This is the final instalment of my three part series examining the corrosive effects of the politicisation of science. If you haven’t already done so, please Part 1 and Part 2 now because I’m going to dive straight back into this topic with…

Exhibit 3

In many ways, the article that I’m going to dig into in this post, titled ‘The narrative truth about scientific misinformation’, is a natural successor to the papers that I’ve examined in the previous two instalments. It argues, in essence, that since people’s beliefs and behaviour are more influenced by stories than by facts, those who wish to persuade the public to believe or do whatever “science” tells - or, more accurately, those who wield it to maintain their authority - them to should turn to “narrative” – story-telling – to achieve their aims, rather than seeking to teach their audience to understand the facts that the scientific method has established, to connect those facts in a systematic and logical fashion, and to make rational decisions on the basis of those facts.

The article, by journalism professor Michael Dahlstrom, is so littered with highly questionable assumptions and internal self-contradictions that it’s hard to know where to even begin when discussing it, but this is its message, in a nutshell:

Ordinary people – that is, non-scientists – are not capable of understanding science.

Hence, ordinary people must rely on experts who do understand science to make important decisions that affect their lives.

Because ordinary people are too stupid and irrational to understand the scientific basis of those decisions, it’s both acceptable and expedient to tell them emotionally-charged stories that persuade them to go along with the decisions that have been made on their behalf by experts.

Let’s dig into three of the major false premises implicit in the article.

False premise #1: There is an institution called “science”, and this institution operates in a completely objective and unbiased fashion to “uncover general truths about the world that are empirically true” and disseminate them, for the betterment of all.

While not explicitly stated, this premise underlies the entire argument laid out in the paper. For example, Dahlstrom states that:

“The societal role of science is tightly coupled with knowledge. Because science creates and refines what is known about the world, a common goal for science communication is to increase scientific knowledge so people can make informed decisions about their lives.”

While it is certainly true that the scientific method is the most powerful tool yet discovered for understanding the world, it is completely inaccurate to describe this as its “societal role”. On the contrary, the societal role of science is to buttress the power of those in authority by legitimising it with a metaphorical scientific seal of approval, as Matthew Crawford pointed out in his excellent essay, ‘How science has been corrupted’, which I quoted extensively in Part 1:

“As a practical matter, ‘politicised science’ is the only kind there is (or rather, the only kind you are likely to hear about). But it is precisely the apolitical image of science, as disinterested arbiter of reality, that makes it such a powerful instrument of politics.”

To understand what Crawford means by “politicised science”, let’s start by clarifying what is meant by politics. Freebase offers the following definition: “The art or science of influencing other people on a civic or individual level”. Wikipedia defines politics as “the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations between individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status”.

Every aspect of science is heavily politicised. For example, the work that scientists do requires funding. Both public and private institutions that fund scientific activity have an agenda which they wish the scientists’ output to serve, and scientists learn very quickly that grant applications that serve such agendas are infinitely more likely to be approved than those that don’t.

Next, in order to be disseminated to the wider world, scientists must publish their results in scientific journals. However, studies whose outcomes are unfavourable to funders’ agendas, or that produce “controversial results and results that contradict existing knowledge” are far less likely to be published at all, and if they are published, are more likely to be accepted by less prestigious journals, resulting in decreased visibility both to other scientists and to the general public.

The peer review process, in which journals send submitted articles to a number of individuals who are considered experts in the relevant field to determine whether they should be published, is dangerously politicised. The ClimateGate scandal, in which leaked emails revealed concerted attempts by a handful of climate scientists to manipulate the peer review process in order to prevent dissenting scientists’ work from being published, and thus produce the impression of a solid scientific consensus on anthropogenic global warming, is a case in point.

Richard Horton, long-time editor of The Lancet, which is currently ranked as the #2 top medical journal in the world, wrote of peer review:

“The mistake, of course, is to have thought that peer review was any more than a crude means of discovering the acceptability – not the validity – of a new finding. Editors and scientists alike insist on the pivotal importance of peer review. We portray peer review to the public as a quasi-sacred process that helps to make science our most objective truth teller. But we know that the system of peer review is biased, unjust, unaccountable, incomplete, easily fixed, often insulting, usually ignorant, occasionally foolish, and frequently wrong.”

Genetically modified food: consternation, confusion, and crack-up

The dissemination of published science to the general public is also heavily politicised. A recent article in JAMA Internal Medicine examined media coverage of scientific articles on technological innovations for early detection of disease, and concluded that “medical media coverage tends to overplay benefits, downplay harms, and ignore conflicts of interest”.

The popular image of the dispassionate scientist beavering away selflessly in his or her lab in order to achieve breakthroughs for the benefit of all humanity is a naive fantasy, promulgated for political purposes. Scientists are human. They personally engage in political activity to advance their own careers and sabotage their rivals, and their work is exploited by both public and private institutions to achieve political ends.

False premise #2: Consensus science exists, and it is an accurate representation of objective reality.

Dahlstrom’s article repeatedly refers to “science misinformation”, without ever defining the term. Reading between the lines, it is obvious that what he means by “misinformation” is information that contradicts the establishment position. As examples of “science misinformation”, Dahlstrom cites “inaccurate information that influences vaccine attitudes and behaviors away from science”, and dissent from “belief in climate change”.

Yet there are many prominent scientists who question the safety and efficacy of individual vaccines, and.or the combination of vaccines in current vaccination schedules.

Is a study demonstrating increased risk of death in African children who received the diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine “science misinformation”, or an attempt to use the scientific method to improve human lives?

When the associate editor of the British Medical Journal and the founder of the Nordic Cochrane Centre (the pre-eminent arbiter of evidence-based medicine) call into question the integrity of the safety and efficacy trials for human papilloma virus vaccines (Gardasil and Cervarix) into question, are they guilty of “science misinformation”, or are they trying to remedy it?

And is not intentionally omitting scientific data in order to shape a narrative on climate change “science misinformation”?

In Dahlstrom’s universe, “scientific truth” is represented by consensus science, and anything outside that consensus constitutes “science misinformation”.

But to reiterate Michael Crichton’s statement on “consensus science”, which I quoted in Part 1,

“The work of science has nothing whatever to do with consensus. Consensus is the business of politics. Science, on the contrary, requires only one investigator who happens to be right, which means that he or she has results that are verifiable by reference to the real world. In science consensus is irrelevant. What is relevant is reproducible results. The greatest scientists in history are great precisely because they broke with the consensus. There is no such thing as consensus science. If it’s consensus, it isn’t science. If it’s science, it isn’t consensus. Period.”

False premise #3: Views upheld by scientific consensus are a valid basis for public policy

Having thrown in his lot with the dubious notion of scientific consensus, Dahlstrom then proceeds to argue that this consensus can and should be translated into public policy. He admits that science merely provides information, rather than prescribing a course of action based on that knowledge, but then elides the distinction between science and politics:

“Scientific knowledge uncovers truth that explains the world, but it can never dictate what individuals or society should do with that knowledge… Assertions that children should follow recommended vaccine schedules; arguments that climate change deserves more attention; even noncontroversial desires to build greater support for science—these are not facts but negotiations of value and therefore fall under the scientific goal of persuasion.”

But persuasion is patently obviously a political goal, not a scientific goal. “Science” is a process for discovering facts; it is entirely disinterested in whether you accept those facts or not, or what you do with them. There cannot possibly be a “scientific goal of persuasion”.

As the executive editor of the British Medical Journal pointed out,

“Politicians often claim to follow the science, but that is a misleading oversimplification. Science is rarely absolute. It rarely applies to every setting or every population. It doesn’t make sense to slavishly follow science or evidence. A better approach is for politicians, the publicly appointed decision makers, to be informed and guided by science when they decide policy for their public. But even that approach retains public and professional trust only if science is available for scrutiny and free of political interference, and if the system is transparent and not compromised by conflicts of interest.”

Covid-19: politicisation, “corruption,” and suppression of science

In an publicity interview, Dahlstrom, was explicit about the intention behind his article, which was essentially to provide an instruction manual for the political and managerial classes to elicit their desired responses from the masses:

“A story about how the COVID-19 vaccine is allowing families to reconnect after months apart is more persuasive and compelling than explaining how the vaccine works and its efficacy, Dahlstrom said.”

Narratives Can Help Science Counter Misinformation on Vaccines

So there you have it. Dahlstrom doesn’t think you’ll take the politically desired action – lining up for your shot – if you’re provided with factual information about it. Based on an analysis of efficacy data for the currently-available products published in The Lancet, he’s probably right:

“Absolute risk reduction (ARR), which is the difference between attack rates with and without a vaccine, considers the whole population. ARRs tend to be ignored because they give a much less impressive effect size than RRRs: 1·3% for the AstraZeneca–Oxford, 1·2% for the Moderna–NIH, 1·2% for the J&J, 0·93% for the Gamaleya, and 0·84% for the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccines.”

COVID-19 vaccine efficacy and effectiveness—the elephant (not) in the room

Read that last part again, slowly. Taking any of the COVID-19 injections currently on the market will reduce your risk of contracting COVID-19 by between 0.84% and 1.3% – and that’s if you live in a region which currently has community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (which neither Australia or New Zealand have).

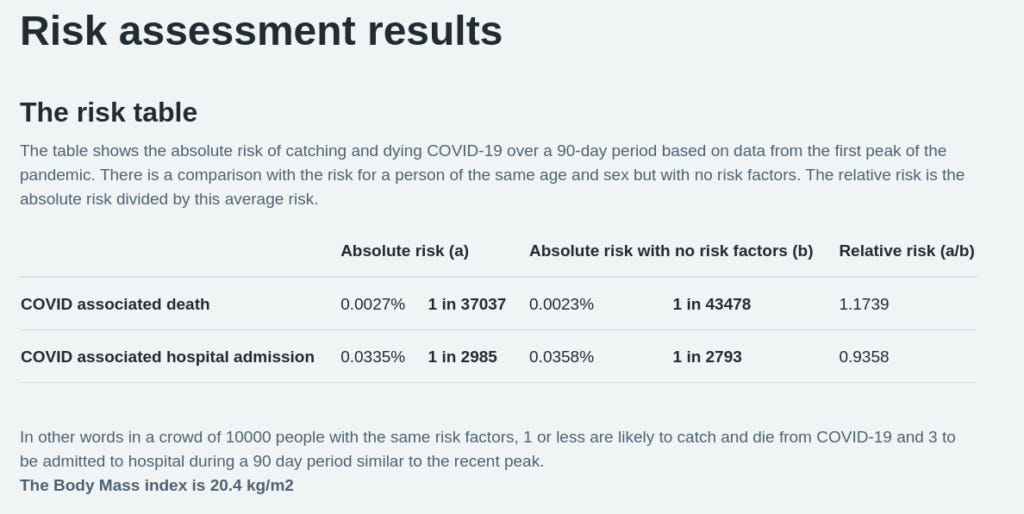

I don’t know about you, but I’m not willing to undertake any risk of adverse reactions to a completely novel technology that has never been deployed on humans before, to reduce the risk of a disease that I would have a 1 in 2793 risk of being hospitalised for, and a 1 in 43478 chance of dying from if I had been living in the UK during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic:

So, to persuade people like me, who have a rational concern for their own well-being and a deep scepticism of the motives of the people and organisations who are so aggressively pushing for my unquestioning compliance, Dahlstrom suggests bombarding us with messages that use an appeal to emotion to bypass our capacity for reason.

Dahlstrom’s thinly-veiled contempt for the capacity of ordinary people to learn how to parse information in order to make better decisions brings to mind the attitudes expressed by the so-called “anti-maskers” who were the subject of the article I discussed in Part 2 of this series. The researchers reported that these citizen scientists “resent what they view as the arrogant self-righteousness of scientific elites”, and in reaction, “assert the value of independence in a society that they believe promotes an overall de-skilling and dumbing-down of the population for the sake of more effective social control.” Quite frankly, it’s hard to disagree with the “anti-maskers'” analysis of our current situation.

To put it plainly, it is Dahlstrom’s view that the masses are too thick to understand facts, so we should roll back millennia of painstaking progress toward the cultivation of our rational capacity, and regress to the age of superstition, emotion-guided decision-making and mindless obedience to whoever asserts authority over us. Just tell the stupid rubes a good enough story and they’ll do whatever you want them to do.

Sorry, Mr Dahlstrom, but I’m not persuaded.