Immunity debt: Yet another cost of bad COVID-19 policies

As an unprecedented wave of germaphobia swept the world in 2020, with hand sanitisers (including carcinogenic ones) popping up in every shop, grandparents too terrified to hug their own grandchildren for fear of catching a virus which children rarely contract and almost never spread, and bizarre and nonsensical diktats issued by unelected and accountable bureaucrats (currently in my home state of Queensland you can eat and drink whilst sitting down at a restaurant or bar, but not whilst standing up, and up to 20 people can dance if they’re attending a wedding, but otherwise no dancing permitted… because… well… virus), Australian doctors and the lay public alike noticed something rather interesting: no one seemed to be getting sick.

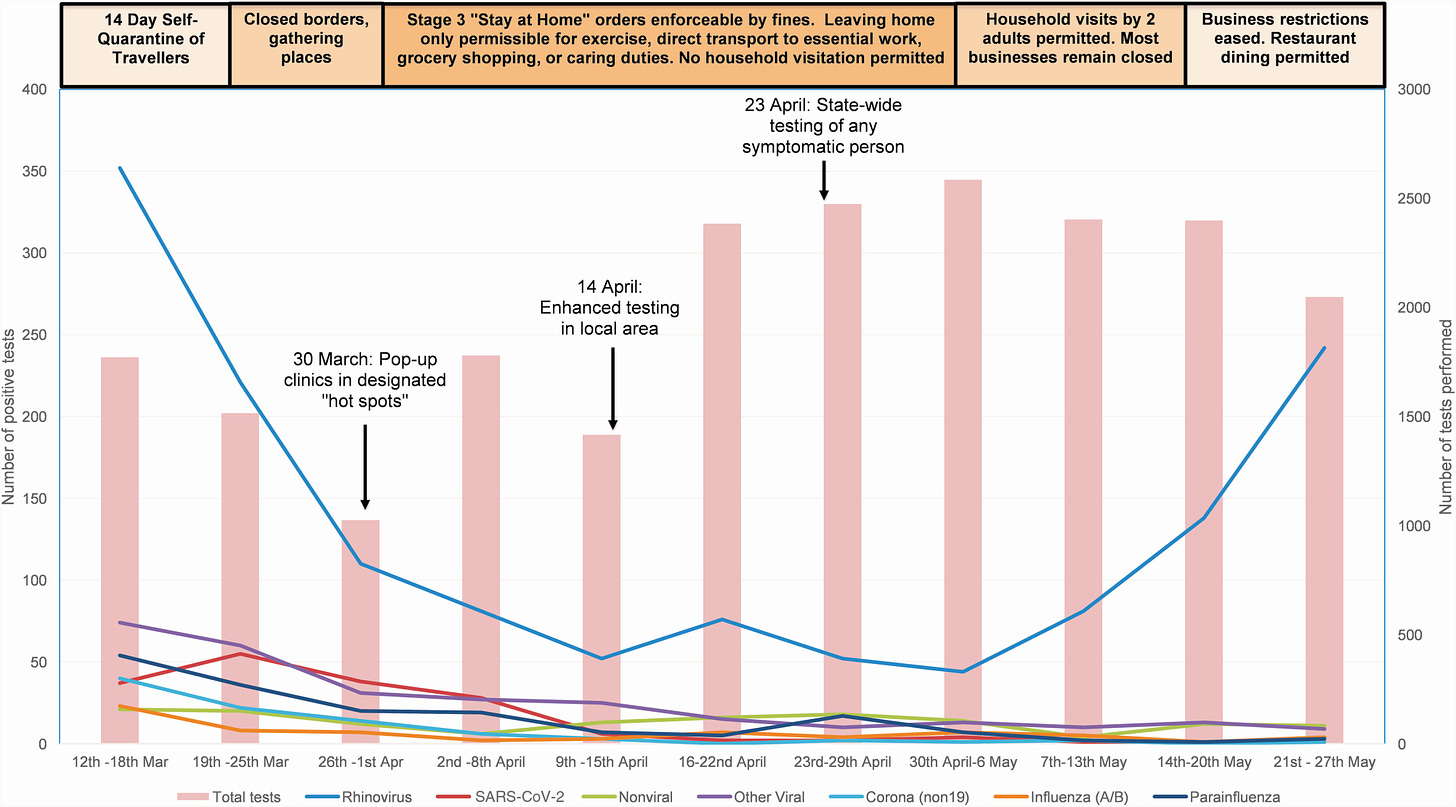

St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney documented a dramatic decline in positive test results for an array of viruses that normally circulate in winter, causing coughs, colds and flu-like illness:

Influenza practically disappeared in Taiwan and Singapore. Notably, influenza virtually vanished from Australia at a time when only Victoria had mandated the wearing of face masks in public, so the mask promoters definitely can’t claim credit for it.

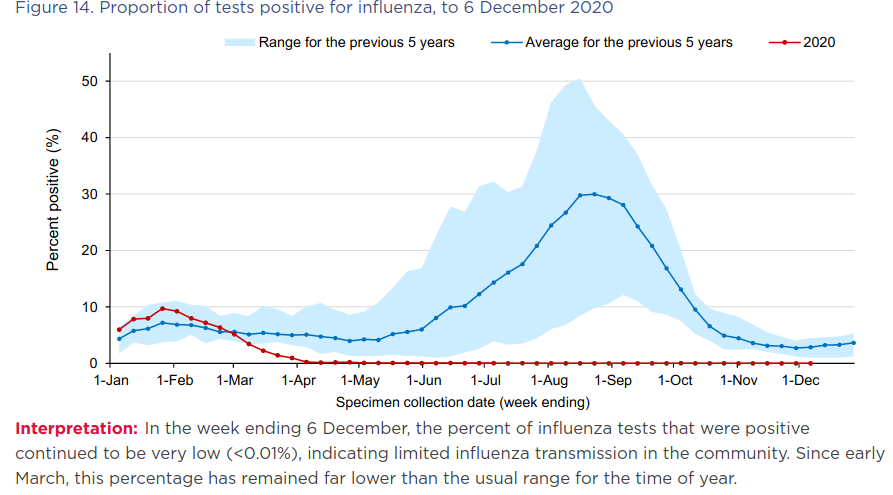

The disappearance of influenza also wasn’t due to a lack of testing; the number of laboratory tests for influenza increased in 2020:

However, the percentage of samples that tested positive for influenza viruses plummeted:

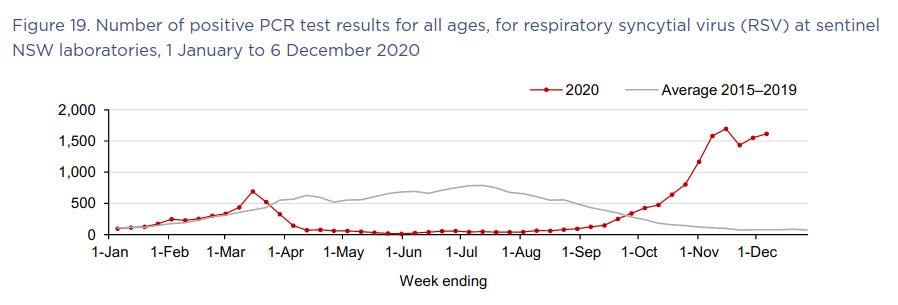

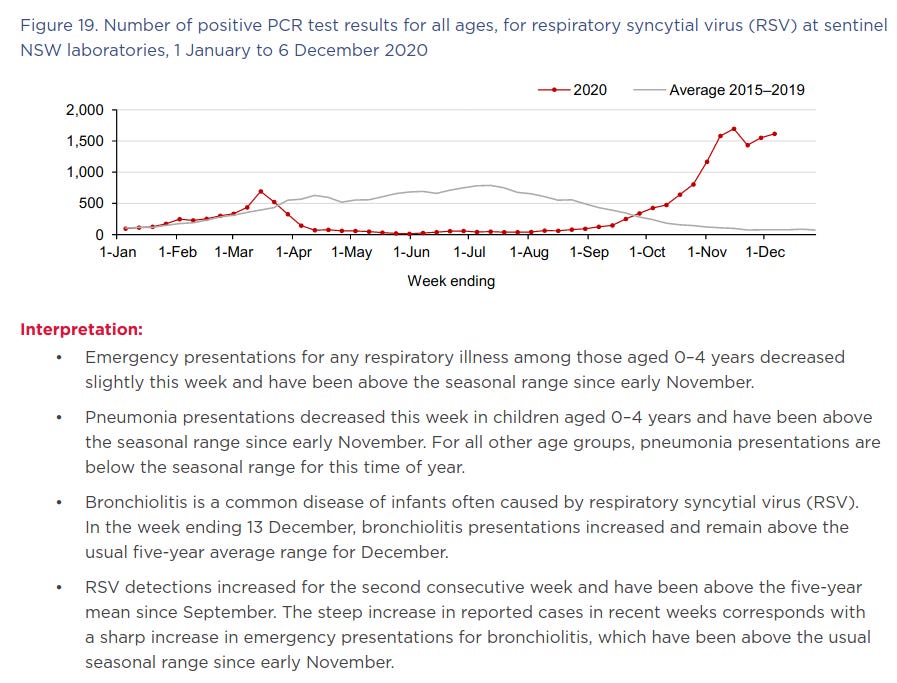

Likewise, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), a common cause of respiratory infections in children, practically disappeared from Australia during the winter season when it normally circulates along with influenza viruses, coronaviruses, rhinoviruses and other lurgies:

The same phenomenon has been documented in the US, UK and France. Chickenpox, measles and rotavirus infections also declined significantly in France.

Given that the low rates of influenza and RSV infections continued after stay at home orders, school closures and other restrictions on freedom of movement were lifted, the most likely explanation for the unusual absence of influenza and RSV viruses during the usual cold and flu season of 2020 is the closing of international and, to a lesser extent, state borders.

New influenza strains arise in east and Southeast Asia each year, and - under normal circumstances of open borders and unfettered travel - globe-trot from their birthplace to Oceania, then on to North America and Europe, before finally becoming extinct in South America. But with trade and travel between Australia and Asia halted, this normal migratory pattern of influenza was interrupted in 2020.

Well, you might be thinking, that’s good news. Isn’t it better that fewer nasty winter bugs were circulating last winter? After all, no one enjoys getting the flu themselves, or having to keep their snotty kids home from school for a week!

Not so fast. After the unprecedented winter lull, RSV infection rates in Australia skyrocketed in spring, shooting far above the levels typically seen in winter, and accompanied by a surge in diagnoses of bronchiolitis, a potentially serious (even fatal) condition which is most commonly caused by RSV:

What happened? According to the French Pediatric Infectious Disease Group (GPIP), the lack of normal immune system stimulation that usually occurs each winter as our immune systems encounter a variety of seasonal viruses, may have resulted in an “immunity debt”. And when that debt is called in, we see a rebound increase in infectious illnesses:

“The longer these periods of ‘viral or bacterial low-exposure’ are, the greater the likelihood of future epidemics. This is due to a growing proportion of ‘susceptible’ people and a declined herd immunity in the population.”

As the GPIP position paper explains, frequent exposure to pathogens (such as bacteria and viruses) trains the innate immune system – the first-responder arm of the immune system – to be more efficient at finding and destroying invaders.

Children generally have greater exposure to pathogens than adults due to mixing in larger groups than most adults, as well as their less-than-stellar personal hygiene habits.

This heightened exposure results in intensive training of their innate immune systems, which primes them for more robust immune responses against commonly-encountered pathogens, such as RSV and influenza viruses:

“The concept of trained immunity corresponds to a kind of long-term functional reprogramming of innate immune cells, stimulated by pathogens and which would lead to a reinforced response during subsequent exposures. This process would have great advantages for host defense. Thus, this trained immunity would be established in children particularly exposed to viral infections in the first years of life and would be more effective in them than later in adulthood.”

However, the ill-thought-through policy responses to COVID-19 deprived children of the normal immune stimulation that occurs when they mix with each other, and consequently encounter novel forms of virus that have hitch-hiked their way into new populations by hanging out in the respiratory tracts of travellers (without necessarily making them sick).

Without their usual intense winter-time training in 2020, children’s immune systems were weakened. When greater opportunities for social contact emerged in the spring, RSV tore through Western Australia and New South Wales, while Victoria, which suffered through the longest and harshest lockdown, along with prolonged school closures, saw a surge of RSV cases in mid to late summer.

The immunity debt caused by the near-absence of influenza in Australia in 2020-21 is also likely to result in an earlier and more severe influenza season when the national border is reopened.

In addition to increased susceptibility to infection, the French authors worry that the lack of immune training caused by nonpharmaceutical interventions to control the spread of SARS-CoV-2 may lead to an increased rate of allergic and autoimmune disease further down the track, congruent with the “hygiene hypothesis”.

The gilded cage that Australian politicians have imprisoned us in for the past 18 months by slamming shut both national and state borders is not just stymieing the economy, keeping families apart and thwarting our wanderlust; it’s backing us into a very dangerous corner.

As renowned University of Oxford epidemiologist Dr Sunetra Gupta has pointed out,

“Yes, international travel facilitates the entrance of contagion, but what it also does is it brings immunity. Why don’t we get flu pandemics anymore? Because before 1918 there was not sufficient international travel or densities of individuals to keep flu on as the sort of seasonal thing it is now. Pockets of non-immune people would build up, and then they would be ravaged. That was the pattern until the end of the First World War. Since then, many of these diseases have become endemic. As a result of which we are much more exposed to diseases in general and related pathogens, so if something new comes along we are much better off than we would be if we hadn’t had some sort of exposure to it. If coronavirus had arrived in a setting where we had no coronavirus exposure before, we might be much worse off.”

We may already have herd immunity – an interview with Professor Sunetra Gupta

Ah, but don’t you worry your pretty little head about such matters, coos the pharmaco-medical-industrial-media complex. There’s a simple solution to this complex problem: just take more vaccines.

The GPIP urges for an expansion of the French national vaccine schedule to try to mitigate the immunity debt, while Ralph Baric, the US scientist whose gain-of-function research almost certainly led to the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus associated with COVID-19), is working on a pancoronavirus vaccine, which he promises will protect you against any future coronaviruses that emerge – including, one hopes, the ones he’s cooking up in his lab.

Just weeks before the first case of COVID-19 was identified in Wuhan, China, the World Health Organisation held the Global Vaccine Safety Summit. One of the speakers was Heidi Larson, director of the Vaccine Confidence Project, which is funded by pharmaceutical companies, the secretive globalist think-tank Chatham House, and a gaggle of not-for-profits, tax-exempt foundations and NGOs with deep ties to Big Pharma.

During her address, Larson made the following, rather disturbing comments (beginning at 1:29:50 in the final video block):

“I think that one of our biggest challenges is… we’re in a unique position in human history, where we’ve shifted the human population to vaccine-induced, to dependency on vaccine-induced immunity… We’re in a very fragile state now. We have developed a world that is dependent on vaccinations.”

Vaccine safety in the next decade: Why we need new modes of trust building?

Let that statement about our “fragile state” sink in for a moment. What Larson is alluding to is that the robust ‘herd immunity’ which in the past was developed through natural infection has been traded in for a much more tenuous - but highly profitable - vaccine-induced immunity.

Natural infection generally renders one immune for life, or at the very least, resistant to serious illness upon reinfection. It is robust and broad-based, conferring protection against variant strains of the bacterium or virus that caused the initial infection, because it engages innate, humoral and cellular immunity.

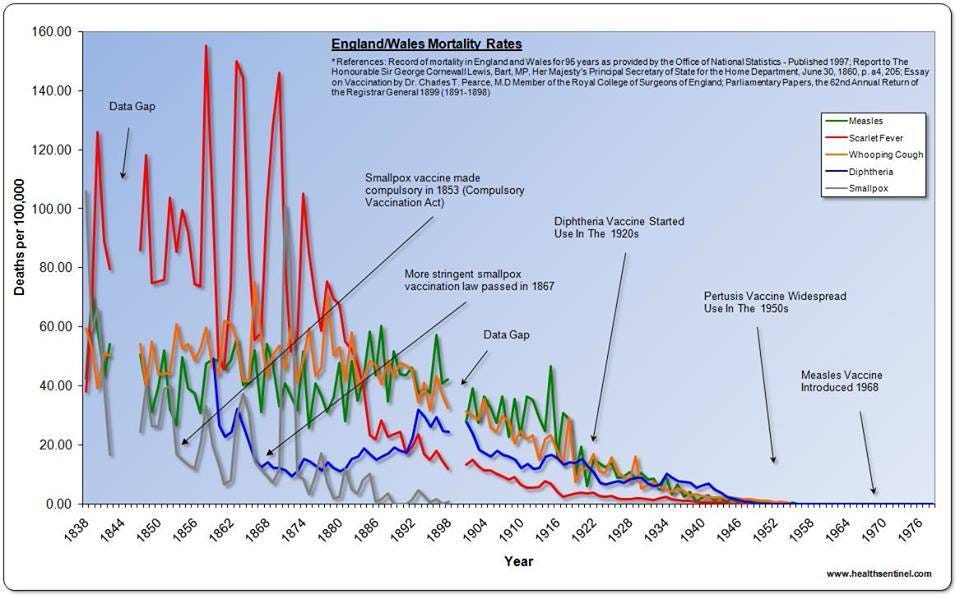

Vulnerable newborns were formerly protected by maternal antibodies, until their immune systems were mature enough to cope with measles, chickenpox and other common infectious diseases of childhood, which had virtually disappeared as causes of mortality by the mid-twentieth century - before vaccines against them were introduced:

But vaccine-induced immunity is far more tenuous. Between 5 and 10% of children fail to mount an immune response to measles vaccine, for example. The problem of waning vaccine-induced antibodies is well-recognised, and has led to the addition of ‘booster’ doses to the recommended vaccine schedule. Vaccination drives the development of variants, which may be more contagious and/or virulent than the strain suppressed by the vaccine.

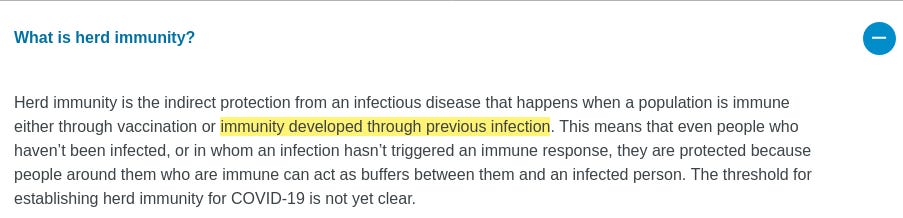

Perhaps in recognition of the “fragile state” that their relentless push to vaccinate the world has helped to create, WHO was caught red-handed last November in an extraordinary attempt to redefine herd immunity. As of early November, their definition of herd immunity read as follows:

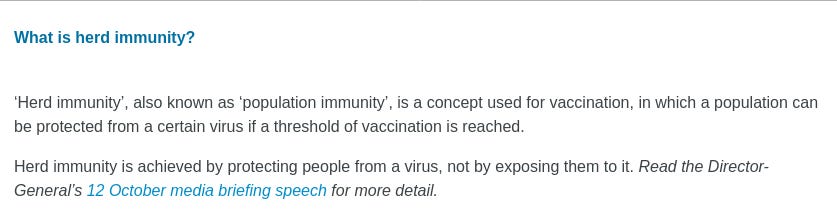

But by mid-November, WHO had attempted to shove the immunologically far-superior naturally-acquired immunity down the memory hole, insisting that only vaccination could confer herd immunity and that the concept itself was an artefact of the vaccine era (a demonstrably false statement, as the term was coined in the 1930s – over three decades before the measles vaccine was introduced - by A. W. Hedrich who meticulously documented the regular cycles of measles outbreaks in Boston and observed that measles all but disappeared when 68% or more of the children had acquired natural infection.

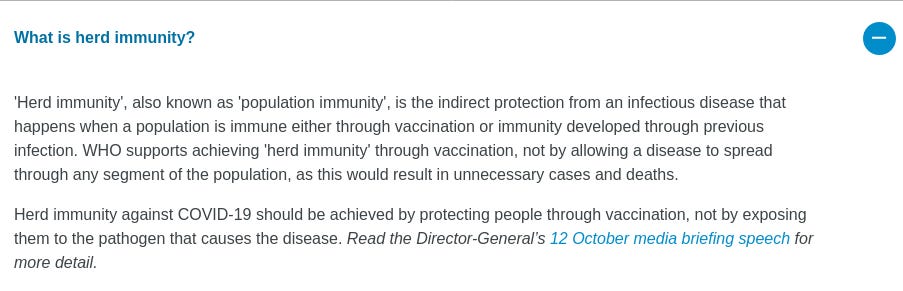

The change did not go unnoticed, and apparently embarrassed by the subsequent outcry, WHO changed the definition back again, throwing in a spurious argument that vaccine-induced immunity to SARS-CoV-2 would be ethically superior to naturally-acquired immunity:

Hopefully by this point you will understand why WHO’s claim that allowing SARS-CoV-2 to spread through the population is more dangerous than injecting every man, woman and child on the planet with experimental gene therapy is utterly false.

In particular, since children show robust innate immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection, and adults living with children aged 11 and under have a decreased risk of dying of COVID-19, it’s highly likely that leaving schools open and allowing healthy children to be exposed to SARS-CoV-2 would have ended the pandemic much sooner and with less suffering and death.

We really are poised on the edge of a precipice. If we continue to adhere to bad policies that lead to the weakening of our immune systems through lack of immune training – especially in our children – we could potentially witness a replay of the decimation of native populations that occurred when they were exposed to infectious diseases that had become endemic among Europeans, but to which they had no previous exposure.

Our grandmothers told us that whatever doesn’t kill us makes us stronger. If we don’t start reclaiming the wisdom of our elders, we might well find that what has made us weaker will end up killing us.