Do childhood vaccines save lives, or cost them?

Do vaccines increase or decrease the number of children who die in the first year of life? Two researchers set out to answer this question. You'll never guess what happened next.

Back in April 2022, I wrote two articles about the impact that the COVID-19 ‘vaccine’ debacle has had on the confidence of the general public and the medical profession in vaccines in general. In the first of those articles, Why you need to stop saying “I’m not an antivaxxer, but…”, I mentioned the 8.93 per cent decline in Florida’s infant mortality rate that coincided with a marked drop in the percentage of children who were fully compliant with the CDC-recommended childhood vaccination schedule. Specifically, there was a 14.1 percentage point drop in children aged 24 to 35 months in the state who were ‘up to date’ with their shots, from 93.4 per cent in 2020 to 79.3 per cent in 2021, and a 5.8 percentage point drop in 1-2 year olds, from 73 per cent in 2020 to 67.2 per cent in 2021.

Huh. But aren’t vaccines supposed to reduce the number of infant deaths by protecting tiny babies with immature immune systems against dangerous infectious diseases? Well, that’s the theory. As I mentioned in that previous article, according to John and Sonia McKinlay’s exhaustive analysis of US data, medical interventions for infectious diseases (including vaccines, antibiotics and diphtheria toxoid) accounted for a measly 3.5 per cent of the steep reduction in total mortality that occurred between 1900 and 1973 in that country; most of that reduction was due to the dramatic decline in deaths from infectious disease. The vast bulk of the decline in infectious disease mortality was directly attributable to ‘old fashioned’ public health interventions including provision of clean water and uncontaminated food, sanitation, and improved housing standards.

And that brings me to three studies which grapple with the important question, ‘Do childhood vaccines help or hinder the attempt to reduce infant mortality?’ Reading and dissecting these studies is an object lesson in how science should and should not be conducted, and the types of statistical sleights-of-hand that researchers can use to torture the data until it confesses, even to crimes that were never committed.

These studies essentially constitute a debate between two teams of researchers, one calling vaccine orthodoxy into question, and the other staunchly defending it. Let’s step through these, in the order in which they were written:

Study #1: ‘Infant mortality rates regressed against number of vaccine doses routinely given: Is there a biochemical or synergistic toxicity?’

This study, published in the journal Human & Experimental Toxicology in 2011, was coauthored by Neil Miller and Gary Goldman. You might remember Goldman from my previous article, Backlash: How the vaccine pushers turned true believers into vaccine sceptics – Part 2. In 2002, he quit his job as a research analyst when his employer, the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, refused to publish his discovery that their paediatric chickenpox vaccination campaign was associated with a dramatic increase in the incidence of shingles in both children and adults. This agency then collaborated with the CDC in a lengthy harassment campaign to try to prevent Goldman from publishing his findings independently.

Rather than being intimidated into silence, Goldman’s bruising experiences prompted him to become curious about the safety and efficacy of vaccines in general.

In collaboration with Miller, Goldman conducted a linear regression analysis on the relationship between infant mortality rates in 34 highly developed countries, and the number of vaccine doses on the immunisation schedules in those countries.

Infant mortality rate (IMR) is the number of deaths of children under 1 year of age, per 1000 live births.

Linear regression is a statistical technique used for modelling the relationship between two factors, known as variables. In simple terms, it’s the first step that needs to be taken in the process of ascertaining whether a correlation between two variables is due to causation rather than coincidence.

The 34 countries selected for this analysis were the US – which, at 26 vaccine doses for infants aged less than 1 year (as of 2011), has both the most intense vaccination schedule and the highest per capita spend on health care in the world – and the 33 countries that have a lower IMR than the jabbed-to-the-eyeballs leader of the free world.

Importantly, most of the nations included in this study had coverage rates in the 90–99 per cent range for the most commonly recommended vaccines – DTaP, polio, hepatitis B, and Hib (when these vaccines were included in the schedule), minimising the impact of any potential confounding effect of variability in coverage rates. Remember this – its importance will become evident when we discuss Study #2.

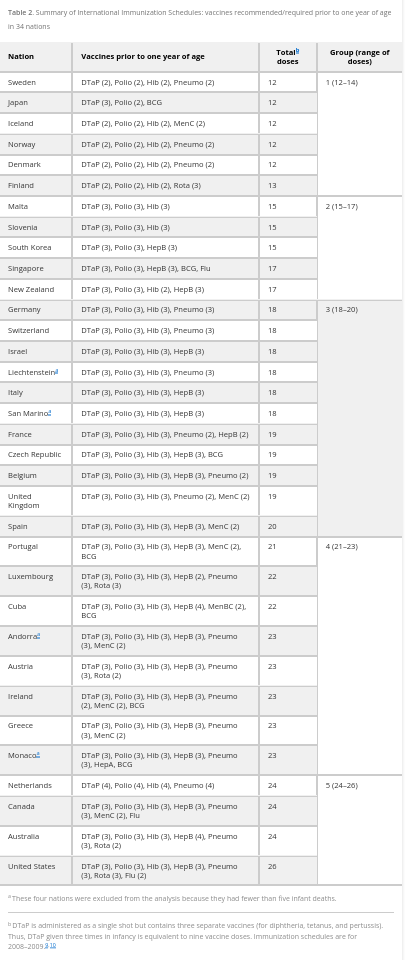

Here are the 34 countries with the lowest infant mortality rates in the world, as of 2009:

(Does it strike you as odd that Cuba has a lower IMR than the wealthy country that has maintained an embargo on it since 1962, crippling its economic development and hindering its access to medical supplies?)

And here are the number of vaccine doses on each nation’s vaccination schedule, as of 2008-2009:

After performing an initial exploratory analysis which indicated that there was indeed a relationship between the number of vaccine doses and IMR, Goldman and Miller then compared average IMRs between groups of nations whose vaccination schedules specified 12-14, 15-17, 18-20, 21-23 and 24-26 doses of vaccines before the age of 12 months. They produced the following chart, which indicates a statistically significant difference in IMRs between countries that give 12–14 vaccine doses and (a) those giving 21–23 doses (61 per cent higher infant mortality rate) and (b) those giving 24–26 doses (83 per cent higher IMR):

(For those unfamiliar with statistics, ‘r‘, or Pearson’s coefficient, represents the strength of association between two variables – in this case, number of vaccine doses and infant mortality rate. The value of r is always between +1 and –1. The closer to +1 r is, the stronger the positive association between the variables. The p value, or probability value, is a statistical measurement used to validate a hypothesis against observed data. The lower the p value (i.e. the smaller the number), the greater the statistical significance of the observed difference; or, in layman’s terms, the less likely it is that the result is due to simple random chance rather than a true association.)

In the discussion section of their paper, Goldman and Miller point out that many developing nations have extremely high vaccine coverage rates yet their IMRs continue to be appalling, and emphasise that no amount of vaccines will compensate for the absence of foundational public health measures:

“For example, Gambia requires its infants to receive 22 vaccine doses during infancy and has a 91%–97% national vaccine coverage rate, yet its IMR [infant mortality rate] is 68.8. Mongolia requires 22 vaccine doses during infancy, has a 95%–98% coverage rate, and an IMR of 39.9.8,9 These examples appear to confirm that IMRs will remain high in nations that cannot provide clean water, proper nutrition, improved sanitation, and better access to health care. As developing nations improve in all of these areas a critical threshold will eventually be reached where further reductions of the infant mortality rate will be difficult to achieve because most of the susceptible infants that could have been saved from these causes would have been saved. Further reductions of the IMR must then be achieved in areas outside of these domains. As developing nations ascend to higher socio-economic living standards, a closer inspection of all factors contributing to infant deaths must be made.”

They go on to discuss the introduction of ‘sudden infant death syndrome’ to medical nomenclature in 1969, after national immunisation campaigns were initiated in the US in the 1960s, and its rapid rise to become the leading cause of postneonatal mortality by 1980. They speculate that overvaccination may impose a toxic burden on infants’ health, and call for rich nations with high vaccine doses and relatively high IMRs to “take a closer look at their infant death tables to determine if some fatalities are possibly related to vaccines though reclassified as other causes”.

The response to this study by academics and policy-makers was deafening silence, until late in September 2021, when a professor from Brigham Young University, Elizabeth Bailey, and several of her students, produced an as-yet-unpublished paper which accused Goldman and Miller of “inappropriate data exclusion and other statistical flaws”. Which brings us to…

Study #2: ‘Infant Vaccination Does Not Predict Increased Infant Mortality Rate: Correcting Past Misinformation’

This paper was first uploaded to the pre-print server medRxiv in September 2021. It has since undergone three revisions without yet being accepted for publication in any peer-reviewed journal.

It is a sign of the extraordinary times that we live in, that in the very title of their paper, the authors denigrate Goldman and Miller’s peer-reviewed, published study as “misinformation”. This is not how scientists behave when they wish to challenge each others’ views.

But as we shall see, this is not primarily a scientific paper, but a propaganda piece that explicitly aims to reduce the general ‘vaccine hesitancy’ that “has intensified due to the rapid development and distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine” – by which I presume they mean that the public has finally twigged to the fact that the inadequately-tested, rushed-to-market COVID-19 ‘vaccines’ are neither safe nor effective, and are wondering whether their asleep-at-the-wheel regulatory agencies have been similarly lax with all the other vaccines that are pumped into them, and their children. (Hint: they have been.)

The authors begin their paper with the stock trope that vaccines are “viewed as one of the greatest public health successes of all time”. As examples of that success, they cite smallpox, poliomyelitis, measles, rubella, tetanus, diphtheria, Haemophilus influenzae type b and unspecified “others”. Yet the McKinlay paper cited above concluded that medical measures made little to no impact on deaths from measles, diphtheria, smallpox and poliomyelitis in the twentieth century; the CDC acknowledges that tetanus mortality had already markedly decreased before routine vaccination began; rubella mortality was already negligible before a vaccine was developed (although this usually benign disease can wreak havoc on the developing foetus when contracted during pregnancy); and implementation of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccination has resulted in an increase in infections caused by non-vaccine preventable strains, and antibiotic-resistant strains of the bacteria.

The authors then go on to claim that “addressing vaccine hesitancy by increasing public confidence in vaccine safety has the potential to positively impact public health and save lives”. To reiterate my earlier point, the contention that vaccines have, do, or will “save lives” is called into question by the McKinlay paper. Furthermore, the net public health impact of vaccination has never been assessed, as this would require a comparative longitudinal study of the overall health of vaccinated vs unvaccinated groups within the same population, and the CDC admits that it has not conducted such a study, nor does it hold any record of such a study.

Finally, the authors get down to the real purpose of the paper: discrediting Goldman and Miller’s study. They seem to be particularly bothered that “this manuscript is in the top 5% of all research outputs since its publication, being shared extensively on social media with tens of thousands of likes and re-shares” (perhaps especially since they can’t even manage to get their own paper published in a peer-reviewed journal after nearly a year and a half, let alone shared widely).

Their chief criticism is that Goldman and Miller cherry-picked data, selecting only 34 countries out of a dataset that included 185 countries. In addition, they accused Goldman and Miller of relying on vaccine schedules rather than data on actual vaccine doses administered.

They conclude that the chief determinant of IMR is actually the Human Development Index, and that, in complete contradiction to Goldman and Miller’s conclusions, “fewer vaccine doses in the schedule were predictive of higher infant mortality rate.”

How did Goldman and Miller respond to this critique of their paper? Let’s turn to…

Study #3: ‘Reaffirming a Positive Correlation Between Number of Vaccine Doses and Infant Mortality Rates: A Response to Critics’

Published in the peer-reviewed journal Cureus on 2 February 2023, this paper examines the claims made in Study #2, and reanalyses the data from the original study published in 2011.

As always, I urge you to read the paper (and the other two referenced above) for yourself, but here’s my quick-and-dirty summary:

Indiscriminately combining developing and developed nations with varying rates of vaccination and vast socioeconomic disparities, as the critics did for their reanalysis, introduces multiple confounding variables that were not present in the original analysis, which was confined to economically developed countries. It is not appropriate to group together for analysis countries as socioeconomically disparate as Belgium (IMR = 4.44) and Angola (IMR = 180.21), just because they both specify 22 vaccine doses in the first year of life. Likewise, it is not appropriate to group Chad, which has a coverage rate of 10 per cent for three doses of the hepatitis B vaccine, with economically developed countries that have greater than 90 per cent coverage, and not adjust for confounding.

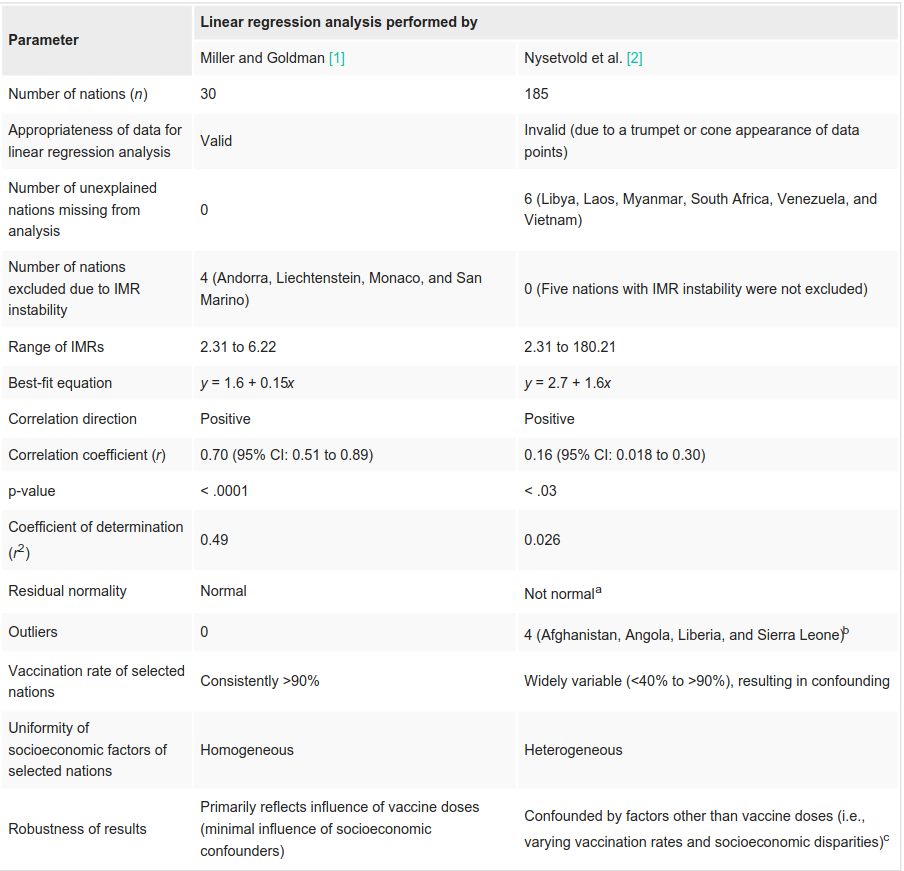

Despite these confounding variables, there was still a small but statistically significant correlation between total vaccine doses and IMRs in the reanalysis (r = 0.16 for the dataset of 185 countries, compared to r = 0.7 for the 30 countries with the lowest IMRs).

The critics’ claim that the Human Development Index (HDI) – rather than number of vaccination doses – predicts IMR, is not justified, because of a number of well-known errors of misclassification in the HDI.

There are significant flaws in the critics’ linear regression analysis of IMR as a function of percentage vaccination rates, which essentially invalidate their findings.

The critics failed to count doses of vaccines accurately for several countries, because they relied on UNICEF data rather than cross-checking with each country’s published vaccination schedule. In the case of Indonesia, this resulted in the critics counting just seven vaccine doses, while the true number of doses administered is 18. They also reported only seven infant vaccine doses for Australia when the true value is 24.

The critics excluded six countries from their analysis without explanation, and included five countries that should have been excluded because they have so few births, that their IMR is unstable.

Goldman and Miller invited an independent statistician to conduct an odds ratio analysis on the original dataset, controlling for 11 different variables (including low birth weight, child poverty, and breast feeding), which confirmed their original findings of a strong correlation between vaccine doses and IMR.

There were still statistically significant correlations between number of vaccine doses and IMR when they expanded their original analysis from the top 30 to the 46 nations with the best IMRs. After this point, there is too much heterogeneity between the socioeconomic conditions of nations for a consistent relationship between vaccine doses and IMR to be apparent.

Replicating their original 2011 study using updated 2019 data corroborated the trend they found in the first paper, namely that the more vaccine doses, the higher the IMR.

Goldman and Miller summarised their response to the critics in the following table:

It gets even worse. In the supplementary material for the paper, Goldman and Miller reveal that in earlier versions of their critics’ paper, the authors made several libellous statements that were so egregious that

“an attorney contacted a faculty chairman to inform the Bailey team that their article sets a poor example to students that libel is acceptable, and suggested that they remove their malicious and false statements prior to going forward with publication. Although this language was adjusted in later versions, it served to reveal author bias and demonstrated a misunderstanding and misuse of basic scientific methodologies.”

The original version of the paper also made false claims about the funding source for Goldman and Miller’s paper, and, despite claiming that they used an “identical dataset” for IMRs as that which was used in Study #1, they in fact used a different dataset retrieved from an alternate resource containing less recent IMR data; as one example, “the IMR for Sierra Leone in the CIA dataset that we used is 81.86 but the Bailey team has it listed as 154.43 and used this figure in their analyses.”

But yeah, apart from all that, it was quality work.

Goldman and Miller go on to discuss the biological plausibility of an association between infant vaccination and sudden infant death, citing:

The abrupt disappearance of the category ‘sudden [infant] death’ in Japan when Japanese authorities raised the age of pertussis (whooping cough) vaccination from three months to two years;

A 1987 study which found that infants died at a rate more than seven times greater than expected in the period zero to three days following DTP vaccination when compared to the period beginning 30 days post-vaccination;

A 2021 analysis by Miller of Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) data which found that 58 per cent of the 2605 infant deaths reported to VAERS from 1990 to 2019 occurred within three days post-vaccination, and 78 per cent occurred within seven days post-vaccination;

Compensation has been paid to parents of children who died after receiving vaccines, with acknowledgement that vaccines drive the production of cytokines which can interfere with the brain’s ability to regulate breathing, resulting in the abrupt cessation of breathing that characterises sudden infant death syndrome.

They concluded that

“A positive correlation between the number of vaccine doses and IMRs is detectable in the most highly developed nations but attenuated in the background noise of nations with heterogeneous socioeconomic variables that contribute to high rates of infant mortality, such as malnutrition, poverty, and substandard health care.”

Why does this matter?

The significance of this tale of three papers goes way beyond a somewhat entertaining spat between two teams of data nerds. (“Cop this regression analysis straight in your goolies! Right back at you with a devastating odds ratio analysis to your solar plexus!”)

The salient difference between Goldman and Miller, and Elizabeth Bailey and her coauthors, is that the former are independent researchers while the latter are attached to an educational institution. As evolutionary biologists Heather Heying and Bret Weinstein frequently point out in their Dark Horse podcast, universities have been entirely captured by an entity that might be described as the medical-academic-pharmaceutical-industrial complex. Their apparatchiks, like Elizabeth Bailey, perform something that has the cosmetic appearance of science but is definitively not science, in the sense of conforming to the scientific method and the attitude of radical scepticism that underpins it.

If you recall Gary Goldman’s story, which I recounted in Backlash: How the vaccine pushers turned true believers into vaccine sceptics – Part 2, he took a job as a research analyst with the LA County Health Department having never questioned the safety or effectiveness of vaccines. However, when the data that he was analysing indicated that chickenpox vaccination was leading to significant harm in the form of increased incidence of shingles, Goldman followed those data where they led, even though this meant revising his entire belief system (not to mention losing his job and suffering significant harassment by his former employer).

The lesson of the last three years of COVIDiocy has been that only a tiny minority of scientists display this level of integrity and commitment to uncovering the truth and disseminating it to the public. And when they do so, they are vehemently opposed by the majority, who have, through some strange quirk of human psychology, assumed the interests of the medical-academic-pharmaceutical-industrial complex as their own.

Substacker El Gato Malo (the Bad Cat) frequently writes of the politicisation of science and the need to open data to public scrutiny and crowd-source its analysis through a genuine peer review system. This is the way of the future. Open the books. Free the data. Question everything.

Great stuff!

As a nerd spectator, I love it when "my" nerd team lands an odds ratio blow to the goolies. That's basically what the entire "Turtles all the way down" book is about.

IMO, the knockout blow is not in the deaths, but in the injuries. It is hard for most people to care about dead babies, especially if their own kids survived the jab Russian Roulette. Yet somehow they can manage to care about test scores and behavioural problems. (https://childrenshealthdefense.org/wp-content/uploads/Vaxxed-Unvaxxed-Parts-I-XII.pdf)

If vaccines were good there would be no need for mandates, propaganda, censorship of dissenting views and legal immunity to manufacturers.