and develop a comprehensive diet and lifestyle program to help you maximise physical and mental function as you move through your autumn years.

Great article Robyn. Do you know of any research linking the benefits of fasting or IF in relation to Alzheimer/ dementia ?

All excellent recommendations! Have you read about Dr. Bredesen, he claims to have reversed Alzheimer’s in 9 out of 10 cases. Here is a quote from him:

“People have not known what’s causing this disease, and it’s often said there’s nothing that prevents, reverses, or delays it. Nothing could be further from the truth. We know there are many contributors, [including] anything that damages mitochondria [and] different infections.

Amyloid is an excellent biomarker but a terrible therapeutic target, and that’s exactly what’s coming out of the data. According to conventional thought, elevated tau and beta-amyloid are causative factors in Alzheimer’s, but Dr. Bredesen’s research suggests otherwise. He explains:

“What we now see from the research is that Alzheimer’s disease, fundamentally, is a network insufficiency. You have this beautiful network of about 500 trillion synapses and as you get exposed to inflammation, infections in your mouth, insulin resistance, leaky gut, not enough blood flow, reduced oxygenation, reduced mitochondrial function, any of these things, that network is no longer sufficiently supported.