H.G. Wells opened his 1898 science fiction classic The War of the Worlds with these immortal lines:

“No one would have believed in the last years of the nineteenth century that this world was being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater than man’s and yet as mortal as his own; that as men busied themselves about their various concerns they were scrutinised and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinise the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. With infinite complacency men went to and fro over this globe about their little affairs, serene in their assurance of their empire over matter. It is possible that the infusoria under the microscope do the same.”

H.G. Wells, The War of the Worlds

Wells made bacteria – first observed by the Dutch self-taught scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek under his home-made microscope in 1683 – the unlikely heroes of his futuristic novel.

From the moment the vastly technologically superior Martians landed on Earth to commence their invasion, they were colonised by bacteria to which humans, through “natural selection of our kind… [had] developed resisting power.”

The Martians, having eradicated bacteria from their own planet in the distant past, lacked this resistance, and hence “our microscopic allies began to work their overthrow”.

Where human technology proved impotent, “the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water” succeeded in bringing about the destruction of the invading Martians in a matter of weeks.

Little did Wells know just how prescient his description of bacteria as “our microscopic allies” would turn out to be.

For a century, researchers slowly but steadily gathered knowledge of the bacteria that inhabit the human gut, their progress hindered by having to rely on culturing bacteria recovered from stool in a petri dish.

Gut microbiota research as we now know it only really got underway in the late 1990s, with the development of technology that allowed scientists to sequence the DNA of our gut bacteria.

At this point it was discovered that the vast majority of the teeming hordes of tiny critters that inhabit our insides can’t be cultured at all, as they die when exposed to air.

And no one – not even Wells, had he lived long enough – would have believed in the last years of the twentieth century, just how great an influence these microscopic life forms would be discovered to exert on every aspect of human health and well-being.

The field of gut microbiota research has mushroomed so dramatically, that a scientific paper published in 2018 calculated that over four-fifths of the total number of scientific publications focusing on the gut microbiota over the previous 40 years were published in just four years – 2013-2017.

And now in 2023, so many scientific articles on the topic are published every day that it’s impossible to keep up with them all.

In just a few decades, researchers have come to understand that the communities of bacteria, archaea, protists, fungi and viruses that live inside our gastrointestinal tract (our gut microbiota), and their collective genetic material (our gut microbiome) are so vital to healthy function that they constitute a distinct organ of the human body.

Here are just some of the roles played by the 100 trillion microorganisms that populate our gut:

Immune functions: Formation of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue, or GALT (a key component of the immune system in the gut) and ‘training’ of our immune cells to distinguish self from non-self, and friend from foe.

Gut functions: Maintaining the intestinal barrier (i.e. preventing and repairing leaky gut); digesting complex carbohydrates found in human breast milk and in plants; producing short chain fatty acids which feed the cells that line our colon; keeping disease-causing bacteria, yeasts and fungi at bay; regulating muscle movement in the intestinal tract (motility); and protecting against colon cancer.

Metabolic functions: Regulating serum cholesterol, blood glucose levels and appetite - including stimulating release of the appetite-suppressing hormone, GLP-1, that is the target of the latest iteration of blockbuster weight loss drugs such as Wegovy, Ozempic and Saxendra (but without the nasty side effects such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, constipation, pancreatitis, kidney injury, gallbladder disease, thyroid cancer and suicidal thoughts).

Vitamin production: Producing vitamins B1, B2, B12 and K, along with biotin, folate and alpha-lipoic acid.

Central nervous system functions: Stimulating development of parts of the brain, especially the hippocampus (which plays key roles in motivation, emotion, learning, and memory); and producing chemicals that affect areas of the brain involved in appetite control and food cravings.

Enteric nervous system (‘gut brain’) functions: Producing neurotransmitters – chemicals that nerve cells use to talk to each other, and to muscles and glands – including GABA, serotonin and dopamine, and influencing the neuroendocrine cells in the gut that also release these neurotransmitters.

Remarkably, although about one third of the bacterial species that inhabit our guts are common to most people, the remaining two thirds are unique to each individual – as unique as their fingerprint. Although we are about 99.9% identical to each other in terms of our human genome, our gut microbiomes can differ by up to 90%.

Our core microbiota is inherited from our mother, and remains more similar to hers than to unrelated people’s for our entire lifespan.

However, our diet, exercise, lifestyle habits and medication use shape our complex microbial communities and their gene expression throughout life, so that even identical twins, who share the exact same human genome, end up with distinct microbial profiles – although more similar to each other’s than either non-identical twins, or non-twin siblings.

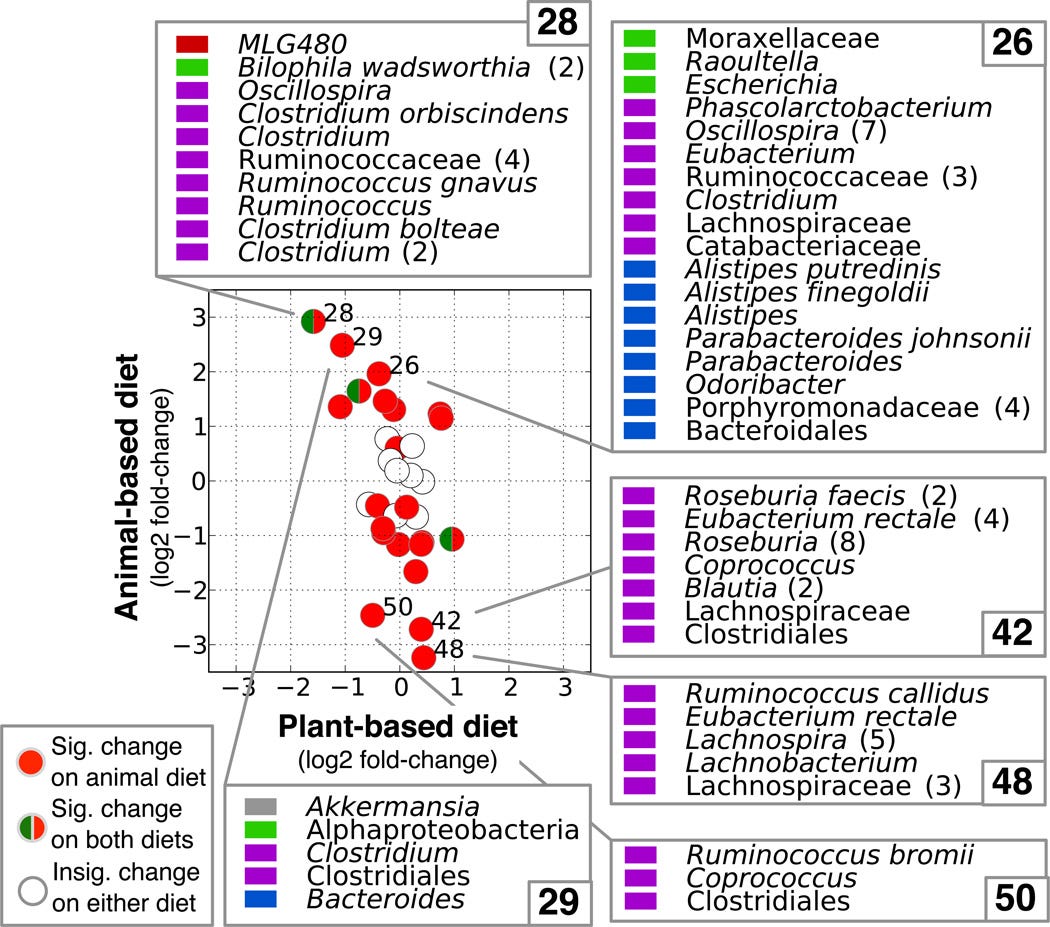

What we eat, in particular, powerfully and rapidly influences the composition of our gut bacteria, and their gene expression. In a landmark study published in 2014, researchers fed 10 volunteers on two different diets – a ‘plant-based diet’ rich in grains, legumes, fruits, and vegetables; and an ‘animal-based diet’ comprising meats, eggs, and cheeses – for 5 days each.

The animal-based diet increased the abundance of bile-tolerant microorganisms (Alistipes, Bilophila and Bacteroides) and decreased the levels of species that metabolise dietary plant polysaccharides (Roseburia, Eubacterium rectale and Ruminococcus bromii) – in just two days!

Furthermore, on the animal-based diet, bacteria expressed more genes involved in synthesising a bile acid that is known to promote liver cancer, and hydrogen sulphide, a gas linked to inflammatory bowel disease and bowel cancer.

Fortunately for the participants, their gut microbiota reverted to their original structure two days after the all-animal food diet ended and they resumed their normal eating pattern. But just imagine the damage they would do if they ate such a diet over the long term!

Actually, you don’t have to imagine. Extensive studies have found that people who habitually eat a Western-style diet – high in meat, fat and refined carbohydrate, and low in fibre and other forms of complex carbohydrate found in whole plant foods – have been found to have a microbiota profile dominated by Bacteroides species. This is associated with increased inflammation, weight gain and impaired blood sugar control.

High fat diets have been found to suppress beneficial bacteria including Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Akkermansia muciniphila, all of which help to maintain a healthy gut barrier; and fuel the growth of Oscillibacter and Desulfovibrio species, which increase intestinal permeability and hence, inflammation.

Saturated fat – found primarily in animal products including meat, poultry, dairy products, eggs and some species of oily fish, as well as coconut oil and palm oil – is the biggest culprit in enriching the gut microflora with bacteria that contain lipopolysaccharide (LPS), also known as endotoxin. LPS is a bacterial component that damages the gut barrier and drives up systemic inflammation levels.

Hence, the typical Western diet creates the perfect storm for generating both dysbiosis (an unhealthy change in microbial composition) and increased gut permeability (‘leaky gut’). Together, dysbiosis and leaky gut play pivotal roles in a host of human maladies including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), coeliac disease, diabetes, asthma, depression, anxiety, and autism.

On the other hand, diets rich in fibre and unrefined carbohydrates have been linked to a Prevotella-predominant microbiota profile.

This cluster of bacterial species ferments the types of carbohydrates that humans are unable to digest – fibre, resistant starch and oligosaccharides, collectively known as microbiota-accessible carbohydrates, or MACs – into beneficial short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including butyrate, acetate and propionate.

These SCFAs bestow a bounty of health benefits, including reducing inflammation both in the gut itself and throughout the entire body, strengthening and repairing the gut barrier, tamping down cholesterol synthesis, improving insulin sensitivity (and thus reducing blood glucose levels), promoting immunity, regulating our appetite, increasing fat-burning, and stimulating the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), the so-called ‘Miracle-Gro for the brain’.

Unsurprisingly, people who eat plant-centric diets have been shown to have greater gut microbial diversity and richness of species, which is associated with better digestive health and lower risk of obesity and metabolic disease (such as diabetes).

Researchers describe the link between diet, gut bugs and obesity with a colourful analogy:

“The obese gut microbiota is not like a rainforest or reef, which are adapted to high energy flux and are highly diverse, but rather may be more like a fertilizer runoff where a reduced diversity microbial community blooms with abnormal energy input.”

But ultraprocessed vegan junk food, stripped of its fibre and complex carbohydrates and laced with fat, sugar and simple starches, just doesn’t cut the microbial mustard. To cultivate your garden of healthy gut bugs, you must feed them a variety of whole and minimally-processed plant foods, rich in microbiota-accessible carbohydrates – big MACs such as legumes (dried lentils, peas and beans), whole grains, vegetables, fruits and nuts, not Big Macs (even vegan ones!).

Why does variety matter? The American Gut Project – a crowdsourced, global citizen science effort which has sequenced the gut bacteria of more humans than any organisation on Earth – found that people who ate 30 or more different plant foods per week had the most diverse gut microbiota.

‘Eating the rainbow’ ensures that your gut bugs have access to a plethora of polyphenols, plant compounds which boost the growth of beneficial bacteria, such as:

Resveratrol (found in grapes, peanuts, pistachios, blueberries, cranberries, and cocoa);

Curcumin (turmeric);

Lignans (flax and sesame seeds);

Quercetin (onions, apples, grapes, berries, broccoli, citrus fruits, cherries, tea, and capers);

EGCG (green and white tea); and

Isoflavones (soy).

Plants produce polyphenols to defend themselves against stress caused by poor soil, fungal disease and insect predation. These powerful plant compounds pass through our upper gut largely intact, but once they reach our colons, gut bacteria begin to metabolise them into active compounds that we can absorb through the colon wall. These compounds deliver a stunning array of health benefits including antioxidant, anticancer and antimicrobial activity, and hormone modulation.

As far as we know, we are not “being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater than man’s”, as H.G. Wells imaginatively speculated in the opening lines of The War of the Worlds.

It’s not Wells’ hostile Martians that we have to fear, after all. It’s ourselves. Our “infinite complacency” has caused up to disrupt the harmonious relationship between our human and microbial selves – a relationship which supported the health, growth and development of our species over the long march of evolutionary time, allowing humans to adapt to seasonal and geographic changes in food supply.

However, in the last few decades, we have relentlessly carpet-bombed our gut microbiota with antibiotics; disrupted their normal transmission from mother to infant with caesarean sections and formula feeding; and starved the most beneficial species of the MACs they need, while overfeeding the most disease-causing ones on excess calories, fat and protein.

In their article ‘The ancestral and industrialized gut microbiota and implications for human health’, pioneering gut microbiota researchers Drs Justin and Erica Sonnenburg argue that due to the damage we have inflicted on them, for the first time in our millennia-long partnership our gut microbiota are no longer acting in our best interests:

“The microbiota associated with humans in the industrialized world has diverged in its compatibility with the less malleable human genome.”

The ancestral and industrialized gut microbiota and implications for human health

The “infusoria under the microscope” adapt in order to survive and thrive. It is up to us to provide them with an environment in which those that thrive, also support our own thriving. And the best way to do that, is with a diet centred on a rich abundance of whole and minimally processed plant foods.

Great reading Robyn, you're a great human being.👍🇦🇺

Righteous anger aka venting.👍🇦🇺💪