Psychedelics - panacea or psychiatry's new shiny object?

Are psychedelic drugs the solution to the 'mental health crisis', or just the latest manifestation of our 'pill for every ill' delusion?

In a recent episode of the Stand Up Sits Down podcast, I shared my concerns about the resurgent interest in the use of psychedelic drugs for the treatment of various forms of psychological distress (discussion of this topic begins at around 58 minutes).

Before you all bombard me with hate mail and/or stories of your wonderful and life-altering experiences with psychedelics, let me make my position clear. As I stressed in the podcast, I am cautiously optimistic that the use of certain psychedelics may offer substantial benefit to certain people, when administered in the correct set (mindset) and setting (physical and social environment), and followed up with post-trip integration of the psychedelic experiences that is of sufficient duration, and delivered by ethical and skilled individuals.

That's a hell of a lot of preconditions that need to be met for a successful outcome, because there's a hell of a lot that can go wrong. For example:

An ever-increasing number of people are reporting therapy abuse in the context of psychedelics.

I have serious doubts that the conditions for beneficial use of psychedelics can be met by, for example, mail-order at-home ketamine programs (thinly-veiled advertorials for such programs notwithstanding).

I have equally grave concerns about many of the versions of traditional psychedelic rituals that are now promoted to Western 'spiritual tourists', given that these rituals are, in essence, suggestibility techniques for inculcating culturally-sanctioned beliefs:

"Drawing on cross-cultural data analysis, Grob and Dobkin de Rios (1992); Dobkin de Rios and Stachalek (1999), and Dobkin de Rios et al. (2002) have suggested that hallucinogenic substances are used by many indigenous groups to create hypersuggestible states of consciousness, in order to promote fast-paced socialization for religious or pedagogical purposes, as enculturating adolescents during puberty rituals leaded [sic] by elders."

I am deeply suspicious of the motives underlying the aggressive proselytising and marketing of psychedelics by a slew of non-profits, universities, pharmaceutical companies and venture capitalists - including the Australian government's agency for scientific research, CSIRO.

My concerns are only heightened by the CIA's sordid history of use of these mind-altering substances in experiments conducted under the auspices of MK-Ultra, a long-running program of research into mind control.

But the bedrock of my concerns is this: The positioning of psychedelics as therapeutic agents for psychological conditions is just a continuation of the 'pill for every ill' mentality that has resulted in Australia, and other wealthy nations, becoming populations of chronic drug-takers. Consider these alarming statistics:

According to a 2018 Roy Morgan poll, almost 90 per cent of Australians aged over 14 years (93 per cent of women and 85 per cent of men) had taken some form of medication in the last year.

In the same year, when Australia's population stood at 25 180 200, 9 million people were taking at least one prescribed medicine every day, with 8 million taking two or more prescribed medicines in a week, and more than 2 million taking over-the-counter medicine daily.

In 2020-21, the Australian government spent A$13.9 billion on medication subsidised by two schemes - the PBS and RPBS - which jointly underwrite almost all prescribed medicines (and some over-the-counter medicines and non-drug items), accounting for 81 per cent of the cost of PBS and RPBS medicines. This works out to A$541 spent per person. Consumers paid the remaining A$3.2 billion towards their PBS and RPBS prescriptions.

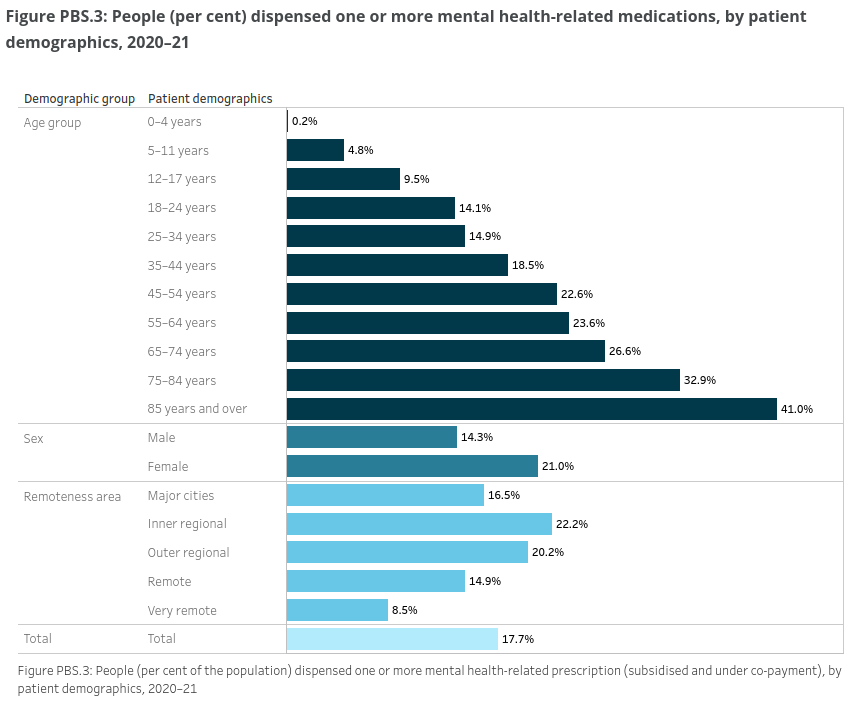

Also in 2020-21, 4.5 million individuals (17.7 per cent of the Australian population) filled a prescription for a 'mental health-related medication', with an average of 9.4 prescriptions per patient; 73.1 per cent of these mental health-related prescriptions filled were for antidepressant medications. Females are one and a half times as likely to be prescribed a 'mental health-related medication' as males, and the percentage of people on such brain-altering drugs rises stepwise with age; an astounding 41 per cent of Australians aged over 85 are on prescription medications for a (purported) mental health condition:

What do we have to show for this profligate spending on pharmaceuticals? We're fatter, sicker and more miserable than ever before.

A sane but naive person would conclude that, if the 'health system' that we have isn't actually delivering healthier, happier people, then it is not working, and those running it should try a different approach.

A cynic, on the other hand, would observe that every system produces exactly the outcomes it was designed to produce. To the pharmaceutical-medical-industrial complex, production of permanently ill, chronically unhappy people is a feature, not a bug.

And so, now that the 'serotonin deficiency'/'biochemical imbalance' hypothesis of depression has been comprehensively debunked, and the much-vaunted serotonin-modulating antidepressants are losing their sheen, the psychedelic-industrial complex is wheeling in the next miracle cure for human misery.

They even have a new version of the neurobabble that was used to sell us on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) as the salves for our suffering. As Dr Joanna Moncrieff (author of the devastating dismantling of the serotonin hypothesis that I referenced in my previous article, Has psychiatry finally reached its Apocalypse Now moment?) crisply observes:

"In an interview published in Nature, psychopharmacologist and psychedelic researcher, David Nutt, suggests that psychedelics ‘turn off parts of the brain that relate to depression’ and ‘reset the brain’s thinking processes’ via their actions on cortical 5-HT2A receptors. Others assert they enhance brain ‘connectivity’. The John Hopkins University website alleges they offer the promise of ‘precision medicine treatments tailored to the specific needs of individual patients’. All these claims are pure speculation."

Forgive me if, like Joanna Moncrieff, I'm a little less than wildly enthusiastic about the latest panacea; I've seen this movie before. No doubt the busy-bee researchers who ploughed gazillions of taxpayer dollars into studies like the one that found that people whose antidepressant prescriptions were guided by pharmacogenomic testing weren't any less likely to be depressed after six months on their super-sciencey-selected drugs than people whose doctors just put them on whatever random happy pill they felt like dishing out that day, will happily pivot to burning up taxpayer dollars on studies that - eventually - find that pharmacogenomically-guided psychedelic prescriptions aren't any more effective than buying a pill from some shady dude at a rave. Because, as Will Hall incisively observes:

"Psychedelics—as weird, unpredictable, mind-shaking and life-altering as they can be—are still the same underground marketed drugs: they intoxicate you, get you high, and you come down."

What I find particularly irritating about the pro-psychedelic neurobabble is that the biological mechanisms by which these potent intoxicating agents are claimed to exert their 'curative' effects on psychological suffering, are also activated by a simple, safe, health-promoting intervention that doesn't put people at risk of therapy abuse or bad trips, and is known to be more effective than either medication or psychotherapy for relieving depression, anxiety and psychological distress. What is this secret wellness weapon, you ask? It's called exercise.

For example, last year Japanese researchers reported that the "rapid and sustained antidepressant-like actions of ketamine" are mediated by increased levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) within the brain. They speculated that IGF-1 signalling in the medial prefrontal cortex of the brain might be crucial to the enhanced neuroplasticity (ability of the brain to rewire itself in response to experience) which is believed to induce the antidepressant effects of ketamine. The press release announcing the study breathlessly forecast a whole new line of drug development arising from this discovery (ka-ching!):

"The link between ketamine and IGF-1 presents a brand-new direction for future studies investigating antidepressants that target IGF-1 directly."

Using Ketamine to Find an Undiscovered Pathway in Depression

Y'know what else raises both IGF-1 and BDNF levels within the brain, and increases neuroplasticity? You guessed it: exercise. Added bonus: exercise does it without causing "dependence, hallucinations, and delusions". But what would be the fun in that? And more to the point, who would turn a profit from it?

A recently-published umbrella review of physical activity interventions found that exercise predictably reduces anxiety, depression and psychological distress, and furthermore, it is about 50 per cent more effective at doing so than either medication or cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

Higher intensity exercise programs of between six and 12 weeks duration were shown to be more effective than lower intensity exercise (such as moderate-paced walking, yoga and Pilates), but all forms of physical activity demonstrated beneficial effects on psychological function.

Furthermore, exercise enhances depressed people's ability to feel happy when good things happen to them - that is, it combats anhedonia, or reduced motivation or ability to experience pleasure, which is a hallmark of depression.

On the other hand, SSRI antidepressants reduce reinforcement sensitivity, causing emotional blunting (reduced ability to feel either happy or sad) in 40-60 per cent of patients taking these drugs.

This reduction in reinforcement sensitivity also causes reduced ability to reach orgasm even in non-depressed people. Sexual dysfunction is a widely-reported and exceptionally distressing adverse effect of SSRIs, which often persists long after people stop taking the drugs.

And of course, exercise has an immense number of positive 'side effects' on many of the pathophysiological hallmarks of depression and anxiety. To name just a few:

Exercise reduces visceral adipose tissue, the deep belly fat that is associated with heightened risk of depression.

Exercise reduces inflammation, while depressed people have elevated levels of inflammatory chemicals both in their brains, and throughout their bodies.

Exercise helps to overcome insulin resistance; insulin resistance is strongly associated with increased risk of developing major depressive disorder.

As mentioned previously, exercise increases secretion of IGF-1 and BDNF, both of which rapidly exert antidepressant effects.

Now, it may turn out that psychedelics are safer and more effective than SSRIs, SNRIs, and all the previous drugs that have been proffered as solutions to the pain of life. They may not cause emotional blunting, or sexual dysfunction, or bone fractures, or terrible withdrawal symptoms (although as Joanna Moncrieff points out, the early promise that psychedelics would 'cure' depression in just one to two sessions has not panned out, with many people converting to long-term users).

But even if they do prove superior to other psychoactive medications, my question will be:

"Are they better than exercise?"

That is, can any drug be more effective at improving mood, enhancing your ability to feel happy, and boosting your sense of self-efficacy, all while making you physically healthier and reducing your need for other pharmaceuticals (such as drugs for high blood pressure, diabetes and high cholesterol), than exercise? Because if it doesn't work better across the board than exercise, then by definition it's an inferior treatment and I would question whether it should be publicly funded.

Whatever the benefits of psychedelics may be, I would take a lot of convincing that, at least in the current economic and social context, they're not feeding into the 'pill for every ill' mentality that has generated our thoroughly dysfunctional not-health-care system.

Think you can change my mind? I'm very open to respectful dialogue on this topic. Please leave your comments below!

Update

In a remarkable stroke of good fortune, the always-excellent Simon Hill published an interview with psychedelic researcher Professor Susan Rossell, just a couple of days after I put out this post. I highly recommend watching it.

Pay particular attention to Rossell’s comment at around 24 minutes, that in one of the major clinical trials that has been touted as demonstrating the huge potential of psychedelics as therapeutic agents, only 5 per cent of patients who were originally screened to enter the trial actually passed all the participation criteria and completed psychedelic therapy. In other words, the vast majority of people were found to have characteristics that ruled them out.

At around 24’50”, Rossell reveals that most of the clinical trials on psychedelic therapy only have three month follow-up periods, and the longest follow-up period is six months.

Furthermore, despite careful screening, in Rossell’s own trials, around 10 per cent of participants have bad trips (she discusses this at around 19’20”), and the long-term implications of this, including the possibility of lasting trauma, are not known.

These drugs are not ready for prime time!

I was very glad to see MKUltra appear in this article. It is so easily ignored or overlooked. That is an avenue of psychological abuse that remains relevant to this day because MKUltra programs *never* ceased. They changed names and became even more secret, entrenched as methodologies of individual and mass mind control utilised by the 13 international occult societies, dozens of military-grade intelligence organisations, and organised crime syndicates. I will write more on it at a later time, but it is truly a soul-taxing topic to research.

Thank you for writing this, so refreshing to read amongst the increasing emergence of the psychedelic fanfare.