5 reasons to think twice before taking blood pressure drugs

High blood pressure kills. But many of the drugs prescribed to treat it are doing more harm than good.

High blood pressure, or hypertension, is often dubbed 'the silent killer'.

There’s no disputing its credentials as a killer: Almost 20 per cent of early deaths across the world are linked to elevated blood pressure... and most shockingly, in the study that reached this conclusion, 'elevated' was defined as a systolic blood pressure greater than 115 mm Hg1. (Most people still believe that a blood pressure of 120/80 mm Hg, i.e. a systolic pressure of 120, is healthy and normal.) No other risk factor or condition plays a bigger role in reduced quality of life and premature death, because high blood pressure is "the leading global risk factor for cardiovascular, renal, neurological and ophthalmologic diseases".

And yet, the vast majority of people do not experience any symptoms from hypertension - that's the 'silent' part.

What exactly does elevated blood pressure do to us?

It is the most significant risk factor for stroke and congestive heart failure. People with high blood pressure (that is, systolic blood pressure of 160 mm Hg or higher and/or diastolic blood pressure 95 mm Hg or higher) have four times the risk of stroke compared to people with normal blood pressure.

It accelerates the development of atherosclerosis, the build-up of lipid-laden plaques on the inner lining of the artery walls, and it increases the likelihood that one of these plaques will rupture, triggering a heart attack or embolic (clotting) stroke.

It damages the delicate filtration mechanism in the kidneys. Even worse, since the kidneys play a key role in regulating blood pressure, this damage engenders a vicious circle of escalating blood pressure and organ destruction, which may eventually result in kidney failure and the need for dialysis.

It damages the fragile blood vessels that supply the eyes with blood, causing hypertensive eye disease. Chronic high blood pressure can cause these blood vessels to rupture, resulting in blurred vision and even blindness.

And it accelerates dementia; having high blood pressure in midlife is a particularly strong risk factor for developing dementia in later life.

Given these harms, high blood pressure obviously requires urgent treatment. But are prescription drugs the answer?

All classes of antihypertensive (blood pressure-lowering) drugs present serious hazards, including these:

#1. Diuretics (commonly used as first-line therapy in hypertension) increase the risk of developing diabetes and arrhythmias.

An analysis of 22 clinical trials including 143 153 participants who were free of diabetes at enrolment, found that those who were prescribed a diuretic (such as Moduretic, Chlotride or Lasix) had a significantly higher likelihood of developing diabetes. Having diabetes dramatically increases your risk of both stroke and heart disease - the very conditions that antihypertensive medications are intended to reduce!

(Angiotensin receptor blockers [ARBs], angiotensin converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors and calcium channel blockers are far less likely to precipitate diabetes.)

Diuretics can also cause abnormal heart rhythms (known as arrhythmias) which increase the risk of sudden cardiac death.

#2. Beta-blockers also increase diabetes risk, increase the risk of stroke and death in newly-diagnosed diabetics, and DO NOT lower the risk of either complications or death in simple hypertension, nor in people with heart failure.

The European Society of Hypertension now recommends beta-blockers as first-line agents for hypertension, whilst the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and the National Heart Foundation of Australia do not. Nonetheless, in my clinical practice, I regularly see people who are taking a beta-blocker despite having 'simple' high blood pressure, uncomplicated by any of the conditions that are considered (questionably, as we shall shortly see) to warrant this prescription, such as heart failure or a history of heart attack.

Beta-blockers (such as Inderal, Visken and Betaloc) raise the risk of developing diabetes by around 30 per cent, with the risk rising the longer you stay on them. Since patients are usually told they will have to take antihypertensives for the rest of their lives, this should give serious pause for thought. Furthermore, in patients with new onset diabetes, beta-blockers increase all-cause mortality by 8 per cent and stroke by 30 per cent.

Beta-blockers are commonly prescribed to lower heart rate in patients at high risk of heart attack, but a meta-analysis of over 70 000 such patients found that "beta-blocker–associated reduction in heart rate increased the risk of cardiovascular events and death for hypertensive patients". Those whose heart rate was lowered the most by beta-blockers, had the greatest risk of stroke, heart attack, heart failure and death.

Beta-blockers DO NOT show any advantage over other antihypertensive medications for the prevention of heart failure in people with high blood pressure. And when compared to other classes of antihypertensives, they raise the risk of stroke by 19 per cent in elderly patients while providing no benefit for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality or heart attack.

The authors of a major review on beta-blockers concluded that

"Despite the blood pressure lowering effect, beta-blockers have little, if any, efficacy in reducing stroke and MI [heart attack] in hypertensive patients as was shown in a variety of prospective, randomized trials and meta-analyses."

Cardioprotection with beta-blockers: myths, facts and Pascal’s wager

#3. Calcium channel blockers dramatically increase the risk of dying from cardiovascular disease, especially when combined with diuretics.

The long-running Nurses' Health study identified over 14 000 women who reported hypertension and regular use of antihypertensive drugs (diuretics, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors, or any combination of these) in 1988, and followed them up until 1994. Researchers found that women who were taking calcium channel blockers (such as Norvasc, Adalat and Isoptin) alone, had more than double the risk of heart attack as those prescribed thiazide diuretics. After adjustment for various confounding factors, the relative risk was 1.64. Interestingly, the association between calcium channel blocker use and heart attack was only found in women who had ever smoked cigarettes.

Along similar lines, the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study tracked over 30 000 women with hypertension but no history of cardiovascular disease (CVD), and compared the outcomes of women on a variety of different antihypertensive medications. Women treated with calcium channel blockers alone had a 55 per cent greater chance of dying from CVD than women treated with diuretics alone; while those on a combination of a calcium channel blocker plus a diuretic had a massive 85 per cent greater risk of CVD death compared to those treated with a diuretic plus a beta-blocker. Even worse, when women with diabetes were excluded from the analysis, those taking the calcium channel blocker-diuretic combo had more than twice the risk of dying of cardiovascular disease.

Meta-analyses have reached differing conclusions on the risks and benefits of calcium channel blockers. This one found a significantly higher risk of acute myocardial infarction (heart attack), congestive heart failure, and major cardiovascular events in people taking a calcium channel blocker when compared with patients assigned diuretics, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, or clonidine. This one found an increased risk of heart failure in coronary heart disease patients but not in those with uncomplicated hypertension, and no increased risk of myocardial infarction, cardiovascular death and major cardiovascular events. However, significant heterogeneity between study results was identified. That is, the studies included in this meta-analysis diverged substantially in their findings on a number of outcomes. In the face of these contradictory results, doctors and patients alike are left wondering, 'Is it safe to take these drugs?'

#4. Angiotensin receptor blockers increase the risk of cancer.

Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs, such as Neosartan, Micardis and Pritor) affect hormone receptors involved in several factors relating to cancer growth: regulation of cell proliferation, angiogenesis (the development of a new blood supply, allowing a tumour to grow), and tumour progression. Researchers found an 11 per cent increased risk of cancer in patients who had been on an ARB for at least one year. Lung cancer was the only solid organ cancer with a statistically significantly higher risk in ARB users; the risk was 25 per cent higher.

More recently, a meta-regression analysis of randomised trials, involving a total of just over 74 000 patients, confirmed that taking a daily high dose of an ARB for longer than 3 years increased the risk of all cancers combined by 11 per cent, while taking any dose of an ARB for longer than 2.5 years increased the risk of lung cancer by 21 per cent.

#5. Over-aggressive treatment of high blood pressure by any drug increases the risk of death in people with coronary artery disease (which is virtually everyone over the age of 60 who has eaten the typical western diet).

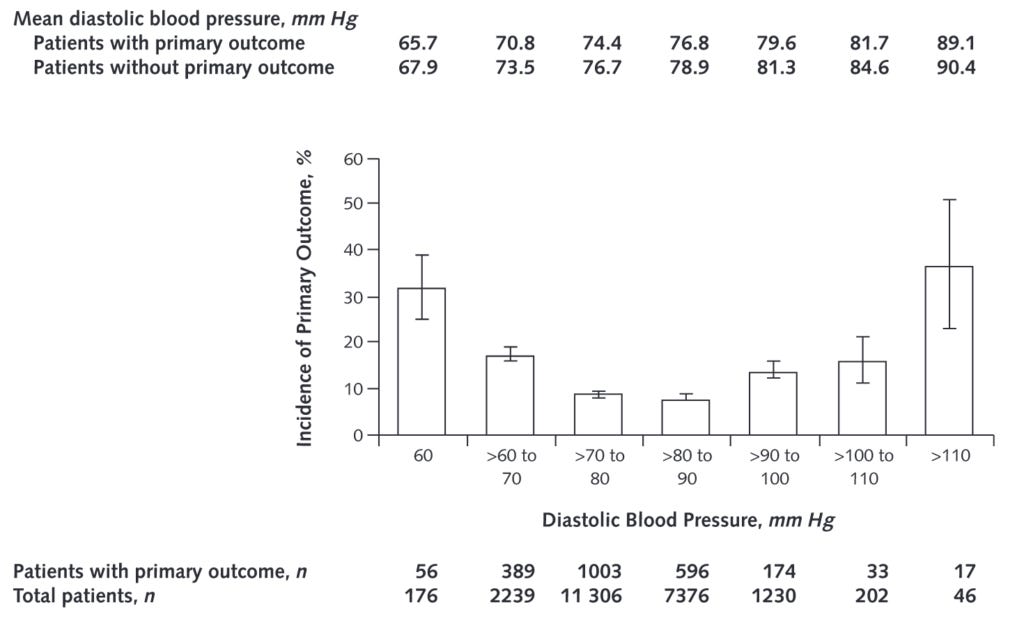

An analysis of 22 576 patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease who were randomly assigned to treatment with either verapamil (a calcium channel blocker) or atenolol (a beta-blocker), found that the patients whose diastolic blood pressure was reduced to 60-70 mm Hg on medication had almost double the risk of death or nonfatal heart attack or stroke, compared to those with a diastolic pressure of 80-90 mm Hg. Those whose diastolic BP was pushed down to 60 mm Hg or less had triple the risk!

Why is aggressive lowering of diastolic pressure so dangerous? The authors propose that it could compromise blood flow to target organs, including the heart itself, which can cause cardiac ischaemia - lack of blood flow from the coronary arteries into the heart muscle.

Between a rock and a high pressure place?

Sharp-eyed readers will have noticed that patients whose diastolic blood pressure remained above 90 mm Hg on treatment had a heightened risk of the primary outcome of this study, which was the first occurrence of all-cause death, nonfatal heart attack, or nonfatal stroke. So if your blood pressure medication regime either lowers your diastolic pressure too much or not enough, you are more likely to die or suffer a heart attack or stroke.

Meanwhile, as you'll recall from the introduction to this article, having a systolic pressure greater than 115 mm Hg puts you at increased risk of premature death, cardiovascular, kidney, neurological and eye diseases. In fact, a meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials of blood pressure-lowering drugs found that the ideal unmedicated blood pressure is 110/70 mm Hg. Patients whose blood pressure was this low without medication experienced no benefit, in terms of reduced risk of coronary heart disease and stroke, from taking antihypertensives.

Drawing all these threads together, it’s healthy to have a blood pressure of 110/70 if you achieve it without medication, but it’s dangerous to drive your blood pressure down to this level with medication… and it’s also dangerous to let it run somewhat higher than that on medication.

Given these extremely worrying and perplexing findings, what is a person with high blood pressure supposed to do?

Take the pressure down!

If you have recently discovered you have high blood pressure but are not yet on medication, I cannot stress strongly enough the importance of adopting a comprehensive blood pressure lowering program, incorporating evidence-based dietary modification, regular exercise, and sleep and stress management. I'll be outlining such a program in next week's post.

Many of my clients have achieved phenomenal results after just a couple of weeks on a comprehensive diet and lifestyle program, lowering their blood pressure to the point where their GP told them they no longer needed medication.

Obviously, if you are already on blood pressure medication, you cannot simply stop taking it abruptly. I advise clients who are taking antihypertensives to buy a home blood pressure monitor when they commence my blood pressure-lowering program. They take their BP regularly, present the results to their GP, and as their blood pressure drops (which it almost invariably does), the GP can taper their antihypertensive medication.

The bottom line: If you have high blood pressure, you need to be on an integrated program that addresses all the factors that cause blood pressure to rise in the first place, and therefore lowers your risk of heart attack, heart failure and stroke - not a drug that simply forces your blood pressure down, while increasing your risk of getting cancer or diabetes, suffering a stroke or heart attack, or dying!

Finally, I put many hours into writing these posts. If you feel you are getting value from reading my work, please consider a paid subscription:

Worried about your blood pressure and other markers of cardiovascular health? Confused about which medications you should be taking... or whether you should be on them at all? Apply for a Roadmap to Optimal Health Consultation and let's get the pressure down... for good!

mm Hg stands for millimeters of mercury, which is the standard way of measuring blood pressure

Exactly what I needed this week. My dental patients are now asking me about what medications they should be taking because they are questioning the MDs who always push another pill. Not knowing much about the anti-hypertensives, this was a phenomenally times post and will help me to help others. Thank you!!

Yup, I have spoken with Goldhamer and with one of their staff doctors, and I can already see that it's drifting lower with my monthly 3-day fasts, so I am pretty optimistic that with a longer fast, I might establish a lower plateau.