Lean body, healthy brain

New research shows that the more muscle mass you have, the sharper your brain... and the more visceral fat mass, the higher your risk of developing dementia.

What mental picture do you conjure up, when you think of elderly people? Do you picture frail, stooped, doddery ‘little old ladies’? Or ‘silly old buggers’ holding up the checkout line because they can’t work the EFTPOS device?

How about when you picture yourself as an elderly person? Do you imagine yourself playing with your grandchildren, travelling the world, and enjoying pastimes you never had time for when you were working full-time and raising your own children?

Or do you see yourself as one of those senescent elderly folk, inexorably sliding into physical and mental decrepitude until, like my late stepfather in the final five years of his life, you wake up each morning wishing that you hadn’t… or like my mother-in-law, who progressively lost her mobility, independence, ability to communicate, memories and her very personhood, in a tortuous ten year descent into the inchoate hell known as vascular dementia?

Although most humans develop a fear of death as soon as we become intellectually capable of grasping what it means, I would argue that most people fear decline – especially a long drawn out period of decline – far more than they fear death itself. Death, after all, is just a moment. Decline can stretch out for decades.

But are we doomed to failing physical and mental powers as we get older? It turns out that the processes that rob bodies of their strength and vigour are inextricably linked to those that rob minds of their sharpness, so, very conveniently, there are common solutions to both problems.

Fat chance of aging well

One of the mental functions that is particularly hard-hit by the normal aging process is fluid intelligence – the capacity to think and reason abstractly, and to come up with novel problem-solving strategies for situations that you’ve never encountered before.

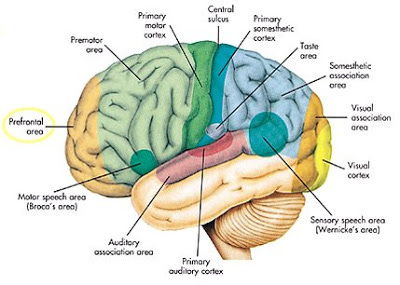

This age-related decline in fluid intelligence is linked to atrophy (shrinkage) in the anterior prefrontal cortex of the brain – the yellow-orange ‘bulge’ at the front of the brain (at left in the diagram below) – and deterioration in the integrity of white matter in the frontal lobe (the areas marked in yellow-orange and pale green below).

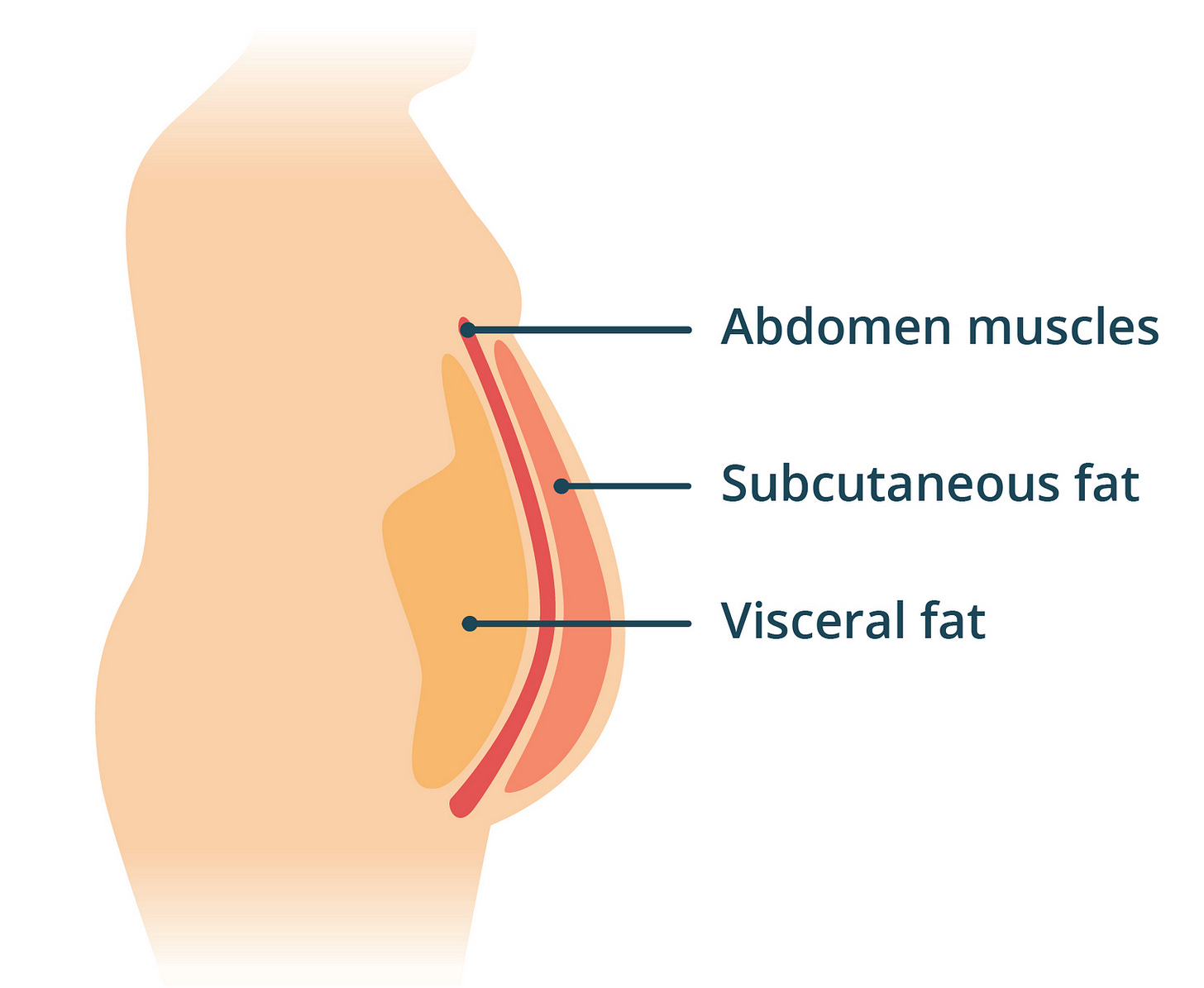

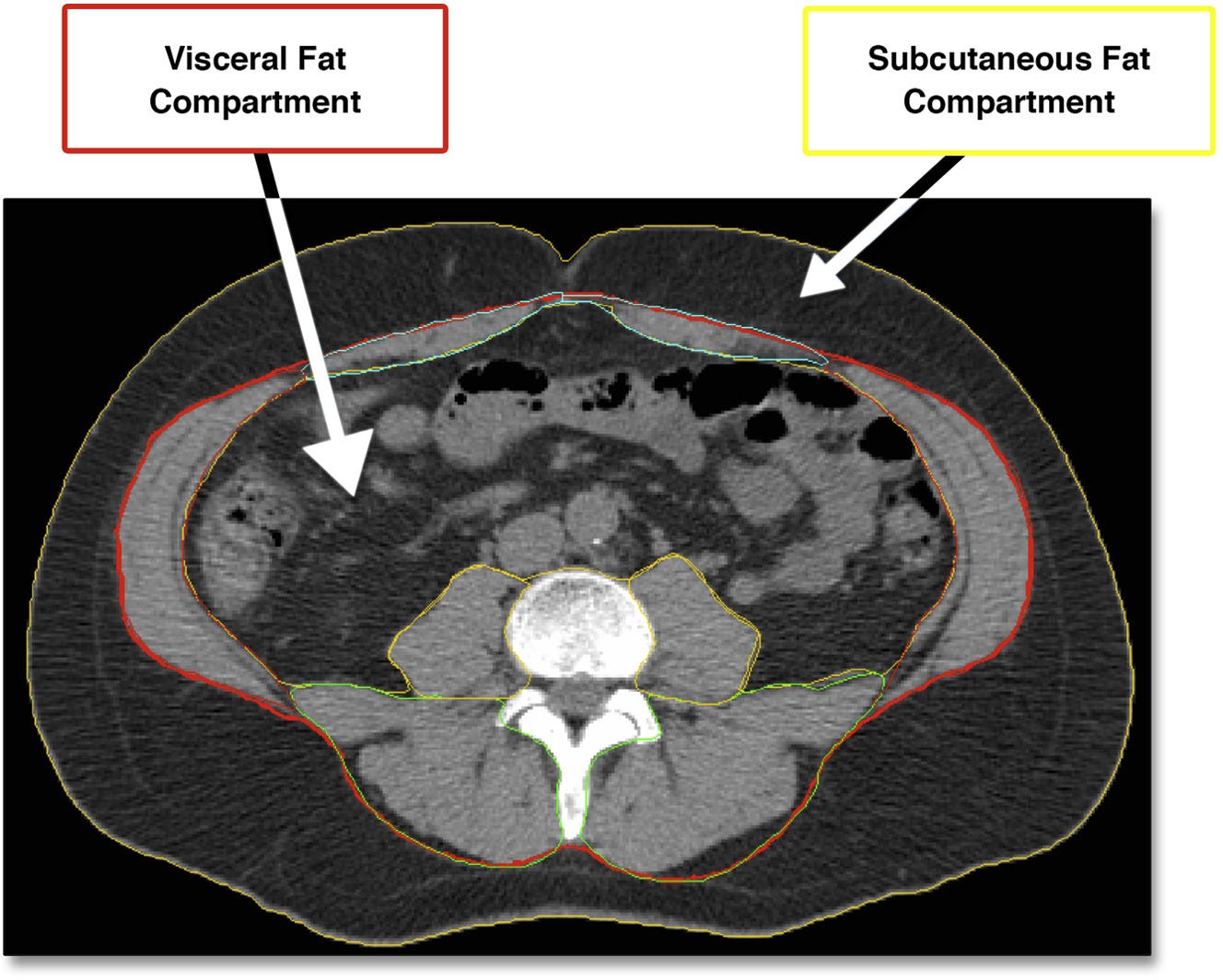

And these brain changes are in turn linked to increased body fat – in particular visceral adiposity, the accumulation of fat within the abdominal cavity. While subcutaneous fat accumulates just under the skin, far from any metabolically important organs, visceral fat is stored around vital internal organs including the liver and pancreas:

Visceral fat releases biochemicals which set off a chain of inflammation throughout the body, including the brain. The neuroinflammatory damage initiated by excess deep belly fat is believed to cause the brain pathologies described above, that result in diminished fluid intelligence.

And that visceral fat-induced inflammatory brain damage begins many years before the first signs of dementia manifest. In a pair of studies led by Mahsa Dolatshahi, MD, MPH, post-doctoral research associate at Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology (MIR) at Washington University School of Medicine, cognitively normal adults with an average age of around 50, underwent bloodwork, abdominal and thigh MRIs, and PET scans to assess the burden of amyloid and tau – two proteins that are believed to interfere with the communication between brain cells, and whose accumulation is a hallmark of certain types of dementia.

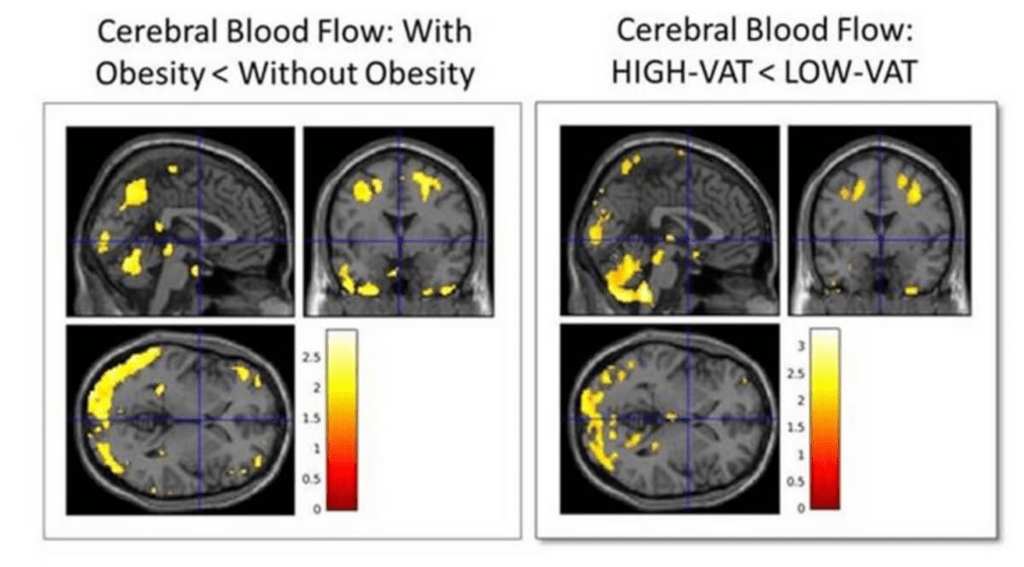

Obesity, especially increased visceral fat accumulation, was associated with decreased blood flow to the brain, especially the middle temporal cortex which is particularly affected in Alzheimer’s disease.1

And people with higher levels of visceral fat had greater accumulation of amyloid and tau in their brains. Furthermore, insulin resistance (which is driven by visceral fat accumulation) was also associated with higher amyloid burden.

The disturbing conclusion is that excessive visceral fat accumulation in midlife is silently, sneakily destroying the brain via multiple mechanisms, setting people up for Alzheimer’s disease in later life:

“Our results may indicate early neurodegenerative processes in AD-related cortical regions transpiring in the midlife population with higher visceral adiposity and insulin resistance, even without any overt cognitive impairment. While our study does not directly reveal specific underlying mechanisms of our observations, visceral adiposity may contribute to the progression of neurodegeneration through increased insulin resistance. Postulated mechanisms include lowering levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is involved in neurodegeneration through altered neural plasticity [46]. Another suggested possible pathway is increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress, and advanced glycation end-products accumulation, increased apoptosis of neuronal cells, and cerebral microvascular disease, starting as early as midlife [47, 48].”

Alzheimer Disease Pathology and Neurodegeneration in Midlife Obesity: A Pilot Study

More brawn, healthier brain

Deteriorating brain function is also linked to a decline in muscle mass and strength. Working muscles release anti-inflammatory substances called myokines, as well as mitigating insulin resistance which is a driver of inflammation.

Researchers utilising data from the UK Biobank, a prospective cohort study which recruited half a million Brits aged 40 to 79 in 2007, have now drawn all of these separate threads of scientific investigation into one cohesive strand, with an important message for anyone who wishes to enjoy their autumn years, with their marbles intact: Develop a healthy body composition (more muscle, less fat) and maintain it as you get older.

In a study titled ‘Aging-related changes in fluid intelligence, muscle and adipose mass, and sex-specific immunologic mediation: A longitudinal UK Biobank study’, the researchers took data from a sub-cohort of 4431 UK Biobank participants who underwent dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scanning to assess their body composition, divided into lean muscle mass, total non-visceral adipose mass (predominantly subcutaneous fat) and visceral adipose mass.

These participants also underwent both blood tests and the Fluid Intelligence Test on three separate occasions.

When all the numbers were crunched, the researchers found that:

Participants with higher lean muscle mass showed gains in performance on the Fluid Intelligence Test over time. This brain-protective effect of muscle mass was stronger in women than men (possibly because on average, men have significantly more muscle mass than women at all stages of life).

Participants with higher fat mass – both visceral and non-visceral (subcutaneous) – showed declines in fluid intelligence scores over time.

Higher body mass was associated with raised levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), a marker of systemic inflammation, although there was no association between CRP and fluid intelligence.

The researchers’ conclusions are well worth noting:

“Aging itself may not be deleterious, but rather age-related changes in body morphometry [lean vs fat mass] that are related to cognitive decline.”

While muscle mass is typically assessed via DEXA scanning, which involves exposure to ionising radiation, existing brain MRIs can be opportunistically used to identify loss of muscle mass in the temporalis (the large and powerful muscle that is used for moving the lower jaw), which is an excellent proxy for muscle loss throughout the body. If you’ve already had a brain MRI to assess a neurological condition (e.g. after suffering a concussion, or for investigation of chronic headaches), you could ask a radiologist to re-examine the scan to assess the size of your temporalis muscles.

According to the co-author of a study designed to ascertain the value of measuring temporalis size in predicting the onset of dementia,

“We found that older adults with smaller [temporalis] muscles are about 60% more likely to develop dementia when adjusted for other known risk factors.”

Muscling your way into better brain function

I have been banging the drum for muscle-strengthening exercise, particularly in older women, for decades (see my previous articles Crossword puzzles or pumping iron – what’s best for maintaining your marbles?, Preventing dementia: Part 2, Muscle up to beat hot flushes, and Exercise is the best medicine for preventing falls and broken bones).

When I ask my older clients about their current exercise habits, those who are physically active almost always nominate walking as their major form of physical activity. Walking is a delightful activity that has much to recommend it (it gets you outdoors in the sunshine, breathing [hopefully] fresh air, and potentially meeting other people), but it is in no way sufficient to maintain muscle mass – not to mention bone mass – as we get older, unless you’re substantially increasing impact by wearing a weighted vest or heavy backpack.

Both men and women need to incorporate regular strength training into their weekly exercise routines. Examples of strength training include:

Weight training, either with free weights (dumbbells, barbells, kettlebells, sandbags) or weights machines at the gym.

Resistance bands and tubes (like these).

Bodyweight exercises such as squats, lunges, push-ups, sit-ups and chin-ups.

Pilates using the Reformer exercise machine.

Aquarobics, especially using foam dumbbells.

Riding an exercise bike or using an elliptical trainer or rowing machine with the resistance cranked up. (Helpful hint: if you can read a magazine or scroll through your Instagram feed while exercising, you’re not working hard enough.)

Battle ropes.

Walking whilst wearing a weighted vest or heavy backpack.

If you’re new to strength training, there are plenty of YouTube fitness channels and free workout videos to get you started. My personal favourite is Fitness Blender which allows you to customise your workout based on available time, fitness equipment, type of workout and difficulty level.

If you are rehabilitating an injury, or have never done strength training before and are feeling overwhelmed, I highly recommend seeing an exercise physiologist who can design a suitable program for you.

The bottom line: Research on the link between body composition and cognitive function underscores the truth of the old adage, ‘ Use it or lose it’. Human bodies were made to move – to walk, run, climb, lift, carry, dig, dance, drag (not to mention making love!) – and when we stop moving, it’s not just our bodies that decline.

The age-old contest between brawn and brains turns out to not be a contest at all. More muscle power equals more brain power, and the connection between the two becomes more important, the older we get.

For information on my private practice, please visit Empower Total Health. I am a Certified Lifestyle Medicine Practitioner, with an ND, GDCouns, BHSc(Hons) and Fellowship of the Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine.

You might remember my previous post, Fat body, starved brain, which discussed a study that found a linear association between body mass index (BMI) and diminished blood flow to the brain, such that those with the highest BMI had the most impaired cerebral blood flow. But an individual could have a higher BMI either because they have a very muscular physique (e.g. body builders and power lifters) or because they're overfat. And they could be overfat either from excessive subcutaneous fat deposition, or excessive visceral fat accumulation. So the study discussed in this post helps to pin down exactly what type of tissue is most dangerous to the brain, when we have too much of it.

so basically, try to get yourself a sixpack?

Due to my job as a geologist, I travel around to remote areas a lot. I have found a combo of body weight exercises to be very convenient, as they can be done anywhere, anytime, everyday, without any equipment.

I wonder if body-builders are the sharpest tools in the shed?