5 reasons to think twice before taking an antidepressant

Up to 10.2 per cent of Australian men and 17 per cent of women take an antidepressant, but a growing chorus of informed voices is asserting that these blockbuster drugs do more harm than good.

A letter published in the BMJ (formerly the British Medical Journal) in December 2023, calling on the UK government to commit to a reversal in the rate of prescribing of antidepressants, prompted me to update and republish this article, which I wrote back in 2013.

The BMJ letter was penned by 31 medical professionals, researchers, patient representatives, and politicians, including two legends in the field of psychiatric reform, Dr James Davies and Dr Joanna Moncrieff, whose work I have referred to in several previous articles (see here, here and here).

Among the many startling facts contained in the letter are these:

Antidepressant prescriptions have almost doubled in England over the past ten years;

Almost 20 per cent of the adult population of England is prescribed an antidepressant within a given year;

Around half of patients taking an antidepressant are now classed as long term users;

Antidepressants have no clinically meaningful benefit beyond placebo for patients with mild to moderate depression; only those with the most severe depression can expect to experience benefit;

Despite this, the majority of UK patients who have been prescribed an antidepressant, report only mild symptoms of depression; in fact, one study found that "58% of people taking antidepressants for more than two years failed to meet criteria for any psychiatric diagnosis".

But here's the real kicker:

"Rising antidepressant prescribing is not associated with an improvement in mental health outcomes at the population level, which, according to some measures, have worsened as antidepressant prescribing has risen."

Read that one more time. As usage of antidepressants has dramatically increased, community mental health has declined. That doesn't prove that taking an antidepressant leads to worse mental health outcomes, of course. But if antidepressants were actually effective, you would at least expect to see some improvement in indicators of psychological well-being, in communities with widespread use.

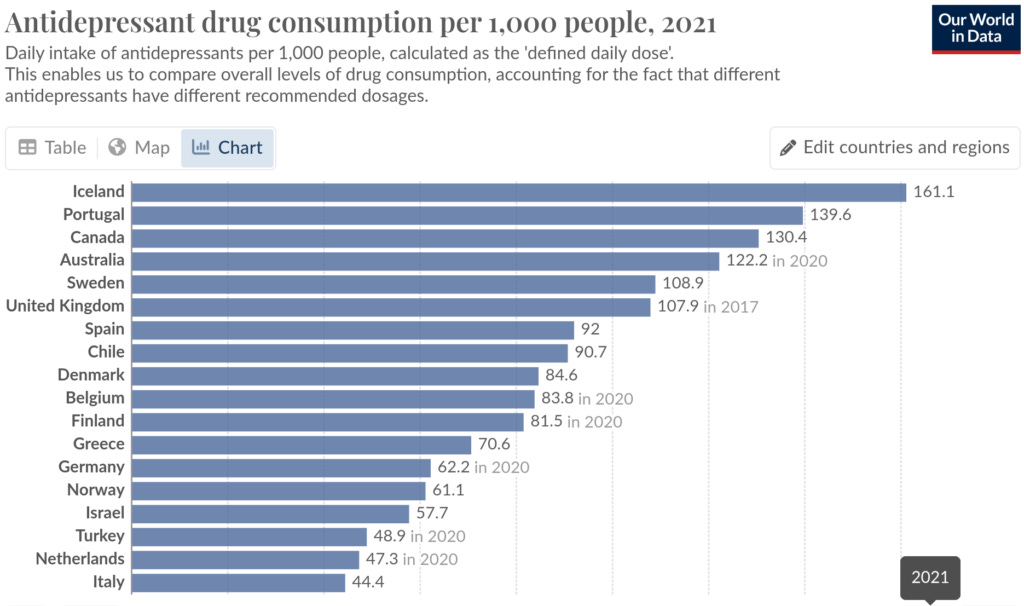

The letter concludes with a call for other countries with high levels of antidepressant prescribing to also commit to lowering prescribing rates. Which countries should heed that call? It turns out that five countries are even heavier users of antidepressants than the UK: Iceland, Portugal, Canada, Australia and Sweden:

Australia's antidepressant bender

Australia has the dubious distinction of having the fourth highest rate of antidepressant consumption in the world. 32.7 million antidepressant prescriptions were dispensed in the 2021–22 financial year, when the population was roughly 25.5 million. In 2021, up to 10.2 per cent of Australian men and 17 per cent of women took an antidepressant. Alarmingly, antidepressant prescriptions to young Australian females - those in the age groups 10-17 and 18-24 - ticked up substantially in the first year of the manufactured COVID crisis:

With that background, let's move onto...

A short history of antidepressants

The class of drugs known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) brought about a revolution in the treatment of depression. Previous classes of antidepressants, such as monoamine oxidase inhibitors and tricyclics, had such severe side effects, and were so easy to overdose on (intentionally or accidentally), that they were reserved for severe cases of depression.

The first SSRI to hit the market was zimelidine (Zelmid), which was released onto the European market by Astra Pharmaceuticals in 1981. Astra's triumph turned out to be short-lived. The new wonder-drug was found to increase the risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome, a potentially life-threatening autoimmune disease which affects the peripheral nerves, by a whopping 25-fold. Zimelidine was withdrawn from the market in 1983.

One would think that zimelidine's spectacular fall from grace would put other drug companies off the whole idea of developing drugs that manipulate serotonin levels. But the American pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly had observed the transient commercial success of zimelidine, and grasped the potential to turn the manifestation of human distress known as 'depression' into a highly lucrative market. Lilly dusted off an SSRI compound that they had first synthesised in 1972, and shelved for lack of any commercial application. That compound was fluoxetine. You know it as Prozac, the first of the blockbuster SSRIs.

Prozac was approved by the FDA in late 1987. Its meteoric rise unleashed a swarm of competitor drugs, including Zoloft, Paxil, Cipramil, Lexapro, Luvox and Celexa. Despite the Zelmid fiasco, SSRIs were claimed to have such a low risk of causing side effects, that they could safely be prescribed even in mild depression. The promise of 'better living through changing your brain chemistry' proved enormously appealing to both the general public and to doctors.

In fact, doctors began diagnosing depression in patients who would previously have been labelled 'nervous' or 'anxious' - and prescribed a sedative such as Valium - and instead prescribing an SSRI to correct the 'chemical imbalance' in their brains that, according to the drug companies, was the underlying cause of their malaise.

But SSRIs are far from harmless 'feel-good' pills, and the science behind their prescription is dubious, at best.

Here are five disturbing facts about SSRIs:

#1. There is no reliable science supporting the theory that depression is due to a biochemical imbalance, and that SSRIs correct that imbalance.

As shocking as it may seem, the entire scientific basis for prescribing SSRIs is built on quicksand. The notion put forward by the drug companies that make SSRIs, and accepted as gospel truth by most GPs, psychiatrists and popular magazines, is that depression is caused by low serotonin levels in the brain, and that SSRIs, by raising serotonin levels, treat the depression at its biochemical root.

But numerous researchers have pointed out that this is pure speculation, with no hard proof.

David Healy, professor of psychiatry at Cardiff University and author of Let Them Eat Prozac, devoted ten years to studying serotonin levels and activity in depressed people. He found next to no evidence to support the idea that they had any abnormality in their serotonin metabolism. He describes the 'chemical imbalance' theory as

"pure 'bio-babble' which has replaced the psychobabble of the Sixties and Seventies."

George Ashcroft, the psychiatrist who first advanced the serotonin theory of depression in the late 1950s, abandoned it due to lack of evidence by the 1970s. He wrote:

"What we believed was that 5-HIAA [i.e. serotonin] levels were probably a measure of functional activity of the systems and not a cause. It could just as well have been that people with depression had low activity in their system and that 5-HIAA was mirroring that” [my emphasis].

In other words, he realised that it was just as likely that our emotions cause changes in neurotransmitter levels, as it was that neurotransmitters such as serotonin governed our emotions.

Consider this: if you you take aspirin for a fever and your body temperature drops, no doctor would argue that the fever was due to an aspirin deficiency! Likewise, the fact that SSRIs raise serotonin levels, and that some people feel better when they take SSRIs, does not prove that these patients had a deficiency of serotonin while they were depressed. In fact, as David Healy categorically states,

"No abnormality of serotonin in depression has ever been demonstrated."

David Healy, Let Them Eat Prozac, p. 12

As I wrote in Has psychiatry finally reached its Apocalypse Now moment?, the 'chemical imbalance' theory of depression was finally, categorically consigned to the dustbin of history in 2022, when a comprehensive systematic umbrella review co-authored by Joanna Moncrieff concluded that "there is no convincing evidence that depression is caused by serotonin abnormalities, particularly by lower levels or reduced activity of serotonin."

#2. SSRIs are no more effective than placebo, and their effect on severely depressed patients is clinically insignificant.

Numerous studies have found that SSRI antidepressants don't relieve mild to moderate depression any better than placebo (an inactive 'dummy pill'), but it had long been thought that they offer significant benefits to severely depressed patients.

However, even this benefit is increasingly being called into question.

A 2008 meta-analysis combined data from all 47 clinical trials submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a precondition for the licensing of four SSRI antidepressants, including unpublished trial data.

(Bear in mind that "Studies which show no effect have a tendency to be 'filed' rather than being submitted for publication".)

What the researchers found was that the response to placebo duplicated more than 80 per cent of the improvement observed in those who were taking antidepressant drugs.

When participants were differentiated based on the severity of their depression at the beginning of the trial, the researchers found

"virtually no difference in the improvement scores for drug and placebo in patients with moderate depression and only a small and clinically insignificant difference among patients with very severe depression."

In those with very severe depression, the average difference between the effects of the drug and those of the placebo was 1.80 on the Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression (HRSC).

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence specifies a 3 point drug–placebo gap for clinical significance. In other words, if the difference between a treatment and a placebo is less than 3 points on the HRSC, the treatment is unlikely to make a genuine, palpable, positive difference in the daily life of depressed people.

(Side note: other researchers have found that a difference of 3 points on the HRSC is not even detectable by clinicians; a difference of 7 points is required to correspond to a rating of 'minimal improvement'.)

But even this tiny and clinically insignificant difference in response to placebo vs drug in very severely depressed patients, was due more to the fact that such patients are less responsive to placebo than mildly to moderately depressed individuals, than that they respond better to antidepressants.

The authors concluded,

"There is little reason to prescribe new-generation antidepressant medications to any but the most severely depressed patients unless alternative treatments have been ineffective."

As an aside, my clinical experience is in line with the BMJ letter authors' observation that most Brits who are prescribed antidepressants, are either mildly depressed or not depressed at all. The vast majority of my clients who have been prescribed antidepressants would not meet the diagnostic criteria for even mild to moderate depression, let alone severe depression.

One of my clients was even prescribed an SSRI when her dog died, "just in case she had trouble coping". This type of knee-jerk prescribing is deeply irresponsible and utterly without scientific merit, especially with Point #3 in mind.

A systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis published in 2017 included data from 131 randomised placebo-controlled trials enrolling a total of 27 422 participants.

The conclusion is sobering:

"SSRIs did not have a clinically meaningful effect on depressive symptoms. Furthermore... SSRIs significantly increase the risk of both serious and non-serious adverse events."

The authors go on to make these remarks, which I find quite chilling:

"We now believe that there is valid evidence for a public concern regarding the effects of SSRIs [because] antidepressants seem to do more harm than good... We have clearly shown that SSRIs significantly increase the risks of both serious and several non-serious adverse events. The observed harmful effects seem to outweigh the potential small beneficial clinical effects of SSRIs, if they exist."

Let's now take a closer look at some of those adverse effects.

#3. SSRIs cause side-effects that are indistinguishable from the symptoms of depression itself, as well as a host of other unpleasant side-effects.

The authors of the 2017 study mentioned in point #2 present the adverse effects reported in clinical trials of SSRIs in terms of number needed to harm (NNH). An NNH of 20 indicates that for every 20 people taking the drug, one will suffer the specific adverse effect. Here are some of the adverse effects reported, with the NNH after the colon:

Somnolence (excessive sleepiness): 13

Asthenia (a feeling of weakness): 18

Fatigue: 27

Insomnia: 19

Sexual dysfunction: 11

Decreased libido: 24

Nervousness: 19

Agitation: 19

Tremor: 16

Nausea: 9

Diarrhoea: 19

Constipation: 29

Dizziness: 33

Blurred/abnormal vision or dry eyes: 37

Headache: 31

Lightheadedness/faint feeling: 19

Unpleasant taste: 11

Depression aggravated: 82

Chest discomfort: 21

Weight loss: 34

Appetite decreased: 22

Bizarrely, many of these adverse effects are diagnostic criteria for depression itself. Prescribing a drug that frequently causes the symptoms of the condition for which it is prescribed, seems just a tad illogical!

The occurrence of sexual dysfunction in one out of every 11 people who take an SSRI, even in the tightly-controlled environment of clinical trials (which recruit so-called 'perfect patients' who aren't suffering from any other medical conditions at the time of enrolment) is, quite frankly, terrifying.

SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction includes decreased sexual desire, decreased sexual excitement, diminished or delayed orgasm, and problems with erection and ejaculation.

These symptoms may not resolve even after stopping the medication and have been reported by patients to have triggered relationship breakdown and impaired quality of life. Can you think of any crueller punishment to inflict on a person who is already struggling with depressed mood?

Other serious adverse affects of SSRIs that were not detected in the clinical trials due to their short duration and relatively small number of subjects, include an increased risk of bone fractures, violent and even homicidal behaviour, and premature death. (See Anti-depressants increase your risk of bone fracture and Dying to feel better.)

#4. The diagnosis of depression is highly subjective; you may well not 'have depression' at all.

The term 'disease mongering' was coined by the journalist Lynn Payer to describe the process by which those who sell and deliver treatments (including drug companies and doctors) widen the diagnostic boundaries of illnesses, or simply invent diseases to match the treatments they have developed, and then market awareness of these diseases to the 'worried well'.

As David Healy points out,

"Depression was all but unrecognized before the antidepressants; only about fifty to one hundred people per million were thought to suffer from what was then melancholia. Current estimates put that figure at one hundred thousand affected people per million. This is a thousandfold increase, despite the availability of treatments supposed to cure this terrible affliction."

David Healy, Let them Eat Prozac, p. 2

Psychotherapist, writer and former depression patient Gary Greenberg, in his book Manufacturing Depression, humorously describes the diagnostic criteria for depression in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) - the reference used by doctors and therapists to diagnose mental conditions including depression - as a Chinese restaurant menu: choose 3 symptoms from List A, 1 from List B, and 2 from List C, et voilà! - you have a diagnosis of depression.

But all of these symptoms - such as depressed or irritable mood, diminished interest or loss of pleasure in activities one normally enjoys, sleep disturbance, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness, diminished ability to think or concentrate, indecisiveness - are experiences that any person is likely to have at various points throughout their life, as they face challenges, setbacks, life changes, grief and loss.

Our emotions are guidance systems for navigating life as a human, which is, quite simply, a messy and complicated business.

Human psychological suffering is real; the “increasing medicalisation of normal human behaviour”, as psychiatrist and founder of the Black Dog Institute, Gordon Parker, describes it, is bogus. It's the apotheosis of disease mongering.

#5. Taking SSRI and SNRI antidepressants during pregnancy may harm your unborn baby and make him or her more prone to depression and anxiety in later life.

SSRIs are frequently prescribed to pregnant women, particularly those with a history of postnatal depression or depression prior to becoming pregnant, because untreated depression in the mother is not only bad for her, but can also slow down her baby's growth.

But a study of nearly 7700 women found that the babies of women who used SSRIs during pregnancy had a two times greater reduction in head growth than babies of untreated depressed women, even though the women on SSRIs had less depressive symptoms.

Furthermore, babies of women who took SSRIs were more than twice as likely to be born prematurely. Both retardation of head growth and premature birth have serious and potentially lifelong implications for the health and wellbeing of babies.

Babies whose mothers took SSRIs during pregnancy have also been found to have abnormalities in two parts of the brain, known as the amygdala and insula, which are regions critical to emotional processing. Abnormalities in amygdala-insula circuitry have been linked to a higher risk of developing anxiety and depression, especially as children enter puberty.

And a case-control study of 30 630 mothers of infants with birth defects and 11 478 control mothers found that the use of several types of antidepressants in early pregnancy increases the risk of a range of birth defects, including congenital heart defects, diaphragmatic hernia, and two neural tube defects - anencephaly and craniorachischisis - that invariably result in the death of the baby, either in utero or soon after birth.

Even after making statistical adjustments for potential confounders including the mothers' education level, ethnicity, smoking and alcohol consumption and the severity of their depression, strong associations were found between the use of several different types of antidepressants and serious birth defects.

For example:

Use of fluoxetine (Prozac, Sarafem) in early pregnancy more than doubled the risk of coarctation of the aorta, a narrowing of the large blood vessel that carries oxygenated blood out of the heart; and raised the odds of oesophageal atresia (failure of the food pipe to connect with the stomach) by 2.61 times.

Citalopram (Celexa) increased the odds of atrioventricular septal defect ('hole in the heart') by 3.73 times and diaphragmatic hernia by 5.11 times.

Sertraline (Zoloft) was associated with 2.72 times the odds of diaphragmatic hernia.

Paroxetine (Paxil, Seroxat) increased the odds of anencephaly and craniorachischisis by 3.43 times, gastroschisis (protrusion of the baby's intestines, and sometimes the stomach and liver, outside the body through a hole beside the belly button) by 2.11 times

Venlafaxine (Efexor) was associated with a shocking 9.14 times the odds of anencephaly and craniorachischisis - again, serious neural tube defects that are incompatible with life.

Bupropion (Wellbutrin, Zyban) increased the odds of diaphragmatic hernia by 6.50.

It's hard to imagine a crueller punishment to inflict on a depressed woman than the death or serious illness of her baby. Pregnant women who are struggling with mental health conditions, and their unborn babies, deserve better than these ineffective and dangerous drugs.

The bottom line

There are proven, safe and effective treatments for depressed mood that enhance your overall health and well-being. And unlike SSRIs and other antidepressants, which increase the risk of relapsing back into depression once it resolves, Lifestyle Medicine interventions such as physical activity, improved nutrition and effective psychotherapy that equips people with emotional and cognitive coping skills, decrease relapse rates.

Important note: if you are currently taking antidepressants, you should not abruptly stop taking them, as a 'discontinuation/withdrawal syndrome' may occur, including symptoms such as dizziness, electric shock-like sensations, sweating, nausea, insomnia, tremor, confusion, nightmares, and vertigo, as well as a return of the depression symptoms. As described in Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome: An underrecognised and rapidly escalating problem, gradual withdrawal under the supervision of a knowledgable doctor is required, and the drug taper should only be commenced after implementing the diet and lifestyle changes listed in that article.

Read A reader’s response to ‘5 reasons to think twice before taking an antidepressant’.

Finally, I put many hours into writing these posts. If you feel you are getting value from reading my work, please consider a paid subscription:

Thank you for ringing the alarm bells to the harms of this class of drugs. Your work is amazing! I am grateful for your diligence to research and share, helping us to live healthier lives.