Back in 2016, I ran a webinar for my EmpowerEd membership group on cancer screening. (You can view this, along with many hundreds of hours of other webinars on all things nutrition- and health-related, by taking advantage of the 1-month free trial of EmpowerEd membership.)

During this webinar, I noted that the first randomised controlled trial of screening colonoscopy for the prevention of colorectal cancer would report its findings in the mid-2020s.

Well, those results have been reported, a little earlier than expected, and they validate the scepticism that I expressed about cancer screening in general during the 2016 webinar:

People who were invited to undergo screening colonoscopy were less likely to be diagnosed with colorectal cancer, but they were not less likely to die from colorectal cancer, nor did they have any lower risk of dying overall.

Now, there are some important nuances to this study, and we’ll get to them. But first, let’s zoom out and ask some higher-order questions about the purpose and value of cancer screening programs in general.

Question 1: What is cancer screening?

Answer: Cancer screening is a systematic attempt to detect cancer before it becomes clinically apparent, in asymptomatic individuals, using laboratory tests, imaging studies or physical examination. Examples include screening mammograms to detect breast cancer, Pap smears to detect cervical cancer, and screening colonoscopy to detect cancer of the bowel and rectum.

Importantly, cancer screening is not the same as a diagnostic test (although the same procedures are used for both screening and diagnosis). People with symptoms – such as a new lump in the breast, or bleeding from the bowel – should see their doctor for appropriate diagnostic testing.

Question 2: What is the intention of cancer screening?

Answer: Screening programs aim to detect cancer at an early stage, on the assumption that it will be more treatable. The intention is to spare the patient from the more aggressive treatments that are used on advanced cancers, and to lower the death rate from that particular cancer.

Question 3: How well does cancer screening work?

Answer: It depends on what you mean by ‘work’!

Cancer screening programs undoubtedly detect more early-stage tumours. However, many, if not most of these small tumours are indolent – that is, they are slow-growing and unlikely to metastasise, or spread to vital organs. Hence, detecting them at an early stage and treating them as cancer won’t save lives, because indolent tumours are highly unlikely to result in death, no matter how long they hang around; in fact, many of them may have spontaneously regressed had they remained undetected.

Meanwhile, screening is very likely to miss truly deadly cancers, which simply grow and spread too fast to be detected by periodic examinations. In fact, the term ‘interval cancers’ was coined to denote aggressive tumours that spring up in the interval between screening tests.

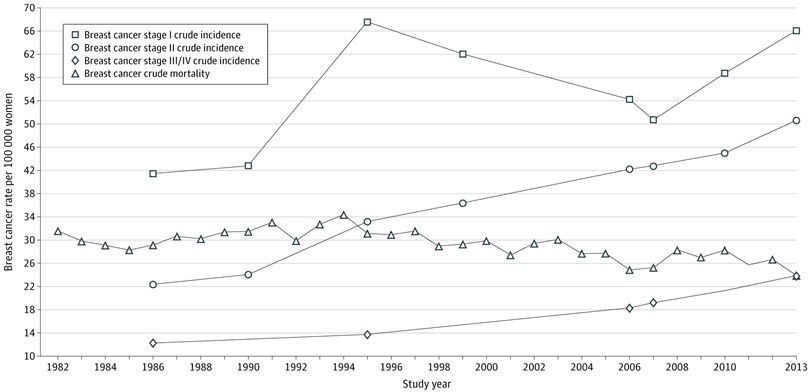

In my previous article, New study on screening mammography shows more harms than benefits, I reproduced the following chart, from an article which examined the impact of a government-funded screening mammography program on the incidence of, and death from, breast cancer in Victoria:

As you’ll notice, the incidence of early stage breast cancers shot up after the federally-funded BreastScreen program was launched in 1991, indicating overdiagnosis (more on that below). However, diagnoses of advanced breast cancer also continued to rise, almost doubling in the two decades after the BreastScreen program began, indicating that it was failing to detect lethal breast cancers at an early stage:

“Crude incidence of advanced stages III/IV breast cancer increased by 96% from 12.2 to 23.9 per 100 000 women from 1986 to 2013, ruling out a direct association of mammographic screening with breast cancer mortality.”

H. Gilbert Welch uses the “barnyard pen of cancers” analogy to characterise the highly heterogeneous grab-bag of diagnoses collectively labelled ‘cancer’, into three types of animal, with the fence representing screening:

‘Birds’ represent the most lethal type of cancer. No fence can contain them; they simply fly away. By the time ‘bird’ cancers are detected, they’ve already spread around the body, invading vital organs. Conventional cancer treatments hold no hope of cure; at best, life may be prolonged by surgery, chemotherapy, radiation or immunotherapy, but at the cost of side-effects that dramatically reduce quality of life.

‘Rabbits’ could be contained if you build enough fences. Catching ‘rabbits’ is the mainstay of cancer screening. This would be worthwhile if ‘rabbit’ cancers would have gone on to cause life-threatening illness if they had not been detected, but research indicates that this is rarely the case. In the small minority of people in whom screening caught a ‘rabbit’ that would have gone on to kill them, detecting it early would only be of benefit if the treatments for that cancer type were effective at curing it, and did not cause harms that outweigh their benefits. By the time we apply all these criteria, we’re in unicorn land.

‘Turtles’ can easily be contained by fencing, but since they weren’t going anywhere anyway, there’s no point in putting the effort into building the fence.

It’s the ‘turtles’ and ‘rabbits’ that are most likely to be detected by cancer screening. Hence, cancer screening results in considerable overdiagnosis – that is, many people are told that they ‘have cancer’, and undergo aggressive treatment which may lead to lifespan-shortening health problems (including, ironically enough, cancer), for a tumour which would never have led to serious illness or death if it had remained undetected. Listen to Welch explain it, clearly and concisely:

Question 4: Are there any harms from cancer screening?

A: Yes, several types:

The screening test itself can result in harms, or can lead to further diagnostic procedures with the potential for harm. For example:

As mentioned in my previous article Preventing bowel cancer, for every 10 000 screening colonoscopies performed, four will result in perforation of the colon and eight in a major intestinal bleeding episode, both of which are potentially fatal.

In another previous article, PSA screening leads to unnecessary treatment… and suffering, I described how ‘routine’ measurement of prostate specific antigen (PSA) frequently results in a referral for prostate biopsy, which carries significant risks including rectal bleeding, blood in the semen, difficulty with passing urine, fever, infection, sexual impairment and decreased libido. In addition, heightened anxiety whilst waiting for the results of the biopsy may prompt prescription of psychoactive medications, bringing a fresh new load of risks into the equation.

Mammograms involve exposure of breast tissue to ionising radiation, which is a known carcinogen. Having biennial mammograms may increase the risk of developing breast cancer, especially in women who are genetically hypersusceptible to radiation-induced cancer.

Overdiagnosis, discussed in the previous section. Overdiagnosis leads to the psychological stress of becoming ‘a cancer patient’ even though you don’t actually have a life-threatening disease, and puts you at risk of treatment-related harms. Given the lack of overall mortality benefit (discussed next), if you are a victim of overdiagnosis, you won’t live any longer, you’ll just live longer with the diagnosis of cancer – that is, if you’re not killed by the unnecessary treatment.

If screening identifies cancer, you will be pressured to undergo cancer treatment which may include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy and/or hormonal therapy. Each of these forms of treatment carries harms which may or may not exceed their benefits for your particular case of cancer.

Getting the ‘all clear’ from a screening test might give you a false sense of security, causing you to become less likely to engage in health-promoting behaviour. This self-licensing effect could end up increasing your risk of developing cancer or other chronic degenerative diseases in future. For example, in the NORCCAP trial which assessed the value of flexible sigmoidoscopy screening for colorectal cancer,

“Three years after screening, attenders were more likely to gain weight and were less likely to stop smoking, engage in physical activity and eat fruit and vegetables compared to a randomly chosen sample from the control group.”

Question 5: Might getting screened for cancer save my life?

A: Given the relentless propaganda campaigns pushing various forms of cancer screening, it may surprise you to learn that cancer screening has never been shown to “save lives”.

Some, but by no means all, randomised controlled trials of cancer screening have found that people who undergo screening are less likely to die from that particular cancer. However, many of the same studies found that overall mortality was higher in the screened group:

According to the authors;

“In five of the 12 trials, differences in the two mortality rates went in opposite directions, suggesting opposite effects of screening. In four of these five trials, disease-specific mortality was lower in the screened group than in the control group, whereas all-cause mortality was the same or higher. In two of the remaining seven trials, the mortality rate differences were in the same direction but their magnitudes were inconsistent; i.e., the difference in all-cause mortality exceeded the disease-specific mortality in the control group. Thus, results of seven of the 12 trials were inconsistent in their direction or magnitude.”

All-Cause Mortality in Randomized Trials of Cancer Screening

The lack of overall mortality benefit is acknowledged even by advocates of screening. For example, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPTSF), which recommends that women aged 50-74 have mammograms every 2 years, found that

“None of the trials nor the combined meta-analysis demonstrated a difference in all-cause mortality with screening mammography.”

Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement

USPTSF also currently (as of 2021) recommends screening for colorectal cancer starting at age 45 years and continuing until age 75 years. But in their 2016 recommendation statement, they admitted that

“To date, no method of screening for colorectal cancer has been shown to reduce all-cause mortality in any age group.”

Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement

One of the screening methods that USPSTF endorses for colorectal cancer is, of course, colonoscopy. And that brings us back (at last!!!) to that recently-published randomised controlled trial of screening colonoscopy. Nearly 85 000 people aged 55 to 64 years, from Poland, Norway, and Sweden, participated in the trial. Roughly one third of participants were invited to undergo a single screening colonoscopy (invited group), while the remaining two thirds received no invitation or screening (usual care group).

0.98 per cent of the people in the invited group were diagnosed with colorectal cancer during the follow-up period (median of ten years), compared to 1.20 per cent of the usual-care group. This is a relative risk reduction of 18 per cent, and an absolute risk reduction of 0.22 per cent. However, there was no statistically significant reduction in the risk of death from colorectal cancer (0.28 per cent in the invited group and 0.31 per cent in the usual-care group), or in all-cause mortality (11 per cent in both groups). 455 people needed to be invited to undergo screening to prevent one case of colorectal cancer.

The researchers were at pains to point out that only 42 per cent of the invited group actually had a colonoscopy, and they estimated that the risk of colorectal cancer would have been reduced by 31 per cent, and the risk of dying of colorectal cancer by 50 per cent, if everyone in the invited group had actually been screened.

Another concern raised by Lancet editorialists is that many of the colonoscopies performed for the trial failed to meet quality benchmarks, suggesting that pre-cancerous tumours may have been missed.

But even if everyone in the invited group had showed up for a colonoscopy, and every colonoscopy had been perfectly performed, the effect on overall mortality would be vanishingly small.

Remember, while 11 per cent of usual-care participants died during follow-up, only 0.31 per cent of them died of colorectal cancer. Not only would screening colonoscopy have had no impact on all these other deaths, it may even have contributed to them through the self-licensing effect described above, in which being given a clean bill of health on cancer screening appeared to disincentivise people to maintain good health habits. What is the gain to you if you’re saved from a grisly death from colorectal cancer at the age of 75, only to die of a heart attack instead because your A-OK on the colonoscopy report lulled you into believing that you could get away with smoking, eating garbage, and being overweight and lazy?

And finally, it’s worth bearing in mind that the colorectal cancers that are most likely to kill you are birds: they’ve already flown away before you get the chance to participate in a screening program of any type:

“Not all colon cancer is biologically similar and amenable to mortality reduction through early detection.”

Blood-Based Screening for Colon Cancer: A Disruptive Innovation or Simply a Disruption?

Why do governments continue to promote cancer screening programs?

Most cancer screening programs fail to achieve their objectives. On the whole, they don’t “catch cancer early, when it’s easier to treat” because aggressive cancers grow and spread too quickly to be detected through periodic screening; they don’t reliably decrease the risk of dying from that particular type of cancer, and they don’t reduce all-cause mortality1. They’re also incredibly expensive. So why do governments still push them so aggressively? There are several contributing factors, including

Inertia: cancer screening programs are now well-entrenched, and have built up a bureaucracy whose primary mission is to perpetuate and expand itself, as was brilliantly satirised in Yes Minister:

Vote-buying: For a politician chasing the ‘woman vote’, flinging extra money at breast cancer screening is a favoured strategy, while funding bowel cancer screening kits earns brownie points (err, pun not intended) with the pensioner lobby.

Catering to interest groups: Medical technology companies, laboratories and doctors are major beneficiaries of government-subsidised screening programs. Pharmaceutical companies also cash in on the additional patients generated by screening. Currying favour with these wealthy interest groups by promoting screening, increases the chances of garnering political donations.

Sheer incompetence: The past three years of ridiculous COVID policy has amply demonstrated that most politicians wouldn’t know a cost-benefit analysis from a cos lettuce.

Rank cowardice and total failure of leadership: Those who do understand why cost-benefit analyses should be run on every single policy they propose or implement are too cowed by fear of electoral backlash if they defund cancer screening programs that the public has been fooled into believing are ‘saving lives’.

What should you do?

Just because cancer screening programs are, on the whole, ineffective at achieving outcomes that really matter to most people – like living longer in good health – doesn’t mean that you’re powerless to protect yourself against this dreaded disease (or, more accurately, this heterogeneous grab-bag of diagnoses that have only the word ‘cancer’ in common with each other).

I have a whole section in my Article Library on cancer, which I strongly urge you to peruse. But since the topic of this article is colorectal cancer, it’s hard to go past the advice of Dr Denis Burkitt, an Irish surgeon and medical researcher who worked in Uganda for several decades (and after whom Burkitt’s lymphoma is named). Observing the stark differences in the incidence of chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, gall bladder disease, hypertension, constipation and colorectal cancer between Africans and his own countrymen, Burkitt concluded that the unrefined, fibre-rich diet eaten in Africa was the key to freedom from these diseases.

Here are some of his most famous sayings:

“Diseases can rarely be eliminated through early diagnosis or good treatment, but prevention can eliminate disease.”

“The only way we are going to reduce disease, is to go backward to the diets and lifestyles of our ancestors.”

“The frying pan you should give to your enemy. Food should not be prepared in fat. Our bodies are adapted to a stone age diet of roots and vegetables.”

and, perhaps my favourite:

“Societies that eat unrefined foods produce large stools and build small hospitals; societies that eat fibre-depleted foods produce small stools and build large hospitals.”

This drawing sums it up perfectly:

Further reading:

Breast cancer screening – when ‘talking to your doctor’ may mislead rather than inform

New study on screening mammography shows more harms than benefits

Prostate cancer: duplicity, deception and betrayal

For information on my private practice, please visit Empower Total Health. I am a Certified Lifestyle Medicine Practitioner, with an ND, GDCouns, BHSc(Hons) and Fellowship of the Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine.

Cervical cancer screening may be an exception, but definitive evidence of all-cause mortality reduction is still lacking.

Another great post Robyn. Many people have so much faith in cancer screening. I've noticed skin screening clinics are also very popular these days and every slight mark on the skin is hailed as being a budding killer melanoma. They give strict instruction to never let direct sunlight fall on your skin and slap on toxic 50+ at the mere thought of going outside, it's lunacy.

Nice. Very nice. In some ways endorses my attitude of not seeing doctor’s because “they might find something”.